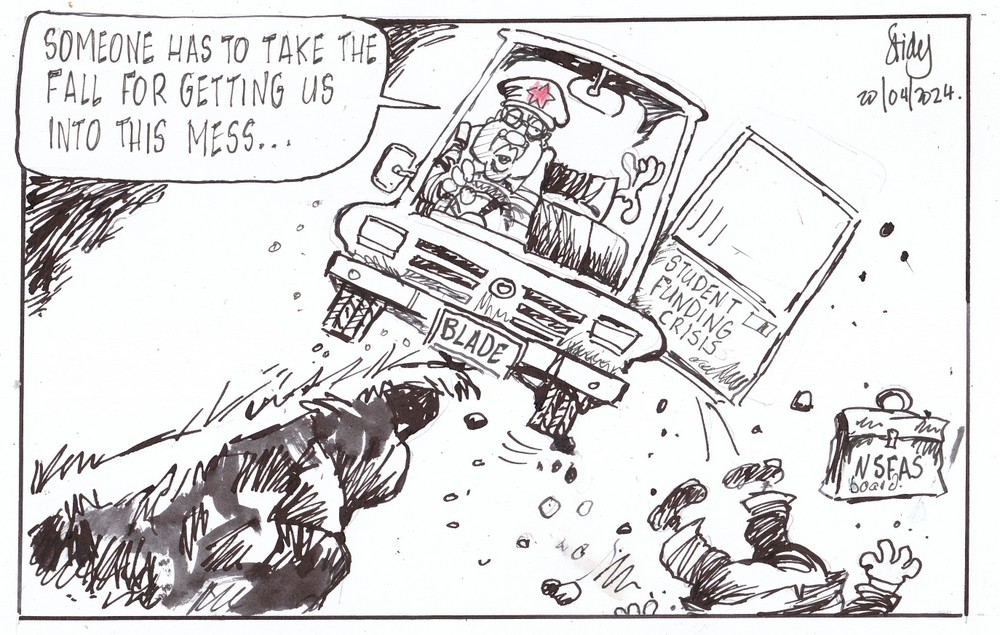

In these turbulent times, where salesmen-cum-saviours of the Donald Trump sort have taken to positioning themselves as champions of the “real people” (even though their rich-man lifestyles suggest otherwise) while attempting to impose their own versions of reality on us, the need to find a way to counter the torrent of misinformation spewed out regularly from both politicians and countless other, often conspiracy-based, outlets has never been more urgent. The question, of course, is how do we do this? In this fascinating book, Peter Pomerantsev, an expert on contemporary propaganda, gives materials to help answer this.

He starts by travelling back in history where he finds a fascinating example of how one man, now almost forgotten, set about undermining the Nazis during World War Two..

The son of an Australian academic, Sefton Delmer was born in Berlin and grew up speaking fluent German, although the fact that he was always perceived as a foreigner prevented him from ever becoming completely accepted. As the correspondent for the Daily Express, before the war broke out, he won the trust of the Nazi hierarchy, who, at that stage, were still eager to curry favour with and impress the British. He was invited to attend their militaristic mass rallies; he also got to meet the Fuhrer, Adolph Hitler.

With his wide experience as a journalist and his understanding of Gernam – and in particular Nazi – culture, Delmer was, in many ways, the ideal man to take on the Nazi propaganda machine and in so doing help undermine the German war effort. Operating with his team from Aspley Guise, a village near London, Delmer chose to do this by attempting to outplay Joseph Goebbels, the German Minister of Propaganda, at his own game.

Just as modern-day populists and tyrants have happily jumped onto the social media bandwagon, Goebbels quickly realised how powerful a medium of communication radio was and how it could be harnessed to serve the Nazi cause. In this battle for people’s minds – as Delmer came to realise – hard facts, reasoned arguments and evidence play only a secondary role. The emphasis is on making people feel they are special, that they are a part of a common destiny. In other words, propaganda works not because it convinces or even confuses; it works because it creates a sense of belonging. There is no effective way to counter it which does not take into account the need to belong that propaganda satisfies.

Delmer also realised there was little point in trying to make his broadcasts appeal to the “Good German” because that would be a case of preaching to the already converted. His aim was to win over the ordinary citizens, those who considered it their duty to do what their government demanded even if they did not fully understand the implications. He did this by tapping into their lack of idealism, rather than any high-minded ideals they might possess.

Deliberately employing the course, salty language of the streets – and going out of his way not to appear in anyway pro-British – Delmer, used his broadcasts, to discredit the German leadership in the eyes of ordinary Germans by portraying them as well-fed parasites leading lives of amoral excess while they suffered. Later he would subtly adjust his approach to meet the evolving needs of the situation.

While it is still a matter of debate among historians as to just what extent this anti-propaganda helped turn the tide of the war against Hitler, Delmer’s broadcasts do appear to have been listened to by a remarkably wide audience inside Germany. In unpacking his life story, Pomerantsev also shows that there is still much we can learn from his insights and observations in the fight against authoritarian propaganda.

Indeed, one of the strengths of his quietly inspiring book is that it hums with contemporary relevance. In our polarised world of “us and them”, Donald Trump’s self-pitying speeches contain obvious echoes of Hitler’s in their emphasis on victimhood – America is exploited by immigrants and bled dry by foreign countries. He will change that if elected – make America great again.

A Ukrainian by birth, Pomrrantsev has also witnessed, first-hand, how Vladimir Putin – another self-serving character with grandiose dreams of recasting world affairs – employs similar tricks to manipulate the media and keep the Russian people in thrall of him. Following Putin’s brazen invasion of Ukraine, the author returned home to find a country, once more, under siege, where the barriers between the past and present had dissolved. Not only was Ukraine under military attack but the same patterns of propaganda, justifying the invasion, were being used – only this time Putin’s troops are insisting they have come to free their fellow Russian speakers from annihilation by the Nazis in Kviv…

What this all clearly demonstrated to him was that the need to find ways of offsetting these new versions of old propaganda put out by bullies and dictators while nudging people towards the truth remains as important now as it did back in Delmer’s time

published by Profile Books

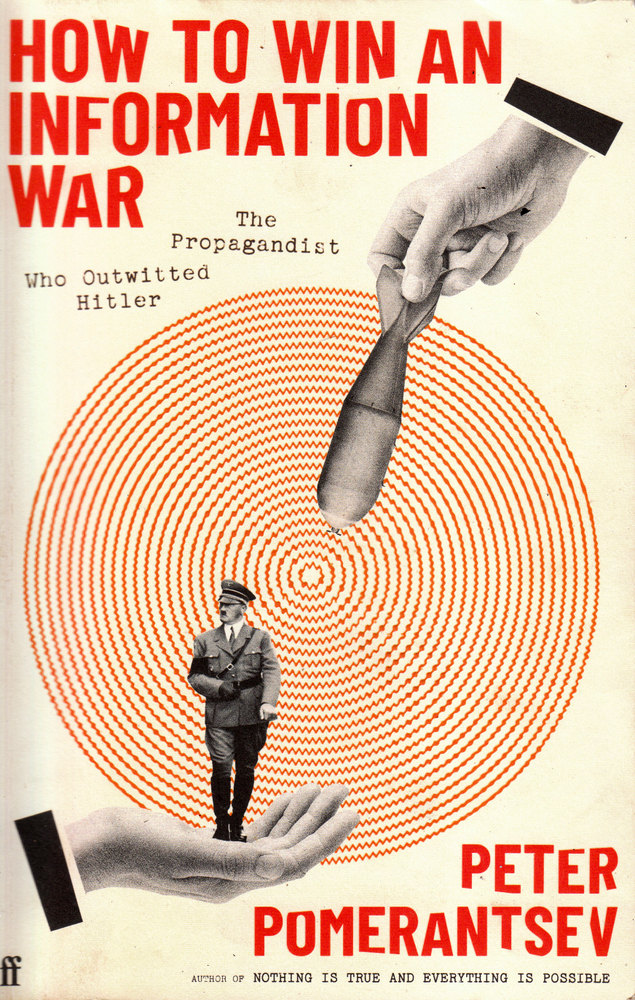

At its height, the Roman Empire – which replaced the old Roman Republic in 27BCE when Julius Caesar’s adopted son, Augustus, set himself up as the sole ruler of Rome – was the most extensive political and social structure in Western civilisation. It left an enduring mark on the history and culture of the West; its legacy lives on with us today in areas such as government, law, architecture, engineering and religion while the antics, intrigues and supposedly bizarre behaviour of the various emperors (Nero, Caligula, Elegabalus and Commodus being the more infamous examples) continue to provide an inexhaustible source of material for writers (and film-makers).

In this highly entertaining read, Mary Beard, the Professor Emeritus of Classics at Cambridge University, re-enters this familiar territory but comes at it from a slightly different angle.

While careful not to fall into the revisionist trap of completely rewriting history, she warns that many of the stories that have been passed down to us from the days of the Roman Empire should be taken with a pinch of salt because they often emanated from hostile historians who wanted to curry favour with the deposed emperor’s successors. As such, they can amount to little more than gossip, slander, hearsay and urban myth, sometimes written long after the events described.

Rather than concentrate on his individual foibles and failings, Beard is more interested in building up a picture of what the emperor actually did, the challenges he faced managing a vast empire and how he addressed imperial problems. In so doing she creates a colourful and impressionistic panorama of the ancient Roman world, with thematic chapters on how one-man rule worked, where the emperors lived, what his job entailed, what they did abroad, the role of women etc

Beard does not entirely ignore the juicy stuff or leave out the more scandalous bits that most ordinary readers might find interesting. She is interested in how many of the stories about the emperors arose as it is unlikely the empire would have been as mighty as it was and survived as long as it did if it was ruled by a series of deranged despots. Included in her text are many familiar tales of anxious rulers, artful poisoners, assassins, ambitious heirs, scheming mothers and wives, as well as loyal and disloyal servants.

While cautioning that we shouldn’t necessarily judge the Roman emperors’ behaviour by today’s standards, Beard also shows how they still provide us with important lessons on how to rule and a warning on how not to.

With the rise of autocrats in our age and with an emperor in the making – in the form of one Donald Trump – threatening to turn America into a dictatorship, the parallels between then and now become strikingly obvious…