Once upon a time long ago, I found myself a very reluctant conscript in the Rhodesian Army. After I had completed my basic training in Bulawayo I was despatched to what the military hierarchy liked to call The Sharp End where I ended up patrolling with a curious mix of half-trained soldier-civilians in the hot, tsetse fly-infested, Zambezi Valley.

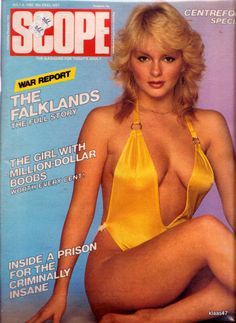

In my platoon was a stocky, jovial, young, former rugby-player who carried in his back-pack a centrefold he had torn out of SCOPE magazine. For him it was a ritual. Every night he would unfold the picture and pin it to the nearest tree; every morning he would take it down again, refold it and return in to his back-pack.

By the end of our tour poor Marilyn Cole – for that was the model’s name – had become so stained and crumpled and yellowed by the rain and the sun and the wind you could barely make out her shapely figure any more. It didn’t really matter. For us her ongoing presence was about more than mere sexual titillation. She had become a symbol of defiance, a link to the world we had left behind..

That was one thing the army did to you – it helped concentrate your desire for something you once took for granted into a craving that narrowed your focus intensely. Deprived of so much, the army taught me to take nothing for granted: a bottle of good wine, a meal in a restaurant, a hot shower, clean clothes, a comfortable bed.

Time passed. The war ended. I found myself at a crossroads, uncertain which way to turn. Worn out by seven-years of war, I decided, in the end, that I wanted another life, somewhere else. Scraping together what little money I had, I piled my few belongings in to my old Datsun 1200 and headed to South Africa.

The truth is that I didn’t have much idea what I wanted to do. I had studied English literature at university and held a BA degree so I had some notion of finding something where I could finally put that to use.

My sister, Sally, who had recently moved from Zimbabwe to Durban herself, kindly set up several interviews for me. The first of these was with Republican Press, at that stage, the biggest magazine publishers in South Africa. One of their publications was the self-same SCOPE Magazine.

I was not confident. As a virtual unknown, with no previous experience in journalism, I thought it would be virtually impossible for me to break in to this highly competitive field. In the interview I probably did everything the career advisers would caution you against – I arrived ill-prepared, I stammered, I was apologetic, I could barely string a coherent sentence together.

Oddly enough, this seemed to endear me to the company’s then MD, Leon Bennett. He told me I made a refreshing change from the usual spoilt, rich, presumptuous, white kids he had to interview.

As amateurish as they then were, he also saw potential in my cartoons.

I got the job. And so, by a strange twist of fate, I found myself working for the same magazine whose centrefold had helped buoy up my mood throughout my otherwise dispiriting National Service year.

These days some people, younger ones, don’t know about SCOPE but back then it had attained an iconic status in South Africa with it raunchy, irreverent, anti-establishment style of journalism, so at odds with the repressive morality of the times.

Describing itself, somewhat euphemistically as a “Men’s Lifestyle Magazine”, it had been launched in 1966 by Winston Charles Hyman with Jack Shepherd-Smith as its first editor. At the time, most of the magazines in South Africa were typically staid in tone, conservative it outlook, and anything but bold in design. SCOPE changed all that by pushing its maverick status and going where none had gone before.

Starting off as a newsy pictorial magazine it steadily ramped up its sexual content, then very much a taboo subject in the country. It began to publish lots of pictures of bikini clad girls. Later, it became famous for its nudes with strategically placed nipple stars.

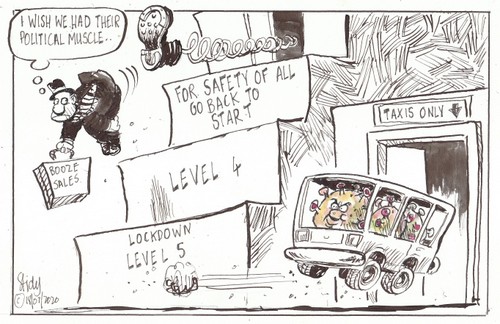

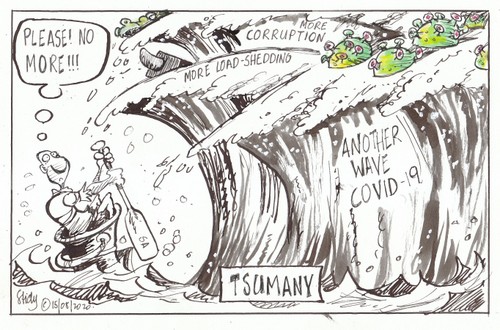

Typical SCOPE covers…

In the first flush of its glory days, the magazine sailed pretty close to the wind, constantly challenging the country’s strict censorship laws to see what it could get away with. It was routinely banned which only added to its allure and popularity.

Its circulation soared, advertising revenue increased. At its peak SCOPE was the largest selling magazine in the country reaching a staggering peak of 250 000 copies sold a week.

Shepherd Smith was succeeded as editor by a former Rhodesian, Dave Mullany. A tough, uncompromising figure not disposed to blind obeisance or toeing the line, he pushed the boundaries still further increasing the pin-up content and encouraging an even wider-ranging, freer style of reporting.

With his zippy and acerbic retorts, he turned the Letters Page in to one of the most popular and well-read sections of the magazine. Similarly reflective of his rebellious outlook was the space he devoted to rock music reviews.

In Richard Haslop – a lawyer by profession but as equally at home writing about music as playing it – he obtained the services of probably the most talented and knowledgeable rock scribe of his generation. Having grown up in an era of some of the giants of the music industry, what made Haslop’s reviews so appealing was his verve, insight and his eagerness to get you to listen to records as attentively as he did.

It wasn’t all just sex, big boobs, nipple stars and rock ‘n roll however. SCOPE treated serious matters seriously and produced a lot of good quality journalism.

One of the biggest scoops we got, while I was there, was an exclusive interview with wanted bank robber, Allan Heyl, a member of the notorious Stander Gang who had captured the popular imagination and achieved an almost folk hero status in South Africa. At the time Heyl, the only surviving member of the gang, was holed up in London (Stander himself had been shot dead by police in Fort Lauderdale, Florida).

More serious themes…

Another notable story which caused a huge furore, during my time, involved the pioneering heart surgeon, Chris Barnard, who had just returned from a big hunting safari in Botswana. One of the video operators, who had accompanied the group, had been so appalled by the cruelty she had witnessed on this hunt she leaked the story to SCOPE. We immediately published it. Very protective of his high public profile, an angry Barnard threatened to sue but the editor stood firm and he eventually backed away.

SCOPE’s vigour, humour, occasional vulgarity, big headlines and pin-ups gave it immense appeal with the young and, just as it had with my generation, it became a staple for South African ‘troopies’ serving on the border.

Ownership of the magazine changed hands when it was bought out by the Afrikaner-owned Republican Press. Because of their close connections with the government, its new corporate owners were never comfortable with the magazine’s perceived permissiveness but because of its big profit margins they were restrained from interfering too much. They did, however, fire Mullany when he chanced his arm, once too often.

With his departure something fundamental changed in the magazine. Deprived of its distinctive, self confident editorial identity it drifted, by default, in to the hands of lesser editors. It lost some of its sparkle and wit. Attempts were made to turn it in to an upmarket magazine for males but its old image had become too entrenched in the public’s mind for that to ever work.

As its circulation began to drop, management were eventually forced to eat humble pie and recall Mullany.

My four-year sojourn at the magazine fell in between his firing and rehiring.

As one would expect, the staff, when I arrived, were made up of a suitably ragtag group of disparate individuals. It was the heyday of “Gonzo” journalism and many journalists, inspired by the likes of Hunter S. Thompson, wore their outsider status as a badge of honour, galloping away from the sort of respectability and convention that was the hallmark of life in South Africa under the National Party (although this didn’t stop the government from implementing some pretty inhumane policies).

Tall, laid-back and laconic, Quentin – “Kanga” – Roux, the deputy-editor, moonlighted as a beach-bum, surfer and lifeguard at Winklespruit on the South Coast. He eventually married a beautiful young lady selected by SCOPE to sail around Mauritius as part of a tourist promotion and went to live on an island off Florida.

Chris Marais, our Jo’burg editor, played in a rock band before deciding that a small town in the dry Karoo was where he wanted to be (he now writes for South African Country Life). Bad boy Franci Henny, a feature editor, lived a borderline life of dissolution while nurturing an ambition to write the Great South African Novel.

Irony was the stock-in-trade of in-house humourist, Robin Hood, both in his writing and conversation. An ex-BSAP policeman with a wonderfully dry world view his weekly summary of the “Dallas” TV show plot line and acting was, for me anyway, far more entertaining than the show itself (which had a huge South African following).

My time at SCOPE also coincided briefly with that of Frank Bate, another brilliant and funny writer, whose booze and drug-fuelled escapades made him something of a SCOPE legend. He died at the relatively young age of fifty but managed to pack two lifetimes worth of living in to those years.

I also struck up an immediate and long-lasting friendship with Karen MacGregor, the first woman reporter to be employed full-time by the magazine. A highly-respected, award-winning, journalist, Karen would go on to work for the Times Higher Education Supplement in London, write for Newsweek and London newspapers such as The Independent and The Sunday Times, and later become the founding editor of the on-line publication, University World News.

Where she led, others followed: Esther Waugh, Ann Jones and – another good friend – Mandy Thompson (now resident in Majorca) all worked at the magazine while I was there.

As a misfit-of-sorts myself I enjoyed the living-on-the-edge work ethic and environment and felt quite at home with SCOPE’s slightly disreputable image.

I was given my own column, PERISCOPE, a mix of quirks and oddities gleaned from around the world which I illustrated as well. I also worked as a re-write man taking stories we had got from elsewhere and converting them in to a more racy “SCOPE style”.

In 1988, I allowed myself to be lured away when I got offered a job on the Jo-burg-based Laughing Stock, a sort of local version of Britain’s Private Eye. Although it employed some highly gifted humourists (among them Gus Silber, Jeff Zerbst, Harry Dugmore, Arthur Goldstuck and the creators of South Africa’s most successful ever comic strip, Madam & Eve, Stephen Francis and Rico), the market wasn’t ready for us and the magazine folded after a year.

Back in Mobeni, Durban, SCOPE had also been having a hard time of it.

In a way it was responsible for its own plight. For years it had campaigned against the country’s censorship laws but when, after independence, these were relaxed it found it could not compete with the more heavyweight overseas girlie magazines such as Playboy and Penthouse which had been allowed to enter the South African market.

The magazine continued to be published but it had gone in to terminal decline. In an effort to boost sales they messed around with the formula, it went through several incarnations but none of them worked because, in a sense, it couldn’t make up its mind whether it was one thing or the other – an unpardonable sin in the industry. Time had also dulled its edge, values had changed, society moved on.

It continued to slide inexorably, a hollow shadow of its former rumbustious, controversial, self.

The plug was finally pulled in 1996 by which time I had long since moved away and was happily ensconced as the first-ever, full-time political cartoonist for the Witness newspaper in Pietermaritzburg.

But that is a story for another day….