I am heading south, from my home at Curry’s Post, in the cool, misty KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, towards the eastern Karoo. I am a man on a mission, in search of stimulating scenes and artistic inspiration. I am confident I’ll find what I seek down there.

It is a journey I have made many times but the suddenness of the change in the countryside always surprises me. You cross over the border and the pine plantations and green pastures of KZN disappear out of sight in the rearview mirror. The rivers are fewer, the trees become small, stunted and windswept, and the veld is dry, earthy and dotted with grey scrub, cactus-like plants, aloes and succulents. It is an enormous, dramatic landscape that completely dwarfs you and makes you feel very small. Vast sun-baked, plains stretch out on either side, blue mountains shimmer in the midday heat; krantzes, kloofs and flat-topped kopjes dance by. The dorps and settlements get smaller, the traffic lighter, and there is less and less sign of human occupation.

As you drive, you are constantly aware of the vast horizons and the space between them and you.`It is strange to think this area was once a vast lake inhabited by giant reptiles, who left their bones behind for palaeontologists to puzzle over millions of years later.

The deeper I penetrate, the more the Karoo begins to work its magic. There is something about this empty, quiet, timeless landscape that eats into my soul. Although it is very different to the country I grew up in, I still feel an instinctive connection with the dry Karoo. Maybe it is because it feels so ancient and exudes such an air of mystery. Like the sedimentary rocks that dominate much of its geology, layers and layers of history lie embedded here, dating back to the beginning of time. If you choose the right spot, you can find yourself looking at more or less the same scene someone thousands of years ago would have seen. Perhaps this gives the Karoo its unique atmosphere, the sense that you are moving amongst ancient spirits. Plus, that huge blue-domed sky which dominates everything and the slightly ethereal quality of the light.

I drive on through a dry, rocky, mountainous country. Hills lead to more hills, the road rises and drops and rises again. The sun is shining straight on the windscreen. The occasional farm roads, grey and rutted, branch off the main road I’m on. I call it a main road but there is so little traffic it is almost a ghost road. Travelling down these side roads the clouds of dust you are kicking up behind you mix with the medicinal-like smell of the plants that grow on the stony slopes.

It is like travelling back in time, you still get a glimpse of what life must have been like centuries ago, back in the days of the trekboers and the travellers, farmers and townsfolk. And before that Khoekoi and San whose demise is one of the great tragedies of Africa.

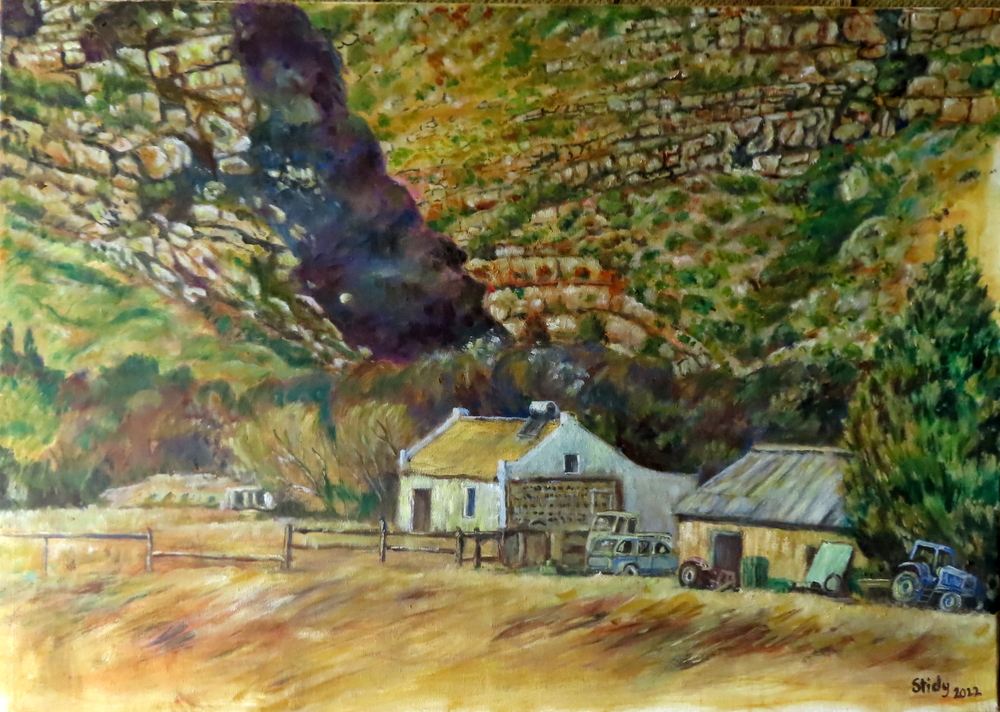

Every now and again a lonely farmhouse swims into view. Most of these old homesteads follow a fairly simple structure with a few outbuildings scattered around the back. Usually, there is a clanking windmill, a cement reservoir in which life-preserving water is stored, a few fruit trees, some drystone enclosures, a sheep kraal, possibly a chicken coop and a collection of labourers cottages situated some distance away. Often there is a graveyard where generations of the same family lie buried.

The farmhouse has always occupied an iconic place in white South African mythology (especially Afrikaner). Wanting land they could call their own, many of the early Dutch settlers, believing it was God’s will that they should do so, packed up their possessions and pushed on deeper and deeper into the interior. If conquest was their questionable motive, they were still, undoubtedly, courageous. Trekking across the dry wasteland, under a burning sun, in their creaking wagons and spans of puffing oxen, they would come to be seen by their descendants, as heroic figures, tough and resourceful, pioneering individualists who helped forge a new nation, giving it an identity rooted in the soil. As each farm was pegged out, it became a further outreach of civilisation, another step in the taming of the land, a further extension of the frontier and of European domination and influence – not that such a harsh environment could ever be truly mastered or contained. The elements always had the final say.

Nevertheless, their love affair with the country and its wild landscape had begun. Perhaps not too surprisingly, the stark beauty of the Eastern Cape has evoked a lot of literary (and artistic) responses (to get some idea of how influential it has been see The Literary Guide to the Eastern Cape: Places and the Voices of Writers by Jeanette Eve). The Cradock area, just up the road, for example, provided the backdrop to one of South Africa’s first and greatest novels – Olive Schreiner’s classic The Story of an African Farm.

It was not always so empty here. From the number of abandoned farmhouses I see on my journey, I can tell a lot of these areas once supported bigger (white) populations than they do now. Poor soils, years of unremitting drought, isolation, poverty, the extremes of temperature, and changing social and economic circumstances – all have taken their toll on the farming community. Other farms have been amalgamated and turned into larger wildlife ranches, partly restoring the land to the way it once was, except there is still a profit motive behind it.

Nowadays, a new factor has come into play. The political winds have changed and are now blowing in the opposite direction. With white ownership of the land becoming increasingly tenuous under the post-apartheid government there has been a steady migration away from the land generations of farmers once assumed was their birthright. With the passing years there will, no doubt, be fewer and fewer of them.

Maybe that is why I feel this compulsion to try and capture on canvas the unique feel of some of these lizard-haunted old buildings before they melt back into the ground from which they were created. Irrespective of how you see the past, they are part of it, a memorial to a particular time in South Africa’s history, now fast fading. What also impresses me, from an artist’s point of view, is how harmoniously these old houses blend into their backgrounds and become part of the land. They have character. They have souls. They have paid their dues. In this respect, they differ greatly from much of our ugly, intrusive, modern architecture.

Rounding a sharp corner, I spot a solitary homestead which fits my artistic needs perfectly. I pull over onto the side of the road and step out to take a few photographs of it. Like a deserted ship marooned in a vast ocean of rock, there is a melancholy, a haunting sadness about it as it stands alone and neglected, completely dwarfed by a huge slab of mountainside behind it. I find myself wondering about who its owners were and what drove them to carve out a life in such an isolated spot? And why did they leave? Even though it is no longer physically inhabited you can still feel their shadowy presence. Once there was life here, it housed not only people but hopes and dreams. Now, it stands deserted and empty, a humbling reminder of life’s impermanence and time’s inexorable march.

Having, for the sake of my painting, tried to absorb as much of the spirit of the place (the genii loci) as possible in such a ridiculously short time, I jump back into the car and drive down the winding road. As the car’s wheels crunch along the gravel, I find my mind drifting back to the farm (subsequently part of a black resettlement scheme) I was raised on, in Nyanga North, in Zimbabwe’s Eastern Highlands. It was also situated in a stunningly beautiful part of the world. It, too, imprinted itself on my youthful mind and remains forever locked in my heart. It was here my obsession with mountainscapes and remote places began.

It is never easy to leave a place, a home with its familiar sights and sounds, its rhythms and associations, its flowers and trees, its birds and animals, its daily routines. Sometimes, however, one has no choice but to love and let go. Although one is physically no longer present it is never a complete break. Every person takes their experiences and memories away with them, They lodge themselves in our psyche, become part of who we are, and affect the way we see and understand the world.

One’s love of the land can also find expression in paintings…