Published by William Collins

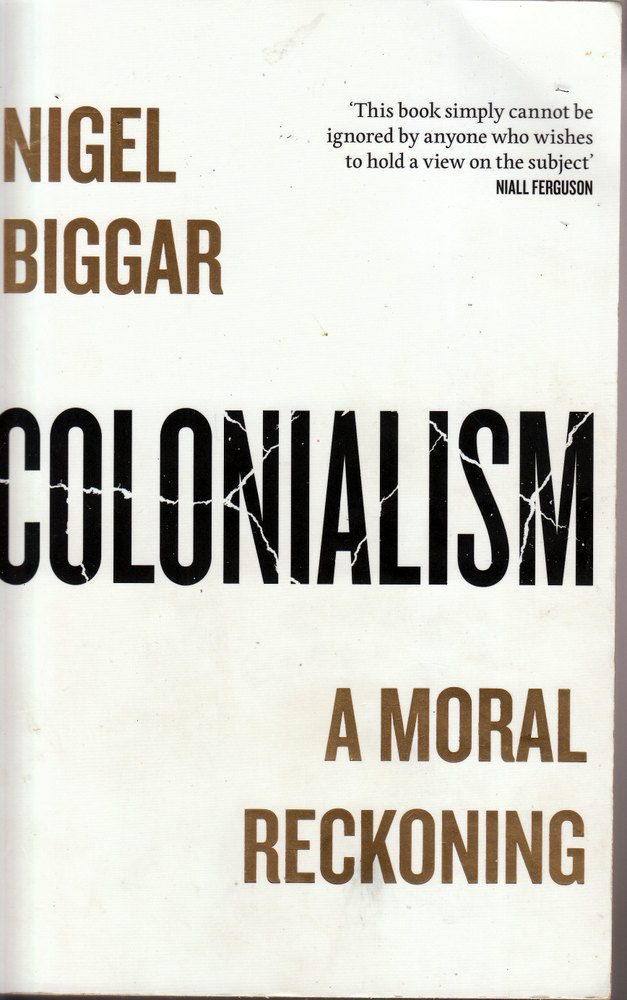

In this era of post-colonial guilt it has become commonplace in the West – and elsewhere – to see the legacy of the British Empire in essentially negative terms and to, likewise, dismiss those who took part in it as mostly brutes and racists intent on economic plunder and exploitation, with little regard for the welfare of the local inhabitants. While this view may satisfy certain ideological prejudices, the truth, author Nigel Biggar argues in this wide-ranging study of the subject, is more complicated and somewhat more forgiving.

As Regis Professor Emeritus of Moral and Pastoral Theology at the University of Oxford. Biggar is only too aware of the hazards of tackling such a fraught subject but thankfully he is not the sort of writer to be easily knocked off course. While his book does not spare us Empire’s failings, he is quick to correct a lot of the more erroneous, simplistic and dogmatic assumptions that have been made about it, as well as give praise where he feels it is due. Combining micro-details with a macro sweep, his scholarly, well-paced and critical overview contributes brilliantly to a reasoned reassessment of the subject.

What were the motives behind Empire? Was there a connection between colonialism and slavery? Are the claims of genocide justified? Did the colonial government fail to prevent settler abuse? Was excessive force used in quelling rebellions? These are just some of the questions he poses and then proceeds to examine in careful detail. In so doing, he attempts to redress what he perceives to be the biased and one-sided views of the more virulent “anti-colonialists” and alternative historians who he accuses of “allowing their condemnation to run out ahead of the data”.

Biggar appears vastly well-informed on the subject and his reading has been prolific. Behind the narrative lies a muscular, analytic mind that is not afraid to confront uncomfortable truths.

Some of the issues raised in this book will most likely prove contentious. Readers, however, do not necessarily need to accept all the author’s conclusions to enjoy his erudition, insights and the thoroughness with which he presents his case. Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning indeed serves as a corrective to the shallowness and superficiality that dogs so much supposedly “progressive” thinking these days.

published by Hodder & Stoughton

It is no secret that democracies around the world are in deep crisis with public trust and belief in elected officials at an all-time low. There are good reasons for this. In its ideal form, democracy is a system of government that exists not to protect privileges but to advance the equal rights and freedoms of the people. Increasingly, this no longer seems to be the case.

As most South Africans know only too well, service delivery has all but ground to a halt, our infrastructure is falling apart, corruption and incompetence seem to go unpunished and there is little accountability. As a result, many ordinary voters feel betrayed and excluded from the process.

This diminishing lack of confidence in the values on which Western society is supposedly based has, unfortunately, seen a lot of voters turning to authoritarian strongmen in the hope that they can fix it – think Donald Trump and his promise to “drain the swamp” (as his chaotic time in office only too clearly showed, he couldn’t. Indeed, he made it worse.).

In addition to this disturbing trend, democracy faces another existential threat from the growing number of autocracies around the world and, in particular, from China’s push for global supremacy. These countries seek to refashion the existing international order in their image and are intent on destroying everything democracy stands for. Elsewhere, leaders like Hungary’s Victor Orban are trying to undermine democracy from within.

For all its current failings, Dunst still believes that democracy offers the best form of government, not only because of the emphasis it places on the rights of the individual but because creativity and innovation have traditionally flourished in relatively open societies (as he points out, of the world’s twenty-five richest countries all but seven are democracies). What is required is for us to get our house in order.

Humming with contemporary relevance, Defeating the Dictators is his road map to how we can do this. Ironically, Dunst begins his journey by looking at the one autocracy that really does seem to work – Singapore. Unlike most autocratic states (and indeed many democracies), its system of government system is based on meritocracy – the notion that people should advance on their ability rather than because of political affiliations, personal connections or loyalty to the party in power. It is also relatively corruption-free, thanks to the strict enforcement of the laws, no matter how powerful you are or where you stand in the pecking order.

Elsewhere, Dunst proposes a variety of practical solutions to the problems confronting democracy. He stresses the importance of spending on infrastructure (especially digital infrastructure) as a way of improving the growth and functionality of the economy. He also believes in the importance of boosting our human capital capabilities by investing more in education.

A fundamental flaw he identifies in modern democracy is that too many politicians tend to put short-term politics before long-term strategic planning. In other words, too many leaders make decisions not on practical merits, but with the next election in mind. Some of his suggestions run counter to more conservative thinking. He believes, for example, that defeating autocracy hinges, in no small part, on welcoming immigrants because of their innovative spirit and willingness to work.

Dunst concludes his book with an extended warning against the way in which our hard-won liberties are being steadily eroded. It is something we need to act against if we want to stop the worldwide slide into dictatorship.