There is no risk of overstating it: 2020 was a horrible year. With levels of worry, anxiety and depression reaching a new high level mark, I finally realised emergency solutions were called for. After puzzling it over, I decided the best thing to do would be to try and end the year on a high note by escaping – if only briefly – from all the mania and talk surrounding Covid-19.

And so we took to the hills, heading up into one of the more remote and isolated areas of the country – the Great Karoo, which forms part of South Africa’s vast, high-lyng central plateau. Here, I hoped, I would be able to rid my mind of the ever-looming spectre of the pandemic and reboot my soul.

Officially, there were three of us on the expedition – myself, my artist sister, Sally Scott, and Professor Goonie Marsh, the former-head of the Department of Geology Department at Rhodes University and a very useful man to have around because of his extensive knowledge of all things Karoo. Also, he is very good company.

The route Goonie had plotted for us, took us through the tiny hamlet of Riebeek East where the famous Voortrekker leader Piet Retief once owned the farm, Mooimeisefontein. Retief would later go on to negotiate land deals for his people in what is now my home turf, KwaZulu Natal, before his unexpected assassination at the hands of King Dingaan of the Zulu.

The road out of Riebeek East.

Riebeek East Church.

There was another reason I wanted to check out Riebeek-East. An ancestor of mine, on my father’s mother’s side, Lt Colonel Richard Athol Nesbitt, had served here as a sub-inspector with the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police (FAMP) back in 1866. Besides a few drowsing cows lying on the side of the road, there was not much sign of life. Cruising down the town’s empty streets, I tried to visualise what it must have been like when the sub-inspector came riding into town, correct and erect in his policeman uniform, on top of his handsome horse. It must, I concluded, have felt like some sort of banishment because, even today, Riebeek-East feels cut off from the outside world.

This point notwithstanding, I found I was developing a bit of a kinship with Richard Athol. It was almost like he was along with us for the ride. On my way down to Grahamstown, where Sally lives, I had stopped for a breather at Fort Brown, on the Great Fish River, another nondescript outpost of Empire where he had served. This was not the only place where we were to dog each others shadows. In 1872 Nesbitt was promoted to Acting Inspector and despatched to the next town on our journey, the more substantial Somerset East, nestling under the massive bulwark of the Bosberg.

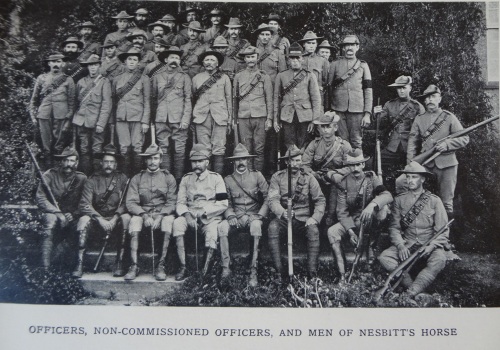

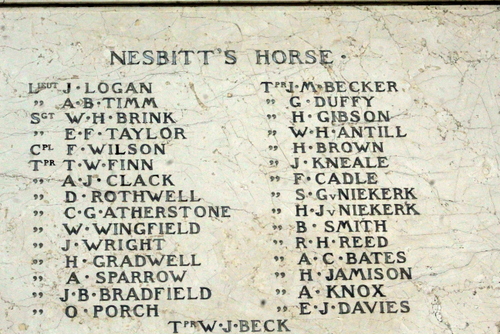

In 1878 the FAMP were militarised, as a unit of the Colonial Forces, and renamed Cape Mounted Riflemen (CMR). The unit would go on to play a prominent role in the numerous conflicts that broke out within the Cape Colony and around its borders, as a result of the Cape government’s expansionist policies. Later, Richard Athol would come out of retirement and – at the request of the Colonial Government – raise and command Nesbitt’s Horse which, in his own clipped words, “served in most of the principal events of the [Anglo-Boer) war, with Lord Robert’s march – Paardeburg, capture of Bloemfontein, Johannesburg, Pretoria and in clearing the colony of rebels.”

The Lt Col was obviously not one for uneccessary sentiment or wasting words…

1902 found him resident in Grahamstown. His military exploits are commemorated in the impressive monument which stands in front of the town’s old Methodist Church. An entire side-panel is devoted to those members of his unit who lost their lives in this bitter conflict.

We finally parted company with our ghost passenger somewhere up on the Bruintjeshooghte, just south of Somerset East. We were now travelling in less familiar territory. Ahead lay the vast Plains of Cambdeboo, immortalised by the author Eve Palmer in her classic book of the same name. You actually pass by the farm – Cranemere – where she grew up and lived and you can still see the same dam that provided them with their lifeblood – water.

The Plains of Cambdeboo from Bruinteshoogte, looking towards Graaff Reinet.

The Plains of Cambdeboo looking back towards Somerset East.

The small town of Pearston, where the great palaeontologist Dr Robert Broom once lived, is also on the road although, like many of these Karoo dorps, it now looks a little fly blown and past its best. Of Broom himself, more later.

Pearston street scenes.

Pearston.

Beyond that the world lay wide and empty around us until we finally got to Graaff Reinet – or the “gem of the Karoo” as it is sometimes called because of its neat, shaded streets and beautiful period houses – set in a mass of wild-looking hills with the Valley of Desolation to the west and, overlooking the town, the prominent landmark of Spandau Kop. Established in 1786, it is South Africa’s fourth oldest town and has its origins as a far flung frontier settlement on the very edges of the old Cape Colony.

Just outside of town, on the road to Murraysburg, there is a stark, simple monument to Gideon Scheepers, the Boer military leader who was court-martial-led and shot here on the 18th June 1902, by the British authorities. It was – according to Goonie (who also has a solid grasp of the region’s history) – a severe punishment which turned him into an instant martyr for the Afrikaner cause. As opponents in the Anglo-Boer War, I wondered if Gideon and Richard Athol had ever crossed paths?

Beyond that, the road climbed steeply up the Oudeberg Pass. Before I knew it the Plains of Camdeboo were below us, then out of sight. At the turn-off, to Nieu-Bethesda we stopped for lunch on the side of the road, under one of those abrupt, flat-topped, mountains that rise out of the plains, like talismanic guardians, throughout the Karoo…

The Karoo is a land of sun, heat, and stillness although, as if to defy my expectations, a light drizzle began to fall as we unpacked our picnic basket on the tail-gate of the bakkie. The summers can be scorchingly hot, in winter the night temperatures regularly drop well below freezing point. Rainfall is erratic, drought common.

It was not always so. There was a time when ceaseless rains poured down upon this ancient land, leaving it covered with inland seas, lakes, and swamps. Millions of strange-looking reptiles and amphibians roamed around and then died here; in our era, their fossilised remains have made the Karoo world-famous for palaeontologists. This brings us back to that pioneer of the profession, Dr Robert Broom, who did so much to uncover their secrets.

As we drove deeper into the interior the hills became barer, even more silent. There was little sign of habitation although, every now and again there was the occasional windmill or wind pomp just to remind you that people lived here. The road wound on and on, empty and devoid of traffic, so much so that driving along it eventually became like a form of meditation.

Originally this vast area was occupied by the San, aboriginal hunters, small in size and few in number, who drifted with the seasons and the herds of game. Of these animals the springbok is, undoubtedly, the most emblematic of the Karoo, their bodies evolving, over time, to deal with the hardships of life in this arid country. Despite the devastation wreaked by the early white hunters, which saw this beautiful animal being exterminated over much of its range, the springbok population has begun to rise again, now that their commercial value has become appreciated.

Later, the San themselves were hunted down or driven into the swamps and deserts. In their place came trekkers, traders, missionaries, and explorers, who braved the fierce heat, moving with their wagons and animals into the harsh dry interior. With them, they bought their religion. Nearby Murraysburg, named to honour the Reverend Andrew Murray, was originally a church town resorting under the full control of the Dutch Reformed Church up until June 1949 when it was placed under the control of the local municipality.

Just beyond the spot where a large sign announced that we were leaving the East and entering the West Cape, we came to an imposing white-pillared gate with a sign “Oudeland” next to it. Here we swung right, driving down a dirt road dotted with caramel-brown rain puddles. In every distance, the plain was sparse and bare although we did pass the crumbling ruins of an old barn and kraal with the inevitable wind pomp standing like a sentinel behind it. Moving fast, the clouds cast a storm light across the buildings. I wanted to look for the species of lark that had these scrub-strewn grasslands all to themselves but with more rain threatening now wasn’t the time for it so we plugged on.

Cresting a rise, the farmhouse and outbuildings came in to view in a valley below where – Goonie explained – a sill of hard, erosion-resistant, dolerite had cut through the softer sedimentary rocks. A small, seasonal, stream ran through the middle of it. The main farm complex was situated on the one side amongst a mass of poplar, gum, and willow trees and fields of grazing merino sheep; the lush green colour of the lucerne pastures, in which they were feeding, contrasting sharply with the stark, elemental beauty of the semi-desert that surrounded them.

Our house lay on the opposite bank, just above a belt of prickly pears. As we drove into the fenced yard we were greeted by a brown horse and a small herd of multi-coloured springbok. Such colour morphs are extremely rare in the wild (in fact, they are so unusual they were venerated by the San) but these white, or leucistic, forms are mostly the result of selective breeding to meet the needs of hunters seeking exotic trophies. It is a practice that has caused some controversy because the genes which cause these colour variants are actually recessive and so could weaken the species.

I am not a hunter and I get no joy in taking life, so I was delighted to share the animals’ company just for its own sake, especially when – every now and again and for seemingly no particular reason – its various members started leaping in stiff-legged bounces known as “pronking”, in which all four hooves hit the ground at the same time. The small herd was, the owner’s wife explained, all orphans who had been hand-reared and loved to the point where they had become family pets. Each one had its own name. I was especially taken with the one very friendly individual who had one blue eye and one green.

The house itself was built in the usual airy Karoo style with white-washed walls and a wide verandah on which you could sit and gaze out over the distant lonely blue mountains. Inside the appliances were all modern although the stuffed head of a large buffalo bull, as well as that of a puzzled-looking Zebra, added a slightly incongruous touch.

I was up at daybreak. We were lucky that morning. Overnight, the rain clouds had all blown away. The sky above us was a strange intense blue, wind-cleaned, limitless, and crisscrossed with lazy scrawls of thin cloud. There was a lovely lyrical quality to the landscape, to my eyes, it all seemed intoxicatingly clean and remote. Although I am not from these parts, I felt totally at home in this indivisible, self-contained world.

Not much shelter…

In this sort of country, there is almost no shade or protection from the elements although our morning walk did take us up to a stony ridge in which there was an overhang with bushes growing at its mouth. On its walls, we were excited to discover several faded examples of San rock art. I had no way of knowing how old they were – possibly thousands of years?

From the cave entrance we looked down over a large dam which reflected the changing weather in the sky above. Water lines of geese and duck and dabchick cracked its surface. Such open stretches of water always come as a surprise in this thirst-land. For the birds it must indeed seem like manna from heaven..

Back on the path, Goonie came to an abrupt stop, pointed his walking stick in the direction of an exposed sheet of unsuspecting, layered, grey rock and declared: “That looks like just the spot for a fossil!”. Sure enough, when we went down to investigate, we found several tiny fragments of fractured fossilised bone. With my untrained eye I would never have suspected they were there and would have passed the site by without a sideways glance.

Just the spot for a fossil. Prof Goonie Marsh.

The fossil embedded in the rock. Pic courtesy of Sally Scott.

Leaving them undisturbed we continued down to the dam wall. From its top we stood, awed by the view, as the escarpment retreated away; each ridge exposing new gullies and rough broken ground and more valleys until finally reaching the horizon, where the pale ramparts of the distant range of mountains raised themselves. Then we walked on, feeling buoyant and light and energised. Sally, with her artists eye (as opposed to Goonie’s more scientific one) was struck by all the strange patterns and details in the landscape and regularly stopped to record them.

Later, when it got too hot for walking, Goonie and I climbed in to the circular reservoir around the back of the house and had a swim. It felt good, splashing around like I was a young boy again…

That evening we sat with our drinks out on the verandah. The earth was still in twilight shadow. In the distance massed, bulging, cumulonimbus clouds gathered above the mountain tops. As the sun sank so they changed shape, form and colour.

All felt well with the world. Far from the madding crowds, I finally began to get some sort of harmony between body and mind. Looking back over the journey, I also felt I had established another link with my past, learnt a little bit more about how I got to be who and where I am…

My sense of contentment did not last. Back in Grahamstown all the talk still centred on the pandemic and the overcrowded hospitals and the beach and liquor ban. I couldn’t help but feel a little deflated. The happy little bubble I had created for myself in the wilds of the Karoo suddenly seemed far away. That is the problem with fantasies – sooner or later they get punctured and you are back with harsh reality.

GALLERY:

.

A fabulous account of our journey back to sanity. Thank you for recording it, Ant. I will be revisiting this post whenever the dark forces of the world overwhelm me.

LikeLike

My pleasure – and a big thank you for suggesting and organising it. I look forward to many more forays into our past, as well as this beautiful country!

LikeLike

Loved it – and the beard by the way!

LikeLike

So good to hear, Sue. I am afraid my beard is not quite as rampant and luxurious as the Professor’s one is! Like me, he is a bit of an old hippy…

LikeLike

Great, vicariously pleasurable, read. It conjures up another time as well as place that is a welcome escape from one in thirty in this city having the disease . Stay safe !

LikeLike

Thanks, Julian. It was just the tonic (if temporary) I needed. The figures here make pretty grim reading too, especially now we have the new SA Variant to contend with as well. I am just glad I can hide away from it all up here on the farm. Take care of yourself!

LikeLike

Good to take a break from the madness Ant! Very evocative and enjoyable read

LikeLike

Thanks, Penny. Glad you were able to escape to your High Country as well!

LikeLike

Wow that a wonderful journey you all went on and so beautifully captured in your writing. Thank you for sharing it. Beautiful images too

LikeLike

Thanks, Mary-Ann. It was just what the doctor ordered! Hope you managed to find time to chill out as well?

LikeLike

Wow Stidy, what a wonderful end to my birthday to read this superb masterpiece of writing, with The Boss – Bruce Springsteen – providing the soundtrack in the background. I’m sure you’ll agree he and the E Street Band are the perfect companion for such road trips and for reading about them afterwards. Lovely photographs too!

LikeLike

Thanks, Ken. I am honoured that you found time to read my musings on your birthday! Good choice of music too. I really must do something about my car CD player so I can listen to the Boss when I travel. Or maybe I just need to update my music system – and probably my car as well!

LikeLike