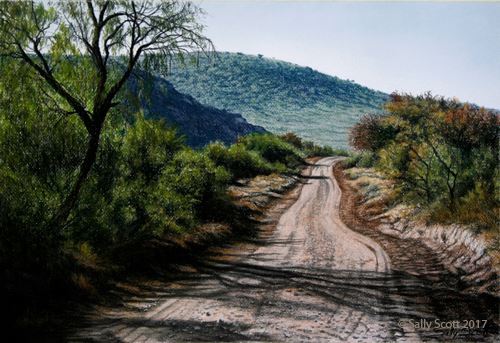

The sun was slanting away behind me sending long thin shadows down the slopes of the Langeberg as I drove past the sign post to Groot Vader’s Bosch.

I had jetted in to Cape Town from Durban that morning on a return pilgrimage to the farm, near Swellendam, where my ancestors, the Moodies, had first settled after their departure from the Orkney Islands, way back in the early 1800s. Ostensibly the purpose of my visit was to celebrate an important milestone birthday in my life with family and friends.

This was not, however, the only object of my journey.

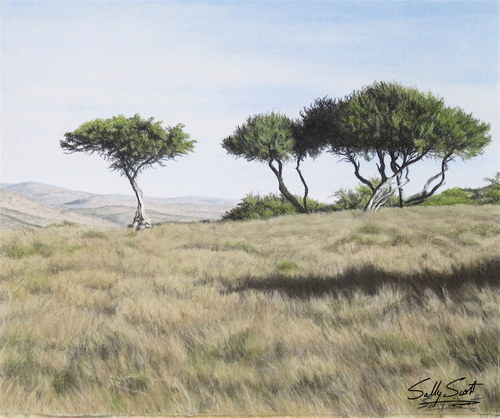

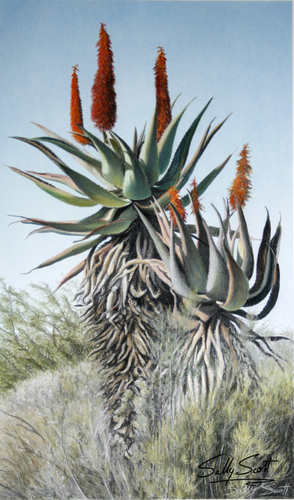

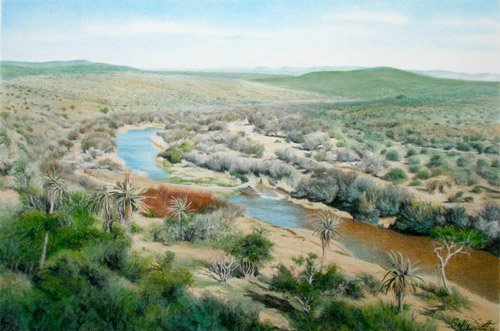

I wanted to know more about the Moodies. I wanted to get a glimpse in to their lives and their thoughts and their feelings. I wanted to experience the sublime landscape they had settled in and try and see it through their eyes as well as my own.

The older I get the more fascinated I become with this stuff. It gives me a link, however tenuous, with my past and a society in some ways like ours, in other respects manifestly different.

I suspect there was another motive too. Maybe it was because, when the whole world seems under threat, it feels comforting to escape backwards.

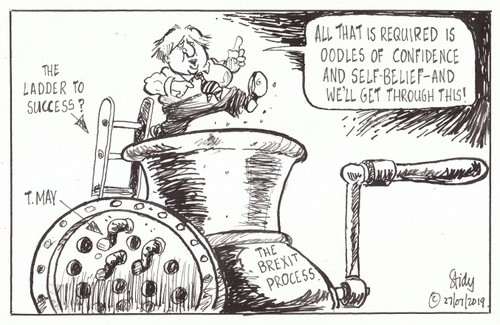

Of course, things were not necessarily any safer or better back in those days. You only have to read any contemporary account of life in nineteenth century South Africa to realise they, too, faced their own peculiar set of challenges.

There were, for example, none of the comforts of modern travel. The sea voyage from Britain to Cape Town was a stomach-churning, gruelling, ordeal in those leaky, old, wooden, wave-tossed, sail boats, especially for those of a delicate constitution. In a letter home, dated August 1775, the Hon. Sophia Pigot (whose daughter would go on to marry an ancestor of mine) wrote “Lud! How weary one grows of salted meat. And of the Ocean too, I swear I am enamoured even of this monstrous queer-shaped Mountain flat as a Board after near four months of nothing but Water on every side”.

And if you were travelling on to India, like Sophia was, you still faced many more exhausting months at sea. The possibility of getting shipwrecked was something else you had to factor in to your calculations…

India was not, however, my area of concern. On this trip I wanted to follow up on a story which I had just scratched the surface of and which involved another ancestor of mine: John Wedderburn Moodie whose arrival in South Africa, exactly 200-years ago, I wanted to celebrate along with my own birthday. Even though I am descended from his elder brother, Benjamin, I have always felt a strange emotional bond with John Wedderburn.

J.W.D.Moodie in old age.

Reading his book, Ten Years in South Africa I kept seeing bits of his character in myself. We even looked vaguely alike. In his struggle to create a new life on the African frontier, I also saw echoes of my parent’s attempts to tame their own wilderness back home in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

Ten Years in South Africa is a delight to read. It is one of those books that appear as fresh and vivid now as on the day it was published. John was a gifted, observant, writer; intelligence and kindness go hand in hand with a keen sense of humour and a sharp – even satirical – eye.The book is full of interesting vignettes and insights in to the South Africa of the time.

While he obviously shared some of the prejudices of his class and era, he seems to have also possessed an instinctive feeling for the other side, displaying an almost anthropological interest in the country and its people which further endeared him to me.

John had originally joined his brother at Groot Vader’s Bosch in 1819. He was clearly taken with his new home among the mountains.

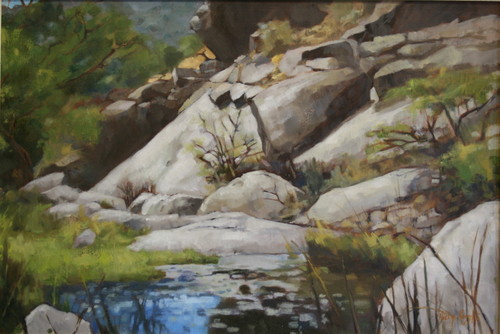

In front of the old, thatched, Dutch-style house, beyond a trim garden shaded by some towering trees, several fields of lush, green pasture-land shelved gently down to a small spruit concealed behind a wild tangle of briers, shrubbery and trees. Upstream the country grew increasingly hilly until, through a narrow cleft, the jagged blue outline of the Langeberg suddenly soared in to view.

Groot Vader’s Bosch homestead.

Upstairs bathroom. Pic courtesy C.Scott.

Kitchen area. Pic courtesy C.Scott.

Kitchen area. Pic courtesy of C.Scott.

John Moodie – owner of next door Honeywood Farm – in main lounge. Pic courtesy of C.Scott.

Benjamin Moodie who originally bought Groot Vader’s Bosch. Pic C.Scott.

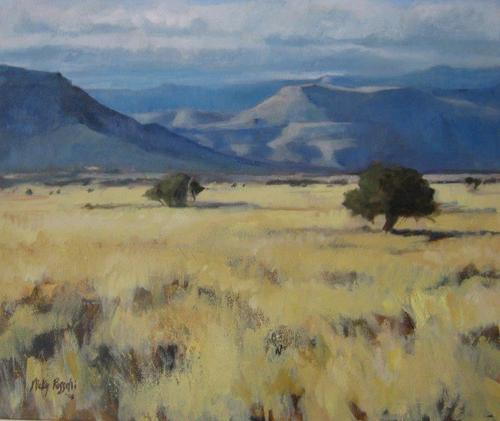

Standing there, the day before my own birthday, I could easily see why the countryside had appealed to a man of John’s romantic sensibilities:

“As may be supposed, amid scenes of such novelty and attraction to a young mind, many weeks elapsed before I felt much disposed to apply myself to any serious occupation. My brother, whose zest for the amusements of the country was renewed from sympathy, and not a little from the pleasure of showing his own proficiency in the language and manners of the colony, cordially entered in to my feelings, and scarcely a day passed that we did not ride out on some shooting excursion among the hills...”

They also paid courtesy calls on some of their Dutch neighbours, including one old Afrikaner towards whom John adapts a teasing, ironic tone:

“Among the neighbours who we visited in the course of our rides in the vicinity of Groot Vader’s Bosch was an old man of the name of Botha. His house stood in a plain surrounded on all sides by high hills; and in front, towards the mountains, a scene met the eye which for wild and savage magnificence could hardly be exceeded in nature…Never was a man less live to the enjoyment of such scenery than Martinus Botha; nor could he conceive what pleasure we experienced in our contemplation. All that he knew or cared for was, that he had a constant run of water for his mill; but whether it came from a romantic chasm, or from a muddy lake, was to him a matter of the greatest indifference.”

Always on the look out for new opportunities, Benjamin and his two brothers would later trek up to the Eastern Frontier. Sir Rufane Donkin, who was Acting-Governor of the Cape in the absence of Lord Charles Somerset, had granted them land in the ceded territory between the Beka and Fish rivers, as well as a stake in the proposed new settlement of Fredericksburg which was to be situated just north of the present day Peddie.

When Somerset returned he took umbrage to these plans which had been made without his blessing and conflicted with his own ideas for the region. He immediately scuppered them.

By way of compensation the Moodie brothers were granted three farms in the Zuurveld, just south of the Bushmen’s River, namely: Long Hope (Benjamin), Kaba and Groot Vlei (John and Donald).

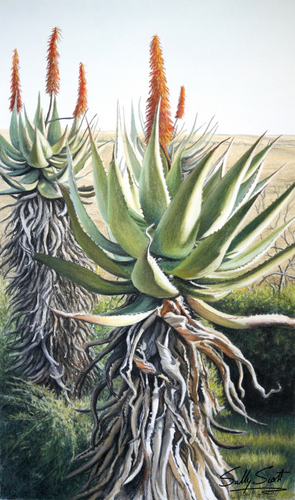

Kaba, the southernmost-property, is situated in a long, cigar-shaped valley which runs diagonally down to the sea. Standing on the apron of land between two hills, the turf as thick and spongy as a tended lawn, the two brothers could not believe their luck at having stumbled on this happy patch of ground. They were quick to appreciate its agricultural worth:

“I have never met with any soil bearing such indisputable tokens of fertility as that of the Kaba, as this alluvial valley is called…” John enthused, “The level bottom was everywhere covered with rich vegetable mould, from one to three feet thick, containing land and sea shells in considerable quantities…Highly delighted with the appearance of this rich but lonely spot, we returned through the wood the same way we came, guiding ourselves by the tracks of our horses.”

Groot Vlei, their other property, lies just to the north of this valley. Running parallel to the coastline between a sheltering ridge of hills on the one side and the large, active, Alexandria dune field on the seaward side, it consists of a series of wave-cut platforms which form a staircase-like feature down to the sea. As the sea-level has dropped relative to the land so the water table has dropped with it, leaving the whole valley dry except during rain.

Because of this problem John and Donald elected to build their home at Kaba which they nostalgically renamed Hoy after the island in the Orkney’s they had come from (it has since reverted to its original name) where there was a more plentiful supply of running water.

For a while the two brothers farmed together but then Donald began to spend more and more time away. The reason for his continued absences soon became apparent. While on a trip inland he had met and fallen in love with Eliza Sophia Pigot, daughter of one of the principal 1820 settlers. The two were married in 1824.

Thereafter Donald gave up farming, making use of his new family connections to secure the position of magistrate and Government Resident at the mouth of the Cowie river. In 1842 he and his family moved to Natal where he entered a career in politics eventually rising to the position of Colonial Secretary under Martin West, Natal’s first Lieutenant-Governor.

With Donald gone, John soldiered on alone first at Kaba and then Groot Vlei, to which he moved because he considered it a healthier spot.

Here he lived what he described as “a kind of Robinson Crusoe-life”. Separated by many miles from his nearest English-speaking neighbours, his farming operations limited by a lack of capital and the distance from the markets, the loneliness eventually got to him. Hungering for companionship he decided to return to England to look for a wife.

In England he met and married Susanna Strickland, one of six daughters in a close-knit, genteel, literary, if not very well-off Suffolk family who could have stepped out of the pages of a Jane Austen novel. With no career prospects in England, John was keen to return to Africa but his new bride had been put off by all his tales of lions, elephants and snakes and so the two eventually opted to settle in Canada, a place where the ever-optimistic John hoped “my exertions will meet with greater success”.

The reality was altogether different.

The most ‘English’ land had already been taken and so they were forced to head further north. The Canada they encountered here, in 1832, was a land of vast, gloomy, almost impenetrable forests broken up by swamps, rocky outcrops and clearings created by forest fires. In its own way it was every bit as wild and lonely as the African bush he had left behind.

The winters were bitterly cold and often the only sound they could hear in the icy dead of night was the howling of wolves. From the start their life was one long, exhausting struggle to survive in a harsh, unforgiving climate.

Susanna’s background, in particular, had hardly prepared her for such a life. She was painfully aware of her own inexperience, she made countless mistakes. Watching her trying to make the best of it, there must have been times when John longingly recalled the magnificent scenery and more agreeable climate of Groot Vader’s Bosch.

Eventually, like other rainbow-chasers before them, the Moodies would abandon the farming life and return to the comparative comforts of the streets.

Susanna Moodie would go on to become a Canadian literary icon. Her book Roughing it in the Bush, which described her experiences in the bleak north, is considered a classic. She and her sister, Catherine, are also the subject of author Charlotte Grey’s double biography Sisters in the Wilderness: The Lives of Susanna Moodie and Catherine Parr Trail which won the 2000 Libris award and became a national best-seller.

Susanna Moodie in later life.

Among Susanna Moodie’s other admirers is Margaret Atwood, the author of a Handmaid’s Tale, who contributed an introduction to the 1986 edition of the book. Placing her with three other women writers, who were the first to produce much of anything resembling literature in Upper Canada, Attwood shrewedly observes that:“If Catherine Par Traill with her imperturbable practicality is what we would like to think we would be under the circumstances, Susanna Moodie is what we secretly suspect we would have been instead.”

Atwood also published a book of poetry, in 1970, titled The Journals of Susanna Moodie in which she adopted the voice of Moodie and attempted to imagine and convey Moodie’s feelings about life in the Canada of her era. It is regarded by many as her most fully realised volume of poetry and one of the great Canadian and feminist epics.

Back in the present, I decided I would pay my own little homage to John and his kin by immersing myself in the water – stained to the colour of a dark, red wine by all the fynbos it had passed through – of the same spruit he had described so lovingly in his book. It was icy cold. One dip and I felt my skin goosepimpling riotously.

I didn’t mind. There was something quite magical about the experience. I felt like I was being baptised in some sort of purifying, healing, sacred pool.

Standing there, shivering, in that hallowed spot, under the lowering majesty of the Langeberg range I felt a special linking of the spirits – that of the land, John Wedderburn’s and mine….

GALLERY:

Some more scenes from Groot Vader’s Bosch:

The Chicken Whisperer calls up the hens of GVB. Pic by Nicky Rosselli.

The Moodie family graveyard.

View from the graveyard to farm below. The old house in on the left, out of picture.

View over the wheatfields towards the Tradouw Pass and the Langeberg. Pic by Craig Scott.

Below are some pics of us celebrating my birthday, as well as the 200th anniversary of the arrival of John Wedderburn Moodie in South Africa. The party was held at Honeywood Farm which adjoins Groot Vader’s Bosch and also belongs to the Moodies. While I was there I managed to spot some unusual birds as well (the theme of the celebration was Birds of a Feather):

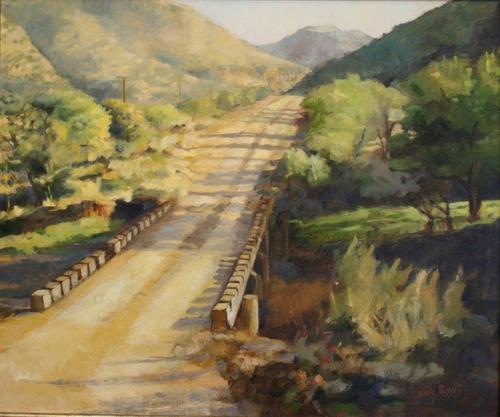

Thinking about the road less travelled. Pic by Craig Scott.

A toast. Pic by Craig Scott.

The twitcher cracks a funny. Pic by Craig Scott.

With my sisters Nicky, Sally and Penny. Pic Craig Scott.

Sullen raptors with cheerful twitcher. Pic by Tammy Scott.

Swooping in for the kill. Pic by Craig Scott.

Some sort of Starling? Or maybe a Sturrock? Pic by Craig Scott.

Blue bird Kelly Bernard and angels. Pic Craig Scott.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Burrows, Edmund H – Overberg Outspan.

Burrows, Edmund H – The Moodies of Melsetter.

Miller, Maskew – Dark Bright Land.

Moodie, John Wedderburn – Ten Years in South Africa.