published by 4th Estate

The 1994 Rwanda genocide, conducted mainly against the Tutsi minority ethnic group, was one of the great traumas of the twentieth century. During roughly 100 days between 500 000 to 662 000 people were killed. The scale and brutality of the genocide sent shock waves around the world although no country intervened in the slaughter.

The immediate trigger for the massacre was the downing of the jet carrying not only the Rwandan President Habyarimana but also his Burundian counterpart, Cyprian Ntarymira. Determined to avenge the slaying of their president, thousands of youth militia went on the rampage, bent on exterminating not only Tutsis but any Hutu deemed as being hostile to the regime. The long-standing tension and resentment between the two cultures provided the combustible fuel that sparked a raging riot.

In the aftermath of the genocide the rebel Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), who swept through the country and restored some degree of order, was originally seen as the good guys – or at least the more virtuous of the various warring factions. It is a reputation which does not always stand up to scrutiny as author Michela Wrong shows in her often chilling but always compelling account of what transpired.

Wrong, who won deserved plaudits for her book about the rise and fall of Mobutu Sese Seko, In the Footsteps of My Kurtz, and who, as a reporter, witnessed many of the massacres that took place in Rwanda, is perfectly placed to write about the genocide.

In her introduction, she admits, however, the difficulties she had obtaining accurate and reliable information in a society where duplicity and lying are seen as a political virtue but her book nevertheless contains much intriguing anecdotage from many of the principal characters involved. It also has the ring of authenticity.

Opening her account with the assassination in South Africa, of the popular but now exiled Patrick Karegeya, the former Rwandan chief of Intelligence and one-time close friend of President Kagame (the book’s title comes from the sign the assassins left hanging on the door of his hotel room while they went about their grisly business), she then moves back in time, tracing the trajectory of the RPF from its origins in the Ugandan conflict of the 1980s to its present-day position as the ruling party in Rwanda. In the process, she strips away the carefully constructed façade and shows how a rebel movement that once inspired awe and respect and pitched itself as the party of ethnic reconciliation, has become, in true Orwellian tradition, as corrupt, autocratic, vindictive, ruthless and power-hungry as the regime it overthrew – and equally guilty of its own atrocities.

One of the many questions that springs to mind on reading the book is how ordinary people, people such as you and me, were able to act with such barbarity? In part, this can be explained by the country’s toxic history which allowed one side to dehumanise the other and consider them less than human. As Wrong observes “brutality is contagious” and the whole Great Lakes area has a long history of violence. Another interesting question that emerges from the book is just who shot down the jet carrying the two heads of state? Although the truth has never been completely established, much of the evidence points in one direction

Blended with vivid descriptions of place and character, Wrong manages to weld together all the myriad strands of this difficult and shocking period of recent African history in a language that is simultaneously poetic and down-to-earth. The result of much painstaking research, Do Not Disturb demonstrates with terrible clarity the ultimate potential consequences of racism, militarism and authoritarianism.

published by Melinda Ferguson Books

South African journalist, academic and former anti-apartheid activist, Malcolm Ray has set himself an epic challenge with this book – to attempt to explain how the social and economic turmoil that has engulfed so many post-colonial African states came about. This was always going to be a tough task but it is one he tackles with determination and enthusiasm and backs up with a great deal of hard research and careful analysis.

Fundamental to his argument is the whole concept of Growth Domestic Product (GDP) which has become the core creed of most countries’ financial planning. Ray devotes much of the earlier part of the book to explaining how it evolved and how an obsession with it has come to dominate economic thinking.

As originally conceived, the drive to identify and prioritise GDP had its merits. At the end of the Second World War, for example, the United States, as the world’s leading economic power, launched what became known as the Marshal Plan whose purpose was the revival of the world economy after the devastation caused by the conflict. As US Secretary of State George C Marshall, after whom the plan was named, made plain when discussing it, the doctrine was not directed against any country but against “hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos”. Noble in intention the plan initially worked well enough although by the 1970s (and thereafter) those innocent days were long gone. Since then, a growth-at-any-cost-doctrine and unchecked free-market economics have resulted in what Ray calls bandit capitalism which, in turn, has often gone hand in hand with bolstering up repressive regimes – like Zaire’s kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko. Poor countries have found themselves coming increasingly under the control of mostly American multinationals.

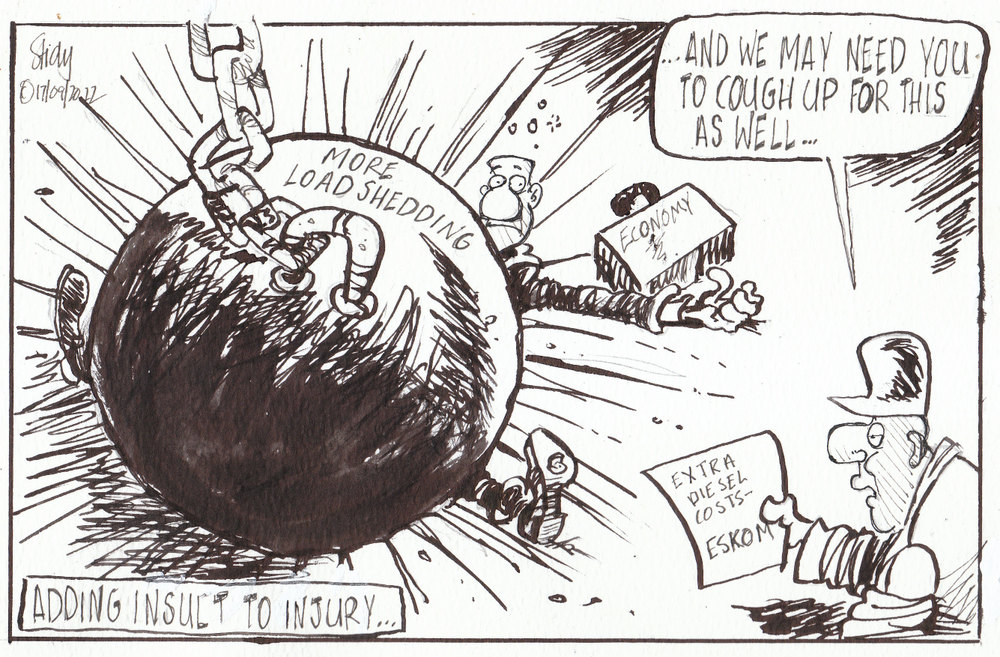

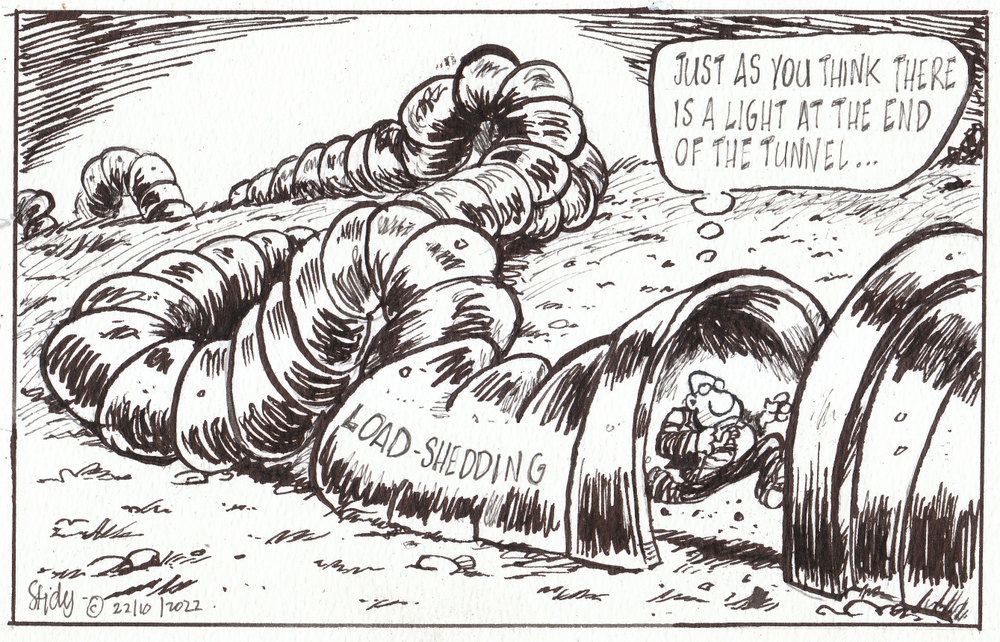

Perhaps hardly surprisingly, Ray examines the role played in all of this by organisations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, who were tasked with monitoring developing countries’ finances and whose extremely unpopular austerity measures had plunged many countries into seemingly intractable debt traps. He also shows how the whole aid for trade doctrine pushed by the US and its subsidiaries has in many cases been a tragic, epic failure.

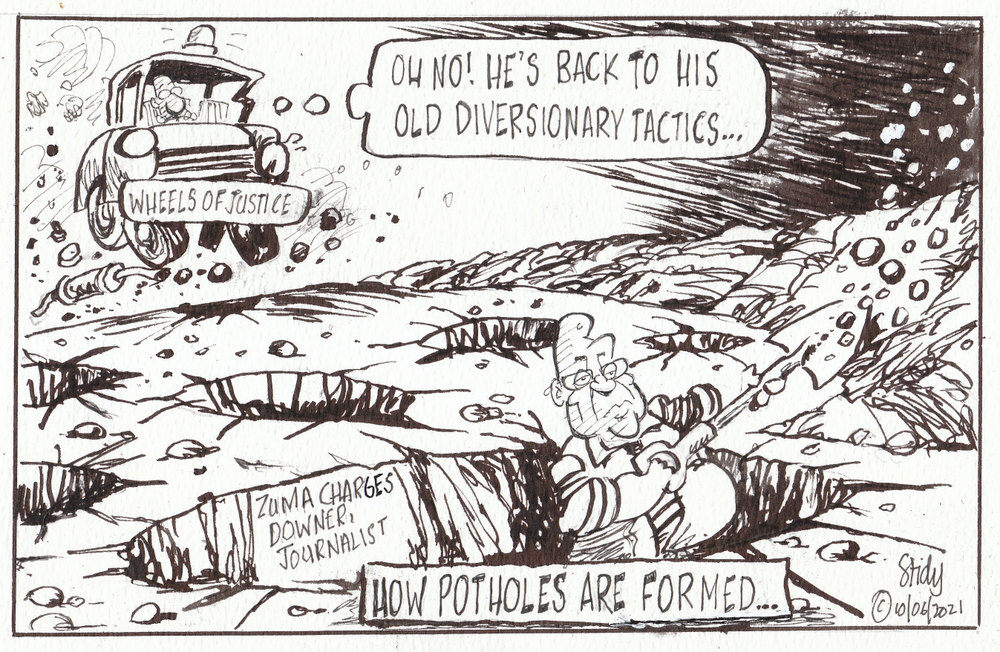

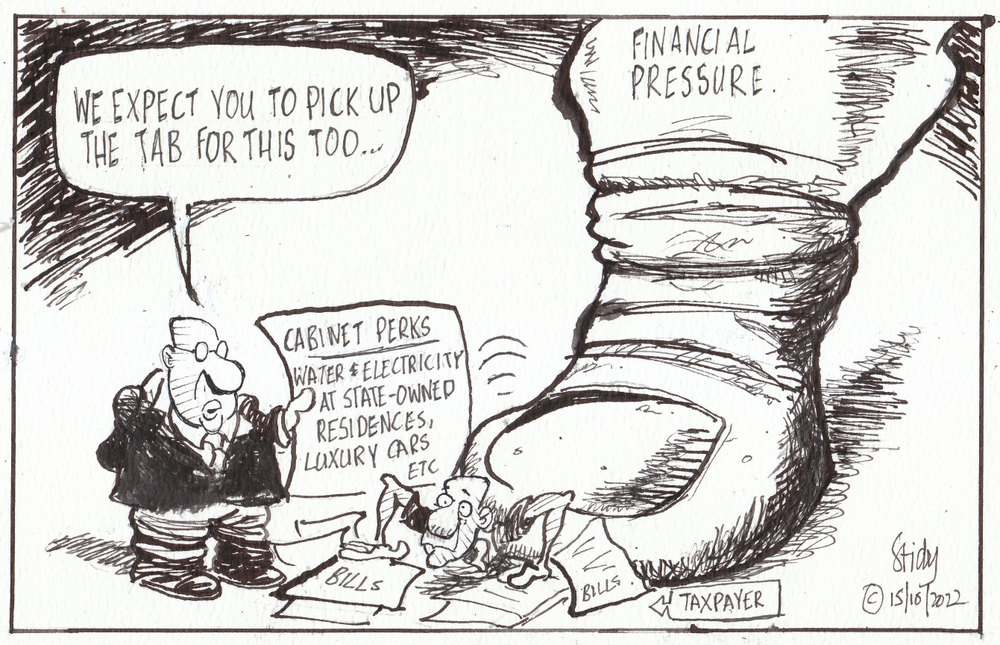

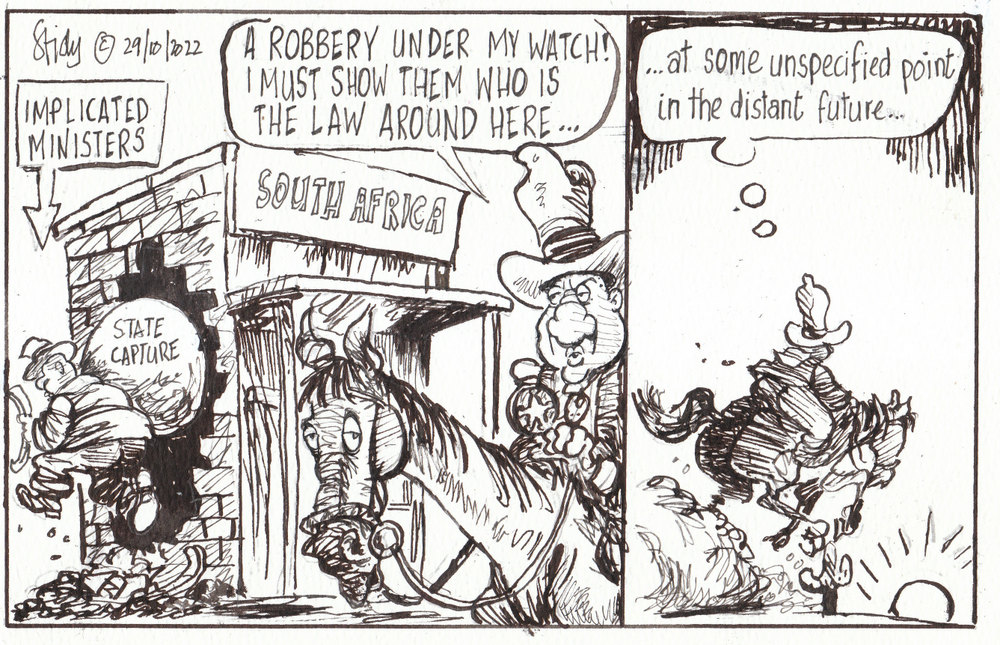

South African readers will find the chapters devoted to this country especially interesting. Ray provides a compelling and convincing narrative to explain how President Thabo Mbeki’s ambitious economic reform programme came undone, paving the way for the rise of the opportunistic, predatory, Jacob Zuma whose “oligarchy was a populist manoeuvre to seize the ill-gotten gains of an old oligarchy, not for the benefit of the people who made it, but for himself.”

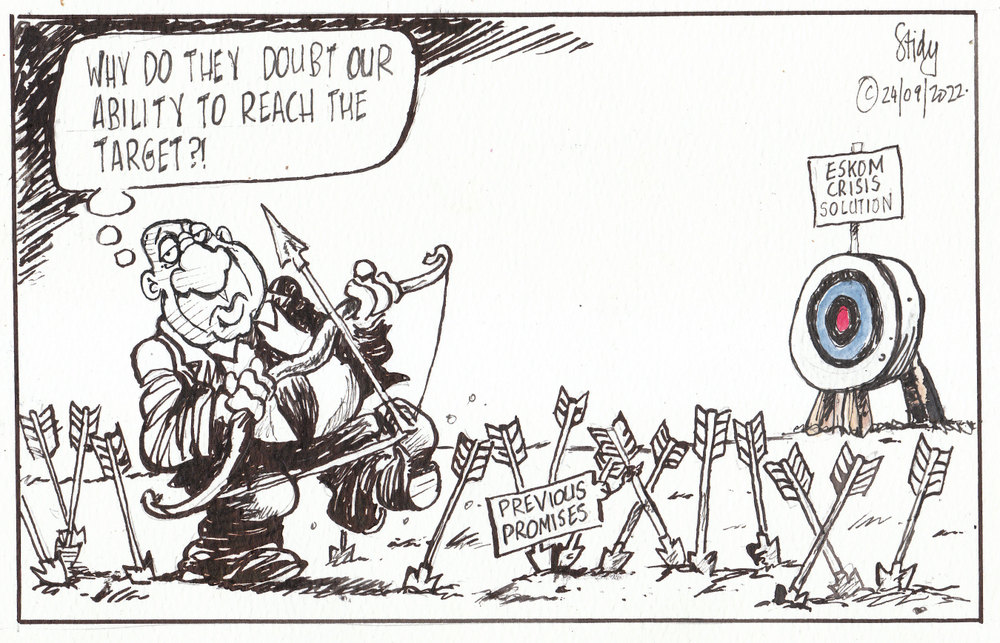

Well-informed, broadly convincing and certainly alarming, Tyranny of Growth is a timely and important book. The strength of Ray’s argument lies in his humanising Africa’s descent into economic chaos and also his posing of the all-important question – who exactly does the growth at all costs doctrine benefit when it has led to the marginalization of the continent and produced not only growing joblessness but an almost obscene inequality in the distribution of wealth?

The answer, he suggests, lies in the flawed economic model we are using…