Now that I look back on it, I see the one thing that has stopped me from sinking too deeply in to the Slough of Despond during the long, lonely, months of lockdown has been my chickens. At a time when the whole world seems to be going to hell in a hand-basket, they have continued to provide me with a sense of normality, comfort and reassurance. Quite indifferent to the great human drama being played out around them they have stuck to their daily routines – eating, drinking, sleeping, fornicating, scratching around in the straw, attending to their ablutions, egg-laying, crowing, clucking – with cheerful insouciance.

In fact, you can take it from me: kooky, sassy, loveable and sometimes just plain hilarious, chickens make wonderfully entertaining companions. Chickens are cool! Chickens rock (why else would one of my favourite old British Blues groups call themselves Chicken Shack?)!

One of my roosters…

…doing the rock ‘n roll.

Okay, so they may lack some of the attributes and superior skills possessed by other members of the bird world. They are not as big and strong as an Ostrich. They are not as stately and graceful or have the elaborate courtship rituals of the Grey-crowned Crane. They can’t sing like a White-browed Robin-Chat, nor do they possess the exquisite beauty of Narina Trogon. They can’t suck nectar out of flowers while hovering like sunbirds. They can’t fly or dive as fast as a Peregrine (in fact they are downright clumsy aviators who should be prohibited from taking off unless in an emergency) and – unlike the fierce, regal, Eagle – you probably won’t find them featured on any countries’ coat of arms. Nor can I imagine any Roman legion marching in to battle with their standard bearer carrying a stylised replica of a chicken mounted on a metal pole.

On the other hand, they do do make excellent weather forecasters which is why you often find them positioned on top of wind vanes. Chickens have other virtues and talents that might have escaped your notice – they are easy-going, respond to kindness, produce high-quality garden fertiliser and have an unmatched ability to lay prodigious quantities of healthy, wholesome eggs.

A lot of folk think chickens are stupid, with beady eyes and pea-sized brains. That is not my opinion at all. In their domestic arrangements and social gatherings they are actually remarkably organised. Like humans, there is a clear-cut, ladder-like, social hierarchy with the ones on top enjoying clear advantages and special privileges denied to the others – like prime position at the food trough and first choice of roosting spot.

Proof that chickens have aesthetic sensibilities…

Like me, this one is a great admirer of Shona sculpture.

The order of dominance is usually established by one hen giving another hen a quick peck. Hence the term “pecking order” coined, back in 1921, by the Norwegian ornithologist Thorlief Schjrelderup-Ebbe, a man who spent a lifetime immersing himself in barnyard politics.

When you introduce new members to an existing flock they usually spend couple of days sizing each other up. Once they have worked out who fits in where, they live in surprising harmony thereafter. President Donald Trump could learn a few lessons from a chickens ability to accept strangers and integrate with one other.

Chickens form alliances and cultivate social networks. They learn who to avoid and who to cosy up to. They pick special individuals to sit close to. My two beautiful Bosvelder hens, for example, always roost together in the same spot every night. They are clearly very fond of each other, affectionately huddling together and clucking contentedly before falling asleep.

It is very easy to slip in to the anthropomorphic trap of attributing birds with human emotions but I do think they are capable of friendship, empathy and grief. And who cares if the scientists don’t agree with you or look with scorn on such misdirected displays of sentimentality? I sometimes think the boffins would benefit from getting away from their test tubes and cold laboratories and getting a little more romantic in their theories…

Of course, I am talking exclusively about hens here. Roosters are another matter altogether.

I actually have two chickens runs. The first is the domain of The Red Brigade – the descendants of the Rhode Island Reds who formed the nucleus of my original flock. The second belongs to The Motley Crew – the non- Rhode Island Reds (although a few Reds have infiltrated their ranks).

The Red Brigade.

The Motley Crew.

Originally each run had it own rooster but in the end the combined racket became more than I – and our guests – could stand. Roosters can be incredibly competitive in their attempts to outshout each other. The principle function of this non-stop crowing is, of course, the proclamation and defence of territory, as well as impressing their multitude of wives. More than that, they seem to take an aesthetic pleasure in their own performances, always looking immeasurably pleased with themselves after another ear-shattering outburst.

Rowdy warms up…

Rowdy lets rip…

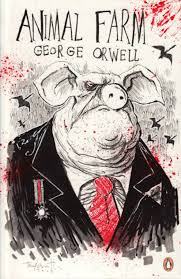

Vain, pompous and boastful – and definitely not as smart as their female counterparts – it is very easy to see why many authors have chosen to satirise human society by endowing roosters with human qualities. In Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Nun’s Priest Tale, for example, the fox plays on Chanticleer the Rooster’s inflated ego and overcomes his instinct to run by insisting he would love to hear him crow, just as his amazing father did, standing on tip-toe with neck outstretched and eyes closed. Although he succumbs to this flattery, Chanticleer finally manages to outwit the fox by playing his own trick back on him.

Alas, Motley-Fool Too, the son of the original Motley Crew Bosvelder rooster, Motley-Fool One, was not nearly as crafty or as lucky as Chanticleer.

Motley-Fool One

Motley-Fool Too

It happened like this. I had chosen to let the Motley Crew out to forage in the garden one glorious, sunny, afternoon. While all the hens were doing sensible hen-like things – hunting for seeds, chasing grasshoppers, pecking at invertebrates – Motley-Fool Too, as every bit as raucous as his late father, was staging his own concert under the Avocado Pear tree. Suddenly, there was an almighty commotion which cut him short right in the middle of what would turn out to be his Requiem to Himself…

By the time I got to where he had been standing, all that remained was a few fluttering feathers and a lingering cloud of dust demarcating the spot that Motley-Fool Too had just claimed as his own. After a search, Michael Ndlovu, our farm manager, found his lifeless body crumpled up in a nearby rock outcrop.

If I was a nature detective I would say the perpetrator of this violent crime was probably a Caracal as I have seen them around the chicken run before. Or maybe a Serval. We get them too. They like chickens in whatever shape or form they come.

Although he had plenty of good examples to learn from – including Maestro Rufus in the adjoining run and Nicholson’s noisy rooster, down the road, on the next door farm – Motley-Fool Too never quite mastered the signature Cock-a-Doodle-Do of his species. What we got instead was an abnormal, strangulated, high-pitched, almost unrecognisable version. Repeated again and again ad nauseum…

After Motley-Fool Too got himself snuffed out, in the very prime of his life, I often found myself wondering whether the culprit – whatever it was – found his hysterical banshee wailing as irritating as I did and decided to put a stop to them once and for all. Or maybe it just got sick and tired of Motley- Fool Too’s overweening vanity. Hubris and falls, and all that…

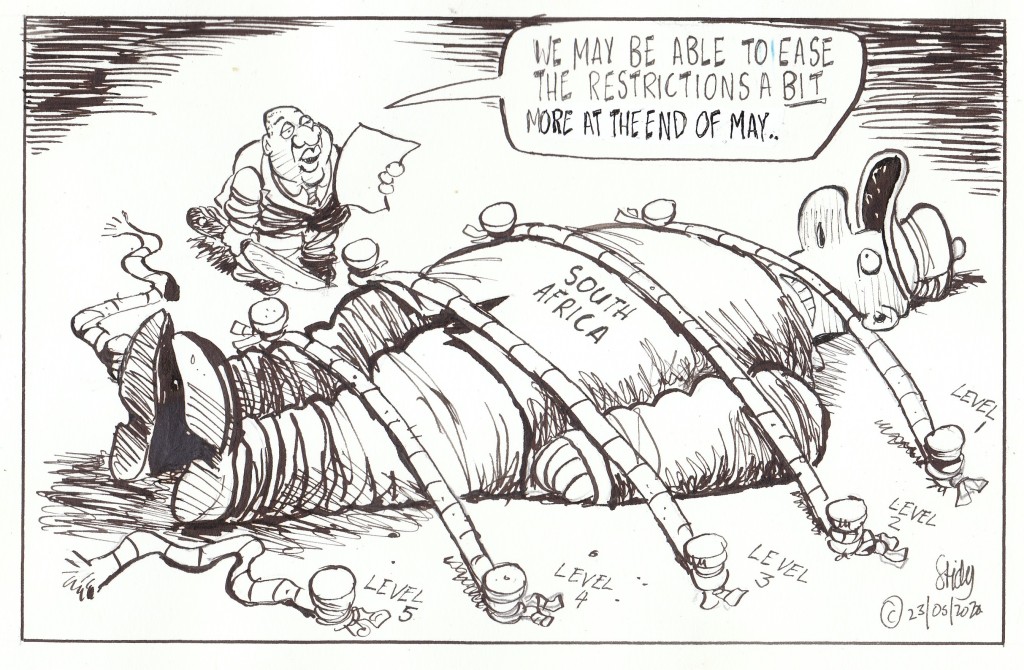

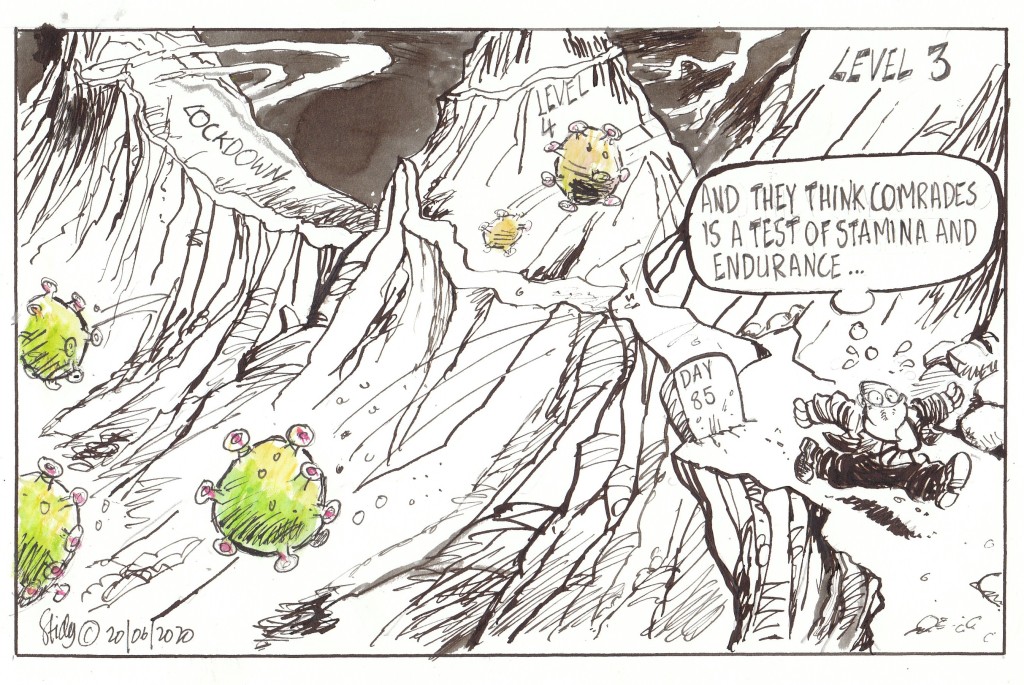

Having discovered a ready source of fast food, the predator kept returning to the scene of the crime putting my entire flock of some forty-odd hens and one remaining rooster in huge panic. This left me with no other choice but to place my chickens in Level Five lockdown, banning all movement outside their designated runs.

Unlike the late, unlamented, Motley-Fool Too, I must confess I have a real soft spot for Rufus the Rhode Island Red rooster, mostly because he is sufficiently comfortable in his own manhood not to feel the need to constantly assert himself (President Trump could learn from him too). Which means I get to sleep at night. He is also very protective of his harem. I approve of that too.

Holding up my end of the deal, I provide my little work-force of breakfast manufacturers with amusement as well as food. I relish my role as Chicken-Whisperer. It is very satisfying and helps keep me grounded, especially in the midst of the current anxiety. Way back in time – before the river of life started hitting all the jagged rocks and tree trunks and whirlpools and waterfalls – my parents handed me the responsibility of looking after their chickens. Thus there is a nice sense of continuity and coming home about what I am doing now. This is my heartland. I have returned to my farming roots.

Two of the hens in the Motley Crew run were acquired in rather unusual circumstances. My sister, a Social Anthropologist living in Mpumalanga, had been invited to attend a Xhosa ritual in Grahamstown. As part of her contribution to it, she purchased two bush hens from a seller on the side of the road, just outside Mbombela. While she was overnighting with me they laid two eggs. I decided to put them in the incubator. Abracadabra – 21days later out hatched two chicks who I promptly named Penny and Susan.

Like my sister, I can not help but think they were a gift from the ancestors (I am sure my parents had a hand in the selection). They both grew up to be exceptionally good mothers, forever going broody, so whenever I want to hatch a clutch of eggs, in the natural manner, I invariably use them.

Penny the bush hen.

Susan the bush hen. Both good mothers.

There is another oddity in my flock and that is Plucky-the-Duck-Who-Thinks-He- is-a-Chicken. How he came to be in my run is a story in itself – his was the only duck egg to hatch in an incubator full of hatching chicken eggs. Chicken is all Plucky has ever known and all he wants to be. A brief attempt to reunite him with his own kind ended in dismal failure (completely traumatised by the experience, he flew off and hid in the bush for 24-hours before making his way back to the chicken run. When we repeated the experiment, he did the same).

A very young Plucky at Nursery School…

Transferred to the Big Run, a young Plucky attends to his ablutions.

Plucky hero-worshipped our original rooster, the larger-than-life and boisterous Rowdy, and followed him around with all the devotion of a religious convert. He has kept a much lower profile, however, with his two successors, Randy and Rufus. I think he is a little wary of them or else he thinks they don’t have quite quite the same charisma.

Plucky and his idol, Rowdy the Rooster.

Rufus the Rooster and Plucky. Slightly more wary…

Plucky went through a brief but rather trying period when his hormones suddenly got the better of him. He became obsessed with the idea of finding a mate with whom he could mate. In his case: a chicken mate.

He is at a serious disadvantage in this respect because, being a Dutch Quacker, he is much smaller than the hens. Undeterred, he waited until one hen was flapping around in a dust-bath and then leapt on her and had his wicked way. He also developed a hopeless crush on another hen, trailing around after her with a moonstruck look on his face. He even insisted on sharing the nesting box with her whenever she wanted to lay an egg, getting very excited when she did so.

For her part the hen grew increasingly agitated with his unwanted affections. In the end Plucky began to make such a nuisance of himself I was forced put him in the other run to give his passion time to cool off. Luckily, it did…

As he has matured and grown older, Plucky has adapted a more fatherly, protective, proprietorial attitude towards the hens. As a long-serving member of the Parliament of Fowls, I think he now sees his role as that of an elderly senior statesman whose job is to lend a guiding hand. He takes his duties very seriously. As the sun is abdicating each day, he stands at the hen-house door and waits until he has been able to mark off every hen, as present and accounted for, before entering the chamber himself. Usually, with much pleased-as-punch quacking…

Despite the fact he is clearly not a chicken (but don’t tell him that!), the rest of the flock have accepted Plucky’s presence with equanimity and good grace. For his part, Plucky is quite content to go on living in his totally deluded state. I envy him that ability. Every night when I go to lock them up I see him huddled up happily amongst all his chicken pals.

Once again, they provide a shining example of interspecies bonding and acceptance of social diversity. Chickens may not be as intelligent as some other birds – crows for one – but flock life has propelled the evolution of bright, adaptable creatures, teaching them how to co-exist peacefully, smooth ruffled feathers, gauge the consequences of their own actions (apart from Motley- Fool Too), manage relationships, care for their young, and share their space.

Chickens may be descended from slow-witted dinosaurs but that doesn’t mean they haven’t adapted to varying circumstances or learnt a few tricks along the way. Happily ensconced in their cooperative colonies, fed and cared for by humans (although I am not sure I would want to be a battery hen), in some ways they are smarter and more tractable then we are…

…