For most of my life, I have lived with uncertainty although I have not always been consciously aware of it.

Indeed, as a child, growing up in a remote part of Rhodesia’s the Eastern Highlands my world seemed as secure as the mountains that surrounded our farm. With a sweat-stained hat on my head, veld skoens on my feet and wearing the regulation khaki shirts and shorts that had got too worn from continual use to take back to school, I would set out in the early morning, a gun cradled in the crook of my arm. In front of me, the farm dogs would range freely back and forth, panting happily. They were not trained to hunt but were still good at flushing out the birds, sending them clattering into the skies, a trail of feathers and bitching noise drifting behind them.

Often I forgot that I had come to shoot, striding cheerfully across the bush through waist-high grass and leaping over rocks and feeling my life ahead of me while all the worlds ‘birds seemed to be calling. Sometimes I would disturb a duiker or startle a small herd of kudu or see a klipspringer peering down at me from some tall pillar of rock but I felt too exulted by their presence to want to put an end to their lives.

I always found the bush a good place to go to when I was upset or needed to sort out my feelings about the world.

Our local radio station and the occasional newspaper we bought did, of course, give us some inkling of the ferment and tensions created by new ideas and awakened hopes but, at that stage, these “troubles” seemed to be confined mainly to the cities and urban areas. Walking on my own across the farm I never felt a moment’s uneasiness.

The fact that I would shortly be witness to the last days of White Rhodesia did not occur to me. Nor did I realise how beleaguered the farming community would soon become, with farmhouses turned into mini-fortresses, equipped with Agric-alerts and surrounded by security fences, while their owners rode around heavily armed over dirt roads that frequently had land-mines buried in them.

The reality of what lay in store would, however, hit home when I received my call-up papers.

My drafting into the Rhodesian Territorial Army on the 3rd January 1972, came at an auspicious moment in the country’s history.

A fortnight earlier, ZANLA forces had launched what would become known as the second chimurenga war (the first being the 1896 Shona uprising against white colonial rule) with an attack on Marc de Borchgrave’s d’Altena farm in the Centenary district during the course of which his nine-year-old daughter, Jane, received a slight wound in the foot.

Although there had been several military incursions in the 1960s from neighbouring Zambia these had been easily dealt with by the Rhodesian Security Forces leading most whites to believe that the country’s small defence force could defeat any conventional invasion or guerilla infiltration.

While hardly a resounding military success in itself, the attack on de Borchgrave’s farm signalled a new phase in the war of liberation, one that saw both a change in direction and a gradual intensification of the conflict. The liberation army had obviously learnt from their previous mistakes. Avoiding direct confrontation with the enemy they now employed classic hit-and-run tactics, attacking white farms, mining dirt roads and going all out to undermine the government’s authority and hold over the tribes’ people.

The growing fears about the country’s security led, in turn, to an increasing militarization of civilian life.

It was my bad luck, too, to be called up for the army (Intake 129) just as the government decided to increase the initial period of service from nine months to one year in response to the growing threat. For me, that extra three months was destined to seem like an eternity.

This was only the beginning. Between 1974 and 1975, the years after I completed my National Service, worked for the District Commissioner’s Office in Wedza and then went to England for a year’s holiday, attacks on whites other than farmers still remained relatively rare. This all changed, however, with the overthrow of the government of Portugal by a junta of disillusioned officers which led, in turn, to a rapid transfer of power in Mozambique, where independence was recognised in 1975. This had the immediate effect of opening up the entire Eastern border of Rhodesia to guerilla infiltration.

Most of this area was mountainous and wild making it extremely difficult to monitor and patrol. As someone who had grown up in the area, I knew only too well, just how difficult it would be to police or stop any groups of heavily-armed soldiers from slipping undetected into the country. Because of its extreme isolation and close proximity to the border, my family made the decision to get my mother off our cattle ranch in Inyanga North, which she was then running all on her own. Although my mother was understandably reluctant to leave, it turned out to be a wise precaution because our only two neighbours were subsequently killed.

Over the following months and years, thousands of insurgents would come pouring over the border in an escalating conflict that saw minds and bodies shattered, and many left dead. I was to discover just how much the situation had changed when I returned home from an extended holiday to England and found myself back in uniform within days of stepping off the plane.

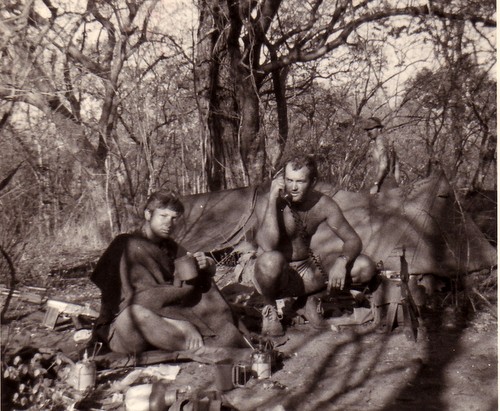

For the purposes of this particular call-up, we were deployed to the Sipolilo (now Guruve) district, a fairly remote farming area that stretched up to the edge of the Zambezi escarpment and which was known to have been heavily infiltrated by ZANLA guerrillas. Arriving at our base camp – an old farmhouse that had been recently abandoned by its occupants after they had been subjected to several attacks – our major wasted little time in sending us into action. At 10 o’clock that night we clambered aboard the waiting convoy of trucks and headed off, under the cover of darkness, into the white commercial farmland. To keep the element of surprise on our side we were dropped off at another deserted farm homestead and then proceeded to march, in single file and as silently as we could, along an old footpath that led us deep into the adjacent Tribal Trust Land.

The track wound up through great blocks of granite fringed with trees and across the dusty stubble of ancient mielie fields. As I walked I tried to empty my mind of everything except what I could see and hear around me. I had no desire to be caught with my defences down. Despite growing fatigue, I was aware of the adrenaline coursing through my body.

Every now and again a breeze would spring up and I would smell the smoke drifting across the veld from countless wood fires. There was something both eerie and beautiful about the night. The moon was vanishing behind the distant hills but everywhere the dogs were barking. High up on a ridge ahead of us we could make out the dim shapes of a group of conical-shaped huts. As we got closer the phantom dogs, picking up our scent, grew more hysterical, breaking into a series of short, angry yelps.

Drawing alongside the hut line, a dark figure suddenly emerged from the central brick building, paused, looked carefully about and then stepped quietly and purposefully towards where we had all ground to a stop. To our collective astonishment, he then proceeded to call out the archaic challenge: “Halt! Who goes there?”

In a different, more chivalrous, age this might have been an appropriate response. In this war, it was signing your own death warrant. Not needing any further prompting we all dived for cover. There was a moment’s silence and then all hell broke loose as the fire of thirty rifles was bought to bear on the sentry who had called our bluff.

As the mass of lead buzzed towards them, a group of dimly lit figures came spilling out of the huts and darted for cover from whence they began to return fire at us. Lying low on the ground I fired off several volleys of my own even though I had nothing clear to aim at.

And then there was silence once more. I gripped my rifle and lifted my head carefully above the grassy verge, on the side of the path, behind which I had tried to conceal myself. I could see no sign of movement. At the platoon commander’s say so we rose and moved forward cautiously, in extended line, through the settlement but it soon became obvious that the enemy had fled. We decided to clear out of the area as quickly as we could and find a good defensive position in case they returned with retribution on their mind.

Floundering around in the impenetrable darkness our stick somehow managed to get detached from the remainder of the group. Realising it would be dangerous to keep moving blindly around we opted to stay put and hide as best we could in the surrounding bush.

Lying half concealed in a grove of trees, my ears tuned to any sounds that might indicate what was out there waiting for us, the cold reality of my situation began to sink in. It was a strange sensation – as if time had suddenly stopped and the past had become as irrelevant as the future. I found it hard to believe that only a week before I had been sitting in the dim-lit, cosy Red Barn pub near South Godstone sipping pints of English bitter, reflecting on how good life was while listening to rock music.

Hoping to provoke a reaction, the guerillas fired off a few mortars in our general direction. After what seemed like an eternity – actually only a few seconds – I heard the flat blap! blap! of their explosions as they landed harmlessly, some distance from where I lay huddled in a ball. Shortly afterwards a machine began to traverse but again it seemed they had no real idea where we were. Not wanting to give away our position, for fear of attracting a more accurate barrage, we refrained from returning fire.

This was to be but the first of several contacts we had over the next six weeks of intense patrolling through this remote, chequerboard landscape of hills and fields and villages. What I saw was enough to convince me that the war had become a whole different ball game from what I had previously experienced and that the insurgents had established a big foothold in the country. I also realised that this was but a warm-up for what lay ahead as we desperately tried to hold the front line. This war was not going to be over any time soon and I knew many similar call-ups and a lot of intense fighting lay ahead…

And so it proved to be.

On the 21st December 1979, the seventh anniversary of the attack on Altena Farm, the end finally came into sight with the signing of the Lancaster House Agreement by all parties. In terms of the agreed-to cease-fire, the Rhodesia security forces were to be confined to their bases while the Patriotic Front was supposed to bring all their forces into the proposed sixteen Assembly Points which would be administered by the British Monitoring Force.

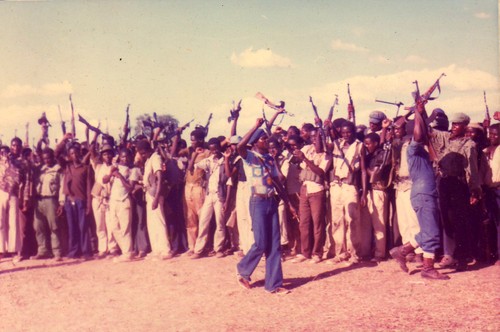

Edgy and distrustful, the guerilla forces, initially at least, showed little inclination to enter their designated AP’s fearing, no doubt, that if they did they would be providing a perfect target for the Rhodesian Air force. For a while it looked like the whole operation might be doomed to failure. Despite the supposed ceasefire attacks on civilian targets also continued.

It was also becoming increasingly obvious that many of those entering the APs were not genuine guerrillas but ‘mujibhas’ (collaborators) and that their more experienced troops had been instructed to remain at large in the countryside

At this crucial point, the British Monitoring Force who had been tasked with ensuring an orderly and peaceful transfer of power suddenly got cold feet and decided to pull their troops out of the Assembly Points. As members of the Rhodesian Territorial Army, we were ordered to step into the breach. In a sense, we were being called upon to supervise our own defeat.

And so, in a final ironic twist, I found myself back at Mary Mount Mission (Assembly Point Charlie) in the extreme North-East corner of Rhodesia, the very place where I had had my first real encounter with the enemy back in 1973– although we had barely got there when we were given orders to redeploy to Assembly Point Alpha at Hoya in the Zambezi Valley.

Close to the Mozambique border, it was an area of intense heat and thick bush. The ZANLA forces already at the Assembly Point had taken good advantage of this, spreading themselves out, no doubt with an eye for both attack and defence, over a wide area. A few of their commanders did set up camp near us but the rest of their troops remained hidden well out of sight. Knowing they were out there somewhere, probably very suspicious and trigger-happy and with their weapons pointed towards us, was not a comforting feeling. To say we were both outnumbered and outgunned would be an understatement – there were over 1 600 ZANLA guerillas and only 26 of us, living under tents supplied by the US Army.

Although on the surface, we were able to establish a sort of peace between us there was no escaping a deeper atmosphere of distrust and hostility. This was hardly surprising considering how long we had fought as bitter enemies. This would lead to several scary incidents – including one when I had an AK47 barrel shoved up against my head by a drug and alcohol-crazed guerilla who threatened to blow my brains out as another soldier and I were escorting him and a group of his unruly comrades down the infamous Alpha Trail. Fortunately, he toppled over backwards and passed out before he could carry out his threat

I can’t say I was sorry when it all came to an end with Robert Mugabe’s victory in the election or that, in spite of winning so many little battles, I had wound up on the losing side. Most soldiers like clarity and in the end it had become increasingly difficult to work out just what we were fighting for or hoping to achieve. I had long ago realised that we just did not have the resources or manpower to contain the conflict. Certainly, the situation on the ground wasn’t improving, in fact, it was getting worse. Nor was it possible for me to convince myself that we held the moral high ground.

I was just glad it was all over and that I had got out of it alive and in one piece. I did not have a coherent plan of what I was going to do with my future. Mostly this was because I had been so deep in the war I had closed my eyes to everything else.

All I knew was that, in the interim, I wanted to go somewhere quiet, a place where the eyes of the world might overlook me. More than anything I wanted a little peace. Bowmont – the small farm near Kadoma where my parents had recently retired to – seemed the ideal fit. For the next four years, I holed up there although my stay would be steeped in sadness because my father would finally succumb to the form of bone cancer that had ravaged his body.

Much as I loved Bowmont I came to realise it was time to close this chapter of my life. And so I joined the general exodus to South Africa, knowing full well that country was also in political turmoil and that I faced an equally uncertain future down there (if I had any sense I would have left the continent but Africa has this way of gnawing itself into your soul). Driving. on my own, down that familiar road through an empty landscape where only a few years before I would have run the risk of being ambushed I found my mind drifting back to the war.

From the very outset, I had had my doubts as to the justness of our cause. Although I could never be sure whether my decision to ignore these niggling feelings was just another form of moral cowardice I had done what was expected of me.

I had stayed on through basic training, I had sweated it out in the “sharp-end”, I had resisted the temptation to stay put in England when I went over on holiday, I had remained (sort of) cool under fire. I had lost a few friends and found a few more. I had discovered how much I could take and still carry on.

I had both endured and survived.

.