Away to the north of Nyanga, in Zimbabwe, at the base of the range of mountains that forms its eastern wall, there was, once, an isolated group of farms. In a gesture which seemed quite out of character for a man who had never shown much sympathy for the Boer cause – and had, indeed, gone out of his way to thwart their political ambitions – they had been granted to a small party of Afrikaner farmers by the arch-imperialist, Cecil John Rhodes, himself.

In recognition of this fact, the dirt road that ran through the middle of them was known, in years gone by, as “The Old Dutch Settlement Road”.

Although seldom visited by all the tourists who like to holiday in the more temperate Nyanga uplands (many staying at Rhodes’ old estate), it is an area I used to know well because it was here we had once farmed too.

When we arrived in the district, back in the 1950s, there was only one surviving remnant of this original group – Gert “Old Man” Mienie who farmed at Cream of Tartar Kops. A jovial giant of a man with twinkling eyes and invariably dressed in stained khaki, he had worked as a transport rider before ending up in Nyanga North where he grew mealies and farmed cattle.

Long before it became fashionable to do so Gert Mienie lived totally off the grid. He had a house generator that operated off a Pelton wheel with buckets on a water furrow. His wife made soap and candles from the fat stored in the tails of their Blackhead Persian sheep. They never bought medicines either, preferring to manufacture their own concoctions which they used to treat both man and beast.

He also had his own brandy still while his old ox-wagon remained parked around the back.

Although the rest of these pioneering farmers had either long since left or died, their presence still lingered on in the names of many of the properties – Witte Kopjes, Groenfontein, Summershoek, Doornhoek, Flaknek etc. Mount Pleasant, the farm to our immediate south, on which there stood the remains of some crumbling tobacco barns, was still referred to, in our day, as Bekker’s Place.

If you hunted around you could occasionally stumble upon the remains of their old homes (there was one on Witte Koppies, for example, which had been built out of white quartz quarried from the nearby hill) and even the odd graveyard. The two young Oosthuizen children who lay buried on our farm had both died of Black-water Fever back in the early 1900s, a common cause of death in those days.

There was something quite sepulchral about the mountain-fringed valley in which they had chosen to live. Maybe it had something to do with all the old ruins, perhaps it was the mountains themselves, with their constantly changing moods, but there seemed to be a presence here, a spirit. I sometimes felt I was walking among ghosts I could never see.

I had some idea who they belonged too. The original Afrikaners who had settled here, courtesy of Mr CJ Rhodes, had not been the first cultivators of this land to have suddenly packed up and left without explanation.

There had been others before them.

The whole country from the Nyanga uplands, north to the Ruenya River and westwards to the Nyangombe River, was strewn with relics from their stay – dozens and dozens of loopholed stone forts, look-out points, pit structures, furnace sites, grinding stones, monoliths and miles of terracing stretching along the mountain sides; the latter were often irrigated by means of furrows that carried water long distances from the streams.

The amount of rock that had been moved to build all this was astonishing although, as Herculean as their labours had been, the stone fortifications tended to suggest that the ordinary villagers had lived in constant fear of attack. Clambering over the piles of rocks I had, in my youth, always imagined some fabulous Rider Haggard vision of lost mines and lost worlds but the sad reality is that the people were probably desperately poor (in his book The Shona and Zimbabwe 900-1850, the academic D.N.Beach describes it as a “culture of losers”. That is as maybe but they certainly appear to have been very hard-working ones!), because the soils they had cultivated were, for the most part, thin and infertile – although they probably supplemented them with kraal manure.

Our farm was no exception. From beacon to beacon it, too, was covered in a jumbled mass of ruins. Exploring them, I was seized by a kind of incredulity. It was impossible not to marvel at the intensity of the endeavour that went in to their construction.

And where had all that passion and effort gone? That was the mystery for me.

One of the aspects of this now abandoned civilisation which especially intrigued me were the endless piles of gathered stones that lay scattered all over the veld. What was their purpose? Why all the effort for so seemingly pointless a task? Again I was flummoxed.

To me, the ruins seemed very old – none of the local tribes people we spoke to appeared to know much about who had constructed them – yet the consensus amongst the experts is that they were mostly built between the 16th and 19th Century by the Tonga people from Zambezi. Adding to the air of mystery, no one seems to be able to state with any degree of certainty why the whole complex was eventually abandoned.

Our own sojourn in this hot, dry, haunted valley came to an end during the Rhodesian Bush War. Remote, cut-off and situated close to the Mozambique border, our farm became an obvious target for the incoming liberation forces. Our only two neighbours were killed, the roads regularly mined, the few cattle we had which had survived drought and disease were rustled and we were eventually forced to move, our farm becoming part of, in the military parlance of the day, a “frozen” area.

It was twenty-years after the war ended before I got to go back to the farm again, only it was no longer a farm. In the interim it had become a black resettlement area.

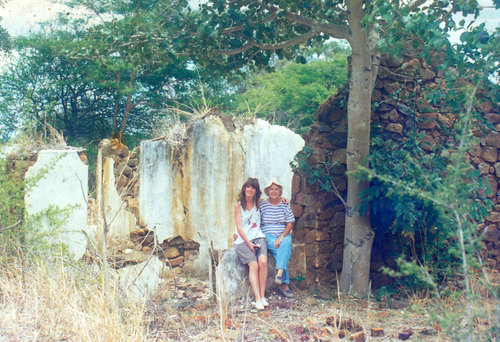

There was not much left to remind me of the years we had spent there. Time – and the war – had taken its toll. Of our old house little remained. At the one end, where the lounge had been, the old fireplace still stood; elsewhere our former home, once so full of life, had been reduced to the cement squares and oblongs that marked our vanished rooms.

Here and there bits of the old wall survived but it no longer supported the roof which had completely vanished. Of my mother’s once extensive garden there was no trace other than one lone bougainvillea which still clung stubbornly to the hillside.

Everywhere else wild nature had come back and reclaimed its own.

As I wandered around looking at all the places that had once meant so much too me I could not help but reflect on the transitory nature of things. As a young boy I had been intrigued by the ancient ruins that lay scattered across the farm; now our old house had joined them.

I found myself thinking about those early Afrikaner settlers too. Like us, they had arrived here, full of innocent optimism and hope that they could create a future and yet few if any of the families had stayed beyond one generation. Now, all that remained of their hard work and industry were a few old bricks, stones and mortar and the occasional gum tree.

The same had happened to us.

What hadn’t altered were the mountains themselves. It is difficult to capture in words the feelings they engendered in me. Looking at them I realised it did not make any real difference what we did. They would live on without us, watching the next generation grow up in a place we had once called home. We had only been there for a few moments and all that mattered was that we had cherished the place and made the most of the time we had had there.

As I pulled over, onto the edge of the road, for one final look back, I realised it was not so much the fact that I had come back but rather that the farm had never left me.

FOOTNOTE:

For the sake of convenience the extensive Nyanga ruin system is often separated in to the Upland and Lowland Cultures. Because our farm lay in the Nyanga valley, the ruins on our farm obviously fell in the latter category.

Below are a selection of photographs showing examples of both types of ruin.

A special thanks to my brother, Paul Stidolph, for providing many of the old black and white pics. A semi-retired farmer still living in Zimbabwe, Paul has conducted an enormous amount of research of his own in to the early history of the country and unearthed a great deal of fascinating material on both its ruins and ancient mine-workings.

Stone fort on old farm. Picture courtesy of Paul Stidolph.

Terracing on old farm. Picture courtesy of Paul Stidolph.

Aerial view of hill-top fort with terracing on old farm. Picture courtesy of Paul Stidolph.

Altar? Near old farm. Picture courtesy of Paul Stidolph.

Pots on Mt Muozi, old farm. Picture courtesy of Paul Stidolph.

Engraved stone. Old farm. Picture courtesy of Paul Stidolph.

Nyahokwe Ruins.

Nyahokwe Ruins. Note stone circle in mid-ground with monolith.

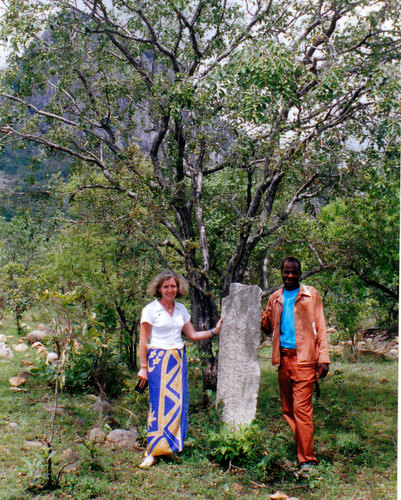

Sister, Penny, with William Kadzima, curator of local museum, Ziwa. Note chipped off section on top left corner of monolith, a common feature of them. This pic was taken on a return visit to area.

Ziwa Ruins.

Ziwa Ruins.

Stone fort with entrance, Ziwa Ruins.

Young self entering pit structure. Nyanga uplands culture.

Nyangwe fort near Mare Dam (Nyanga uplands culture).