This is the story of a little duck – although I would caution you against calling him that to his face. It would most likely deeply offend him. For as far as this particular waterfowl is concerned he is not a duck, he is a CHICKEN! The fact that he is relatively small, short-necked, large-billed, web-footed and has a distinctive waddling gait is of no account to him. So what if his ancestors branched off on their own separate evolutionary tree way back in the mists of time? Likewise, why should he be bothered by all that Linnaeus terminology about classes, family, genera and species?

For this little duck, it all boils down to a question of “belonging” and he knows precisely where his true home is. In the chicken run, surrounded by all his chicken friends.

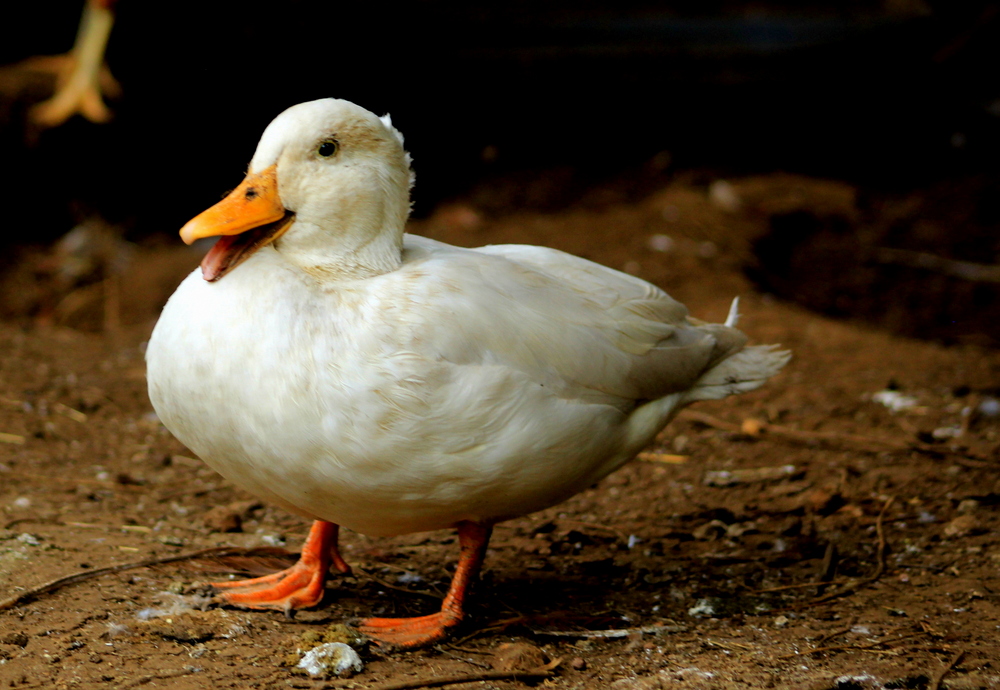

To understand how Plucky-the-Duck-Who-Thinks-He-Is-A-Chicken (which is his full name but from here on, I will simply refer to him as Plucky) came to identify so strongly with a type of bird whose size, form, shape, patterning, colour and habits of behaviour do not quite match his own it is necessary to go back to the curious circumstances surrounding his birth.

Plucky’s parents were two normal Dutch Quacker Ducks and like many happy couples, they decided to raise a family. Eggs were laid. The mother dutifully sat on them. After the requisite period of incubation, the eggs hatched – all except one which the mother then abandoned, presumably believing it to be infertile. Or maybe after twenty-eight days, she just got bored of sitting. I am sure I would have done the same if placed in a similar predicament.

On the odd chance that she might have quit her parenting duties a little too soon, we decided to place the one remaining Dutch Quacker egg in an incubator full of chicken eggs. Amazingly, there was, indeed, a life form in it who then proceeded to bludgeon his way through the shell. This happened at more or less the same time as all the chicken eggs commenced hatching.

The act of identification seems fundamental in such situations and since the first thing Plucky saw, when he emerged into the light was a whole batch of hatching chickens it is perhaps hardly surprising that is what he decided he must be.

Despite their evident differences, it would probably have been better for all if we had let the whole matter rest there. Instead, once he got a little older, we decided to be hard-nosed about it. A little human intervention was called for. Because of Plucky’s obvious confusion over who and what and why he is, it seemed to us some psychological counselling was in order. A little friendly guidance, a nudge in the right avian direction. A course in Duck Deep Therapy.

It so happened that our neighbour had a pair of Quacker Ducks and three ducklings, the latter more or less Plucký’s age. When he offered them to us, knowing we had a big pond on which they could cavort and play and do other duck things whereas he did not, we saw this as a perfect opportunity to integrate Plucky with his own kind.

We would put him in the pond with them.

Two boxes were duly placed on the water’s edge, the one containing the family of ducks, the other, a bewildered Plucky. We released him first. Some deep-rooted instinct obviously did kick in for he took to his new environment like a…well… proverbial duck to water. Once he seemed comfortably established in his new liquid home, we released the inmates of the other box.

It was at this point that our plan to re-integrate Plucky with his kind began to unravel…

On being released from their box, the two parent ducks panicked and charged off into the surrounding shrubbery, leaving their confused offspring behind. The abandoned ducklings, in turn, saw Plucky floating on the other side of the pond, and, recognising him as one of their own kind, went paddling in his direction. Clearly appalled by the sight of this small flotilla advancing, full steam towards him, Plucky went into escape mode With a violent clattering of wings, he launched himself over the sheep enclosure fence, gained altitude, hovered briefly and then tumbled, out of sight, down into the valley below.

Where he landed I had no idea. With a dull foreboding, I set off with Michael Ndlovu, our farm manager, to scour the countryside, kicking through leaves, looking under bushes, clambering over rocks and staring until my neck ached. To no avail. The little duck had simply vanished into the ether. Feeling both a little teary and angry with myself for being so presumptuous as to assume I understood Plucky’s needs better than he did, I trudged back home.

The next morning, I was woken in the early hours by a huge commotion in the hen house. When I stumbled out in the freezing cold with my torch to investigate, I discovered one of the hens had accidentally laid an egg in her sleep and then worked herself up into a state about it. Miracle of miracles, I also found a very cold and forlorn Plucky huddled up against the outside gate to the enclosure. As I approached he looked up at me beseechingly and uttered a few feeble ‘quacks’. He had somehow found his way home in the dark. It seemed pretty clear we had not taken into account Plucky’s resolve or his loyalty to the only real family he had ever known.

Again, this is where we should have left it but in the same perverse fashion, we made the snobbishly human mistake of thinking we knew best. If we tried one more time maybe it just might do the trick.

It didn’t.

They say birds of a feather flock together but that was definitely not the case here. Clearly traumatised by the thought of sharing the pond with these feathered imposters, Plucky took to the air again, disappearing into the same valley. A fruitless search followed. Twenty-four hours later I found him curled up outside the hen house door.

That settled it. Plucky could stay with the hens.

Although it didn’t enter our reckoning at the time there is another reason Plucky’s decision to remain in the hen house proved a wise one. Within six months of his return, all the other ducks had disappeared, either killed off by local predators or migrating to new pastures. Not so Plucky. He has continued to prosper and flourish. He has now outlived three successive Rhode Island Red roosters (Rowdy, Randy and Rufous) and I suspect he may outlast the fourth (Randolph).

Happily ensconced in his home, he continues to charm us in many ways: the earnest bumbling walk, the body shape, the head scrunched down, the gentle eyes so full of understanding, the endless preening, the look of sleepy disgruntlement when I shine my torch into the hen house late at night to make sure they are all okay, his dogged insistence on flying from the top perch when I open the same house each morning and crash-landing, in a maelstrom of dust, into the ground below.

To bring some variation into their existence, I used to open the hen house gate every afternoon and allow the motley band to free range through the garden. Plucky came to love these big adventures. Jaunty but resolute, he would stride off, along with the rest of the gang, like he was David Livingstone searching for the source of the Nile. Sadly, the resident predators soon got wind of this daily routine and when one of our prize Bosvelder roosters got snatched, in mid-cock-a-doodle-do, by a lurking Caracal I was forced to put an end to their little outings into nature.

Of the three it was our original rooster, the larger-than-life and boisterous Rowdy who Plucky developed the closest bond. They became inseparable friends. He has kept a much lower profile with his two successors, Randy and Rufus, and initially treated Randolph with a deep suspicion bordering on active dislike.

Maybe it was a male domination/territorial thing. A need to assert himself. Show who is the head honcho in this yard. For a while, it even appeared that Plucky held the upper hand. Each morning, just after sunrise, I would open the henhouse door. Out would shoot the burly Big Red Rooster, with the determined little Dutch Quacker Duck in hot pursuit. Around and around the run they would go until, tiring from the effort, Plucky would suddenly stop and go for a drink of water and then perform his ablutions with a self-satisfied air.

I think a peace conference – presided over by a panel of senior hens – must have been called because suddenly a truce was declared. All hostilities ceased. Individual egos were set aside in the interests of the flock. While they haven’t become exactly close friends, Plucky and Randolph now treat each other with wary respect.

Plucky also went through a brief but rather trying period when his sexual urges got the better of him. He began to emanate a discernible lustiness and became obsessed with the idea of finding a mate. In this case: a chicken mate.

He is at a serious disadvantage in this respect because he is much smaller than the hens. Undeterred, he waited until one hen was happily flapping around in a dust bath and then leapt on her and had his wicked way. Later, Plucky developed a hopeless fixation on another Rhode Island Red hen, trailing around after her with a moonstruck look on his face. He even insisted on sharing the nesting box with her whenever she wanted to lay an egg, getting very excited when it appeared.

I think he secretly hoped there might be the embryo of another little Plucky inside…

Alas, his attempt at courtship was a dismal failure. The hen obviously considered him an unsuitable paramour and grew increasingly agitated with his unwanted advances. In the end Plucky began to make such a nuisance of himself I was forced to put him in his own separate run for a few days to allow his passion to cool. Luckily, it did…

As he has matured and grown older, Plucky has adopted a more fatherly, protective, proprietorial attitude towards the hens. As a long-serving member of the Parliament of Fowls, I think he now sees his role as that of a senior statesman whose job is to lend a guiding hand. He takes his duties very seriously. As the sun is abdicating each day, he stands at the hen-house door and waits until he has been able to mark off every hen as present and accounted for, before entering the chamber himself. Usually, with much pleased-as-punch quacking and a wagging of his curly tail…

Despite the fact he is not a chicken (I must insist – do not tell him that!), the rest of the flock have accepted Plucky’s presence with equanimity and good grace. For his part, Plucky is quite happy to go on living in his totally deluded state. I envy him for that ability. Every night when I go to lock them up I see him huddled up happily amongst all his chicken pals…

There is obviously some sort of moral fable in all of this. Taken together, the inmates of the hen house provide a shining lesson in tolerance towards foreigners and acceptance of social diversity. I am only too happy to admit to a degree of anthropomorphism – an impulse to identify with him – in my attitude towards Plucky.

He reminds me of the humans I love best – the ones who don’t quite fit in but find their own quiet space in society nevertheless…

GALLERY:

A young Plucky…

Fully grown, Plucky starts to explore his known universe…

Plucky is very conscious of his appearance and spends an inordinate amount of time preening himself…

…but he still often ends up a muddy mess…

As a Dutch Quacker Duck, Plucky has opinions about a lot of things and is not afraid to express them…

“Alright!” quacks Plucky the Duck, “That’s enough about me for now…”

THE END