Every now and again in my life I have found myself in a place that for some mysterious reason exerts a deep, personal pull on me. Such places insinuate their way in to one’s being; my need for them seems to come from the deepest recesses of my unconscious mind. The Nyanga farm, where I grew up, was one. The Zambezi Valley is another…

The first time I went to “The River” was as a very small child, way back in the 1950s. I flew up with my father, an airline pilot, in an old Viking, at a time when the future Kariba Dam was still under construction.

I don’t remember much about that trip other than the fact that the unfinished wall looked like a rash of scabby cement skyscrapers of uneven height sprouting out of the river bed. I also vaguely recall that we travelled downstream to the junction of the Kafue and Zambezi rivers but how we got there I have forgotten.

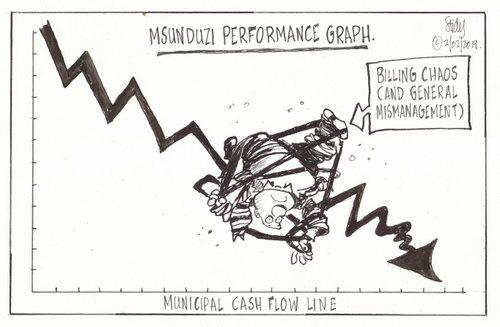

The building of the Kariba Dam wall…two very blurry photos from a blurry period of my life.

Pictures taken from the air by my father, Reg Stidolph, an airline pilot. Note coffer dam.

My next visit was with my brother, Peter, his best friend, Douglas Anderson and Doug’s then girlfriend whose name now escapes me. It was towards the end of the sixties when I was still at university and Pete had just started working as a CONEX officer in Karoi.

My memory of that trip is similarly hazy. I do remember we consumed quite a few beers along the way which might explain that.

I recall driving past the remains of the abandoned sugar mills near Chirundu but am not sure where we actually ended up. I also remember there was only the one shelter which Doug and his girlfriend slept in. Because we considered ourselves rugged, outdoor types, Pete and I just dossed down on a sandbank alongside the river.

Apart from the mosquitoes – tiny, winged, devils in paradise – we slept well enough although we were a little taken alarmed to discover, when we woke up the next morning, that a hippo had walked between our two prostrate forms.

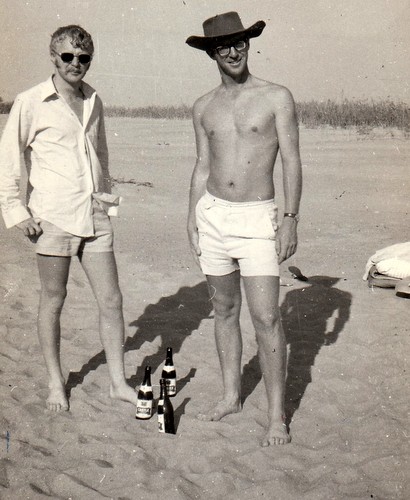

I still have an old black and white photograph of the two of us, taken back then. It is a picture I treasure because it reminds me of more carefree times and captures better than any other our contrasting personalities: Pete – practical, solid, no nonsense, his feet firmly planted in the soil. Me, the future cartoonist, slightly aloof and cynical, a bit of a poser with my sunglasses and ridiculous sideburns.

Standing on that sandbank with my brother, I do remember feeling that there was something that made this place special. I also knew I would return, one day, although, when I finally did so, it was not under the conditions or in the circumstances I desired.

I had left university at the end of 1971 and knew what lay ahead of me – 12 months of National Service. For a whole year I had been possessed by a growing sense of dread and the misery of anticipating the unavoidable.

My fears duly were duly realised. On the 3rd of January, 1973, I found myself conscripted in to the army as a member of Intake 129, “C” Company, the Rhodesia Regiment, based at Kariba.

It was now that I really began to get to know the river.

Our barracks, which had once provided a home for the Italian workers involved in the construction of the dam wall, were situated on top of a high hill – commonly referred to as the ‘Kariba Heights’ – with a panoramic view over the town, harbour and lake below. From here each platoon took it in turns patrolling the gomos ( army slang – from the Shona word for ‘mountains’), the flatlands and the town itself where our duties included guarding the dam wall which linked Rhodesia to Zambia

The gomos are what we called the rugged, inhospitable stretch of country that lie directly below the dam wall where the valley sides close in tightly, squeezing the river into a series of narrow, fast flowing rapids. At the end of the gorge the Zambezi slows down and widens as the land opens up with surprising abruptness into an enormous flood plain (hence army slang: flatlands) while the mountains re-arrange themselves along the horizon, growing further and further apart until finally petering out into nothingness.

For the most part we operated in small, six-man sticks, patrolling up and down the river as far as Chirundu by day and then returning to our base camps – old hunting camps – at night. It was a place of huge heat, a vast sky above and the sound and shimmer of the river below as it snaked its way along the county’s northern border.

At this early stage of the war this section of the Zambezi was still relatively quiet; most of the guerilla incursions were occurring further to the east, across the Mozambique rather than Zambian side of the border. If anything we had more to fear from the abundant wildlife.

At night we could often see and hear hyena lurking around and rooting amongst the rubbish left behind by countless intakes of soldiers before us. Under the cover of darkness hippo would emerge from the river to graze

on the grass that grew along the banks of the river.

Elephant, too, were frequent visitors although usually you could hear their stomachs rumbling long before they got anywhere near you. At other times I used to marvel at what silent creatures they could be and how an entire herd could materialise out of nowhere, as if by magic.

Black Rhino – surely the most cranky, foul–tempered, creatures on this planet (aside from man that is)? – were still relatively common. The sadistic South African helicopter pilots who flew us around used to take cruel delight in making us jump out near them. Because they held rank we couldn’t argue…

As a result, I spent more time retreating from their frontal assaults than I did dodging the other sides’ bullets (although that did change as the war intensified and I got despatched to the “Sharp End”).

Patrolling at night also had its own peculiar risks. There was always the chance of stumbling into herds of silent-standing buffalo concealed in the shadows, their presence usually given away by a sudden swish of a tail or an angry snort. Several large prides of lion also hunted in the area.

Then there were the less visible dangers – tsetse fly, carriers of sleeping-sickness whose bite left a large welt on your skin, ticks, malaria-bearing mosquito and crocodile that lurked below the deceptively placid surface of the river.

At night we each took it in turn to do a stint on guard while the others slept. Strangely enough I learnt to savour such moments. I have never been much good at being one of the crowd, nor did I ever slot comfortably into the highly structured military hierarchy. Guard duty provided me with a brief, merciful respite; the time and silence to be alone with my thoughts, without being interrupted or pestered or ordered about.

Although I was always an extremely reluctant soldier, the army was not all bad. Indeed there were moments of unalloyed magic when it was possible, if only for a while, to forget we were fighting a war.

I loved sitting in the pink afterglow of the sunset, having my final brew-up of the day and watching the river change colour as darkness descended. As the sun sank still further the river and sky became one, the tree line and distant escarpment hanging in suspension between them. It was difficult not to be bewitched by the landscape, the massive, flat valley, the rim of mountains and hills. Often we would be joined, on either side of our position, by large troops of baboon or herds of impala or elephant coming down for their final drink.

Apart from a short period in my youth when I tried to re-imagine myself as a St Francis of Assisi-figure I have never been a particularly religious person but I felt a strong spiritual connection with the place.

Even now, living in a different place, space and time I am still haunted by the grandeur of the Valley.

Since then I have been back to the Valley many times, alternating between Lake Kariba, Mana Pools and Mongwe Fishing Camp, below Chirundu.

At the end of the Rhodesian Bush War, I took my English cousin, Rebecca, then just out of school and waiting to go to Oxford, on an epic road trip around Southern Africa. This included crossing Kariba by ferry and then driving through a mine field to get to Victoria Falls. I don’t think her parents would have so readily consented to the trip had they known about all the skull and crossbones signs and rusty barbed-wire demarcating where the mines were supposed to be.

We couldn’t have picked a better time to see the Falls. Not only was the river flowing at full strength – which meant they were at their magnificent best – but because it was so close to the end of the Rhodesian Bush War the tourist hordes had not yet started returning in their thousands. Prices were cheap, accommodation easy to find (we stayed in the National Park chalets above the Falls) and there were none of the regulations and restrictions controlling movement in and around the main view points that you have now.

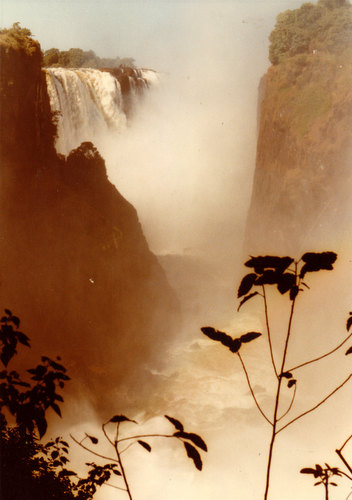

Seeing the Falls after a gap of several years, I was once again overwhelmed by their sheer size and scale. No matter how many pictures you see of them or documentaries you watch, nothing can quite prepare you for the sheer magnitude of this spectacle. It takes your breath away every time.

The one glorious evening Rebecca and I wandered down through the rain forest right up to the edge of the dizzying abyss. Standing there in the drenching spray, watching the never-ending torrent of water hurling down in to the cauldron below – while a orange- yellow full moon rose in to the night sky above it, gilding the water in a luminous glow as it did so – I felt like some would-be mystic. There was something incredibly transcendental about the scene.

What brought the whole experience even closer to the Romantic Age notion of the Sublime (beauty and terror combined) was that we had one of the world’s most awe-inspiring natural spectacles all to ourselves. We were the only ones there.

I doubt if you could do that now.

Kariba Dam wall. Where I once kept the Red Menace at bay…

Lake Kariba.

Victoria Falls – the classic view.

My cousin, Rebecca, on the edge of the abyss, braving the spray from Victoria Falls.

Muso o Tunya -“The smoke that thunders”. I took this pic on the aptly named Flight of the Angels

Victoria Falls – view from near David Livingstone’s statue.

Another trip which sticks out in my mind is when my youngest sister, Nicky, got married. After the wedding, the reception for which was held in Cecil John Rhodes’ old house in Nyanga (now a hotel), we spent an idyllic few days on a houseboat on Kariba before driving on to Mongwe fishing camp. After all the other family members had headed back to Karoi, my companion, Mary-Ann, I and my nephew, James, elected to stay on for a few more days.

The Zambezi is a river which inspires all those who know it well with an infectious passion. James, who farms in Karoi and comes down regularly on fishing trips, is no exception…

As we sped up and down the river in his boat, past sandbars and reed covered islands on which groups of munching buffalo stood, he was full of lurid descriptions of its hazards as well as its attractions. Numerous types of fish swim in it of which the mighty tiger fish is undoubtedly the most famous (James has caught his fair share).

The bird life on the Zambezi is prolific. Its specials including African Skimmer, Lilian’s Lovebird, Livingstone’s Flycatcher, Western Banded Snake-Eagle, Dickinson’s Kestrel, Long-toed Lapwing, Grey-headed Parrot, Thick-billed Cuckoo, Racket-tailed Roller, Collared Palm-Thrush and many more besides.

In the middle of the river James found a shallow shelf where he cut the engine and we all leapt out in to the crystal-clear, cooling, water. Wanting to show I am capable of the odd romantic gesture I re-enacted the whole “Out of Africa” scene, washing Mary-Ann’s dust-coated hair while James, chuckling to himself, kept an eye-out for crocodiles.

My last trip back to the Valley – which was also to attend a wedding (my nephew Alexander Stidolph) – was undoubtedly the most poignant and moving of them all because it happened at a particularly tumultuous and traumatic time in Zimbabwe’s history.

Driving up from Harare Airport the results of President Robert Mugabe’s recent chaotic and often violent land grab had been plain to see. For every surviving homestead, I passed at least a dozen whose occupants had been forced to up stakes and flee. Tobacco barns stood derelict, irrigation equipment and farm machinery lay strewn across the countryside. Uncontrolled bush fires blazed everywhere.

An entire industry, a whole way of life, appeared to be dissolving before my eyes.

Only the Zambezi Valley was as I remembered it.

Dropping down the other side of the escarpment I braked and pulled in to a familiar lay-bye – a favourite pit stop of mine. The air was thick with heat so I cracked open a cold beer and sat there while a pair of Bataleur – still relatively common in these parts – wheeled overhead; dwarfed by the immensity of it all.

For the first time since I started the journey I could feel my jangled city nerves starting to thaw. Sitting under an invincibly sunny sky, listening to the baboon arguing in the rock-faces above and the sound of the long-haulage trucks groaning up the steep incline, I felt I had found my spot in the universe. I was back in my true spiritual home.

I could have lingered there all day, lost in that hypnotic trance, but I had a wedding to get to and ahead of me stretched the long, dusty, rutted track to Mana Pools.

There was something comfortably familiar about the scene that greeted me at the river. Pick-up trucks were backed up in a line alongside the road and under a cluster of trees a makeshift wedding reception area had been cordoned off.

Beyond all the activity, on the river below, a small herd of elephant sloshed through the shallows completely unmoved by all the comings and goings around them.

The next morning I sat out under a huge Natal Mahogany tree and watched the passing parade as the sun rose up over the mighty river. Looking at the scenery and the animals and the myriad of bird-life, I felt I had been let loose among a prodigality of marvels, a feeling made even stronger by the illusion that I had it all to myself.

The wedding ceremony itself was held further upstream, under a large, spreading tree whose branches had conveniently arranged themselves in to the form of a natural altar, through which one could take in the broad sweep of the river and the mountains beyond.

The setting could hardly have been more perfect. Threading his way carefully through pods of dozing hippo, the bridegroom came paddling down the river in a canoe while the bride arrived in a cloud of dust in an old Model T Ford, especially trucked in for the occasion.

Considering how severely depleted the ranks of the local farming community had become there was a surprisingly large turnout although among the guests were many who had lost their farms and livelihoods or joined the great diaspora. Try as I might I found it very difficult to escape the palpable air of sadness, the feeling I was witnessing a last hurrah.

This feeling of loss was made even more acute by the fact I had also come to pay my last respects to my adored brother, Pete, who had died of a brain tumour just days before his farm was seized (my brother, Paul, who farmed nearby also lost his) and whose ashes his wife, Tawny, had placed in an old sausage tree growing on the bank of his favourite section of the river.

As I and the other members of my family gathered around the tree, it occurred to me I was bidding farewell not only to my brother but also the country of my birth.

The memories churned up by this unspeakably beautiful river will, however, continue to flow through my soul until the day I die…