: If you are in a bad mood go for a walk, if you are still in a bad mood, go for another walk.”-Hippocrates

I can feel the sun on my back, already warm as toast, as I set out through the farm gate following the road that leads down to the protea field and then past the tall pines where a clamorous row of black crows are having a huge argument over which direction to fly. I know in a general way where I am headed and what I will most likely encounter along the way although each day always brings its subtle differences. I don’t, normally, wonder too deeply about my motivations for doing what I am doing. Going for a walk is just something I do and enjoy. I find it healing. Outdoor therapy. It helps me to think. It is my form of meditation. If I am feeling down in the dumps it gets me – mostly – back on the right track.

There are no limits to where I walk. I am quite happy to keep exploring the same patch of ground because over time you develop a sense of intimacy with it that comes from an accumulation of particular observations. Likewise, there is a special fascination in testing one’s expectations in less familiar backgrounds. The important point, I think, is to be able to relish both the ordinary and the extraordinary.

The habit of walking manifested itself at a very early age. When I was about three years old my father, an airline pilot with a yen for country life, decided to relocate us from our house in the then Salisbury (now Harare) to a smallholding in Umwindsidale, about thirty kilometres outside town. He chose to call our new home “Dovery” after the crooning Cape Turtle Doves that were such a feature of the place. For me, their call remains one of Africa’s most beautiful, evocative and comforting sounds.

My main memory of the property is the view which was spectacular. From our front verandah, we looked over an open stretch of land, extensively cultivated, along whose edges the Umwindsi (now Mvinzi) River flowed, its path marked by an outline of dark green. Beyond this fertile plain stretched a further succession of hills and valleys, blue and hazy, each one becoming successively paler, in turn, as they rose to meet the sky. From an early age, I liked to create worlds of my own, in which I could slip away unnoticed and undisturbed and the countryside that surrounded our home provided plenty of places where I could do just that.

The Umwindsi was a lovely little rivulet that tumbled and crawled and blundered its way through a network of rocks, roots and tall shady trees. For a young child, it was a magical place and I spent a lot of time adventuring up and down it, playing in the pools and exploring its secret places to see what lay hidden there.

It was also the ideal preparation ground for our next grand adventure – a move to a remote farm at the northern extreme of the Nyanga mountain range.

The farm occupied a broad stretch of land, mostly valley but bordered on two sides by mountains. Jutting out from the main range were several castellated buttresses which stood like imperious guardians, mute witnesses to the goings on below. Along the floor of the valley stretched miles of grassland with woody patches, winding rivers which fed into one another and soft hills inset with elephant-coloured boulders, many covered with old stone walls, left behind by some forgotten people. Over it hung the intense blue sky of Africa.

The land on our farm hadn’t been worked for many years and felt wild and untamed. At the night the wind would howl down from the mountains and the very air seemed to seethe with phantoms, both good and bad. They whispered to me as I lay in my bed with only a flickering candle, on the table next to me, to keep the shadows at bay. In the moonlight, the whole landscape beyond my window seemed to possess a strange alchemy all of its own, a spirit ancient and impassive permeating the land.

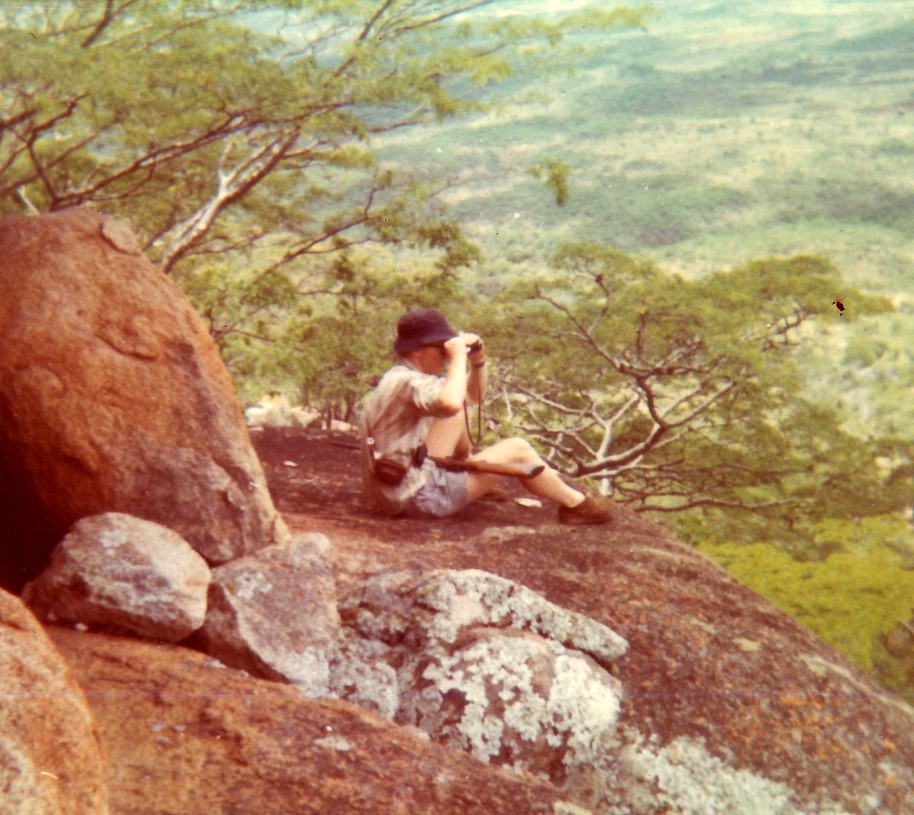

There was much to discover and endless opportunities for exploration. Most mornings when the sky was clean and ready for whatever lay ahead I would set out into the wilderness to see what I could find. I learnt to watch, wonder and recognise all the landmarks: the curves in the road, the shape of the hills, the twists and turns of the mountain streams, the outlines of the fields, the size and weird contortions of the baobab trees. No horizon seemed too far away. The more I saw, the more the place insinuated its way into my soul. It deepened my love for Africa. Sometimes I would go with my elder brother Pete – an avid birder even back then – mostly I would go on my own with just the farm dogs for company. My memory of these walks and the years on the farm have never left me.

It wasn’t just at home that I walked. Bastions of robust sportsmanship, all three of the boarding schools I attended -REPS in the Matopos, Plumtree on the Botswana border and UBHS in the Eastern Highlands – encouraged healthy outdoor activities, seeing it as an essential element in character-building. Most weekends would find me exploring the surrounding countryside.

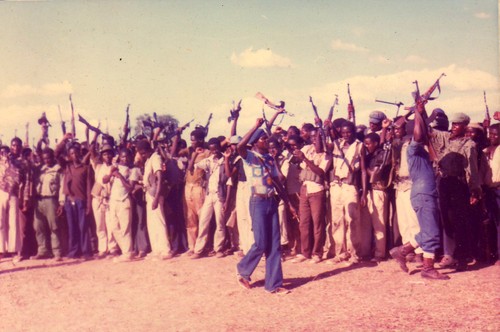

Eventually, the idyll came to an end. My life took a turn for the worse. Bad replaced good. War broke out. I got called up.

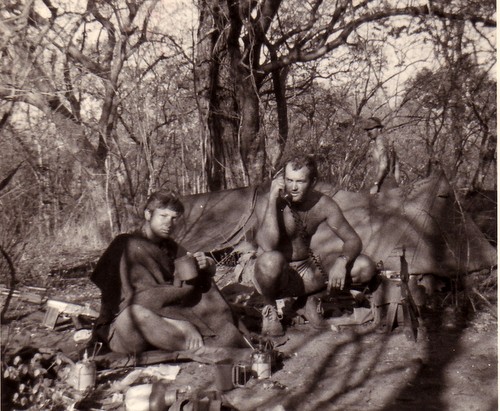

As an ordinary foot soldier in the army, I got to do a great deal of walking although most of it was not voluntary or even pleasant. Having bullets and mortar bombs whizz past me didn’t add to the enjoyment.

Getting shot at or mortared was not the only thing which occupied my mind patrolling in the stupefying heat of the Zambezi valley. On foot in Africa, one will sooner or later have a hair-raising experience with a wild animal. Of them all, I think it was the lone Black Rhino I was most scared of. To have one suddenly come crashing through the bushes is not an experience I want to repeat too often although I had my fair share of scrapes with this cantankerous character.

Still, the army toughened me up, got me superbly fit and introduced me to some wonderful new scenery so I mustn’t grumble.

The Rhodesian Bush War finally dragged on to its inevitable conclusion. I got discharged. Like all wars, the conflict marked our lives. It left a lasting legacy. In my case, I don’t think I emerged from it suffering from Post Combat Stress Syndrome or anything as dramatic or personality-changing as that. Still, it did leave me with a vague sense of melancholy, restlessness and an inability to settle down. Unsure what to do, the horizons seemed to close in around me. I felt trapped and constricted.

Bored stiff with my office job in the Mining Commissioner’s office in Gweru, I resigned and moved onto my parent’s new farm at Battlefields, near the Midlands town of Kadoma. Needing time to think, I walked and walked. By the end of it, there was hardly an inch of the farm I didn’t know. Walking had, once again, become my solace, my cure. It also made me realise it was time to move on. To go somewhere new. To start my life again in a place where I wasn’t surrounded by the constant reminders of the futility of what I had been through.

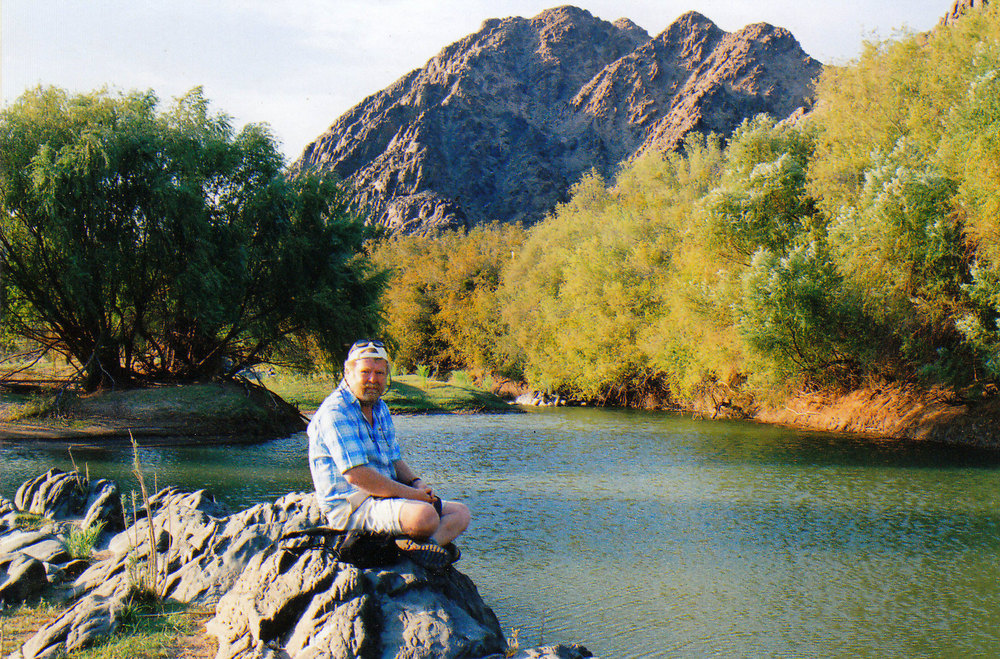

And so I packed my bags and moved to South Africa. With me went my nostalgia for landscape which I quickly transferred to my new surroundings. I set about exploring the country. I went on birding expeditions to Marakele, Mapungubwe, Kruger and the Richtersveld. I trundled through the Little Karoo and Baviaanskloof. I walked on the Wild Coast to the sound of crashing breakers. With my sister, the artist Sally Scott, and her family I made countless trips to the Drakensberg. We slept in caves, hiked along numerous mountain trails and plunged into icy rivers.

The Drakensberg had a different feel from the mountains I had grown up amongst in Nyanga. Higher, more precipitous, austere, jagged, cold and with fewer trees they were inhabited by a different set of gods and mountain deities. I loved it all the same. Climbing them, I always felt I had risen above the material plane and entered another, more enchanted, realm. The scenery and views left me breathless.

When I wasn’t out walking, I worked as a political cartoonist in Pietermaritzburg. As I got older, I grew increasingly disenchanted with city living. Some friends suggested I move up to their farm, high on a hill overlooking the Karkloof Valley. Viewed through the soft, filtered light of the swirling mist, there was something dream-like about its beauty; my heart was immediately smitten with delight. I accepted.

Moving into the country changed the shape of my life. It helped renew my sense of deep connection with the natural world. I spent many happy hours tramping over a familiar circuit of paths, seldom meeting a single person en route. Revelling in the sense of discovery and freedom that comes with this, I developed an increasingly close and intimate relationship with the local flora and fauna. However, nature still managed to spring surprises on me.

Lockdown came. I had always thought that the advances in modern medicine would provide a solution for everything but Covid, at least initially, proved me wrong. The virus transported us all back to the fear-ridden, helpless days of the Great Plague. It reminded us of just how vulnerable we still are and demonstrated that we are still at the mercy of the whims of nature.

Over the next two years my life – like many others – took on a slightly surreal aspect. As part of the locked-down community, I found the days blurring together. Whether it was Monday or Friday came to hold no interest for me. Alone in the house, isolated from the world, I lived in silence and solitude, with only the sound of birdsong, the whistle of a reedbuck, the howl of a jackal and the croaking frogs to sustain me. When I went to town, which was not often, I talked through a mask to other people wearing masks. It felt a little weird and dehumanising at first but I got used to it.

The national confinement stretched on through the months that followed with intermittent breaks. In the end, I learnt to get used to a world with little direct communication, so much so that I almost began to prefer it that way. Again, it was my walks which brought me the most relief, gave meaning to my life, helped me feel less trapped and provided me with a sense of quietude which conquered despair. I was lucky living in the country because the people living in town weren’t permitted to go beyond their front gates whereas I had our entire farm to roam over.

If you had to ask me then why I walk so much, I would have to concede that – apart from the obvious health benefits – it stems back to a longing to be the boy I once was, innocent again and seeing the world for the first time. My walks remind me of a more carefree period of my life. More than that, though, they have become part of a growing awareness of myself, an increasing reflectiveness and a developing sense of my place in the world and the environment. It nourishes my sense of self-sufficiency. It makes it easier to exist in these tumultuous times.

Time has, of course, dissipated some of my innate restlessness but while I still have the energy in my legs and air in my lungs I intend to keep walking…