It is already early afternoon when I pull over on the top of the Nico Malan Pass, which drops a massive 673 vertical metres over 13,8 kilometres, into 1820 Settler Country. Taking a sip of the now lukewarm coffee in my Thermos, I look at the raw landscape around me. To my right, capped by a bluff of rock, are the Katberg which, in turn, become the Winterberg. To my left, the rest of the mountain chain stretches away toward the Hogsback and the Amatola.

Above me, I can see the pale puff of rain clouds receding over the mountain tops. The very air looks grey and dampness seems to rise up off the tarred road like mist. The road ahead tapers away through miles of dry East Cape thicket, sprinkled with aloes, euphorbia, succulents, sweet thorn, and spekboom..

Although I was not born here, I am, in a sense, back where it began, my home patch. It was here that many of my ancestors settled when they came to South Africa, way back in the early 1800s.

The first was Benjamin Moodie, the Seventh and last Laird of Melsetter in the Orkney Islands whose family fell upon hard times and who sailed from London on the brig Brilliant in March 1817, arriving at the Cape in June. From there he trekked up to Grootvadersbosch in the Overberg where he hoped to recreate his bit of feudal Scotland in the shadows of the Langeberg. It was his grandson, Thomas (Groot Tom) Moodie who led the Moodie Trek into the then Southern Rhodesia which explains how I came to be born and raised up there, among the beautiful Nyanga mountains.

And why I am driving down this road today.

Then there were the Nesbitts (my father’s mother’s side of the family), from Ireland, whose history I have only recently discovered, but whose story I am now trying to follow. Other ancestors too – the Colemans, the Arnotts, the Stirks as well as my immediate kin, the Stidolphs. All spent time in the Eastern Cape area.

As I descend the winding road that leads, through Seymour and Fort Beaufort, into the vast Great Fish River Valley, I feel my senses heightening, flaring. I look and listen, feel the air, try to see the country as they did, all those years ago. Coming from the lush, green pastures of Scotland and Ireland, it certainly must have seemed very different from anything they were used to.

There is an old military blockhouse at Fort Brown, where the modern bridge crosses over the Great Fish River, a reminder of the days when this was all disputed territory. It formed part of a chain of similar forts, strung along the banks of the river, which the British soldiers, garrisoned in them, used to pass messages to one other.

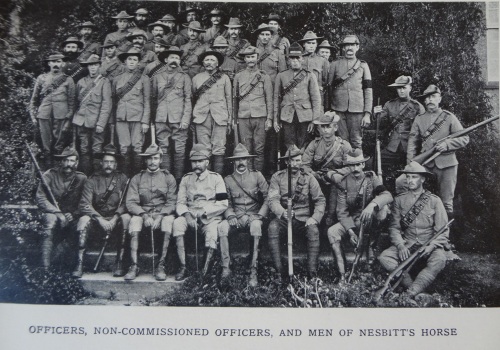

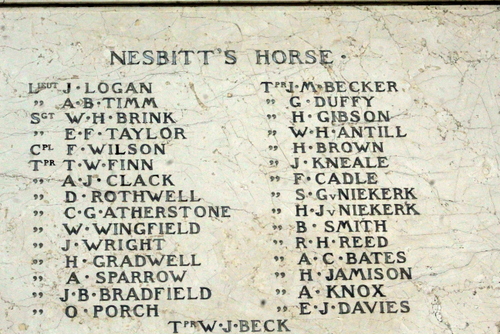

It is here I establish my first connection. An ancestor of mine, on my father’s mother’s side, Lt Col Richard Athol Nesbitt CB, was posted to Fort Brown, as an inspector, in 1875. Later he would go on to form Nesbitt’s Horse which fought with distinction in both the Frontier and Anglo-Boer War. There is a memorial honouring their contribution, among others, to the war effort standing in Church Square, Grahamstown.

Having stopped to snap an obligatory photo of the place, for record purposes, I continue on my way, still taking in the country as I go. Hill leads to hill leads to hill and in between is nothing but space and distance. The oceans my ancestors crossed to get here could hardly have been more solitary than this empty country still is.

It gets me thinking about the 1820 Settlers who settled in this region. Innocent of the reality of Africa, they must have been shocked to discover the arid country, with its harsh climate, they were about to settle on was nothing like the rich farm and pasture land that they had been promised by the propagandists back home. Although the land was theirs to do what they would with, there was another aspect the pamphlet writers had chosen to gloss over in their colourful descriptions– the fact that the settlers were to form part of a Government-approved military buffer zone, aimed at keeping the Xhosa on the other side of the Great Fish River. Inevitably they found themselves caught up in an escalating conflict for which they were mostly ill-prepared.

Perhaps not too surprisingly then, many found it too lonely and too harsh a life and, their faith shaken, put the country behind them to return to the comforts of town life. Others persevered; in some cases, their descendants are still on the same farms. For yet others, Africa proved to be a temporary aberration. Anxious to escape the heat, sweat, and weariness of it all, they packed up and sailed back to England.

For my part, I am bound for Grahamstown where my one sister, Sally, lives. It was here that the settlers decided to build their capital and – because the town never grew at the rate envisaged – you can still see many fine examples of colonial architecture and of their early houses (see Picture Library below). It is also now home to Rhodes University, as well as one of the most dysfunctional and corrupt municipalities in modern South Africa.

The military life seems to have run deep in the Nesbitt blood. Richard’s father, Alexander Nesbitt, had enlisted, at the age 19, in the 67th Regiment (South Hampshire) and was stationed for many years in Mauritius before being sent with the Reserve Battalion, in August 1851, to the Eastern Cape on HMS Hermes to participate in the 8th Xhosa War.

Not much is known about him but his wife occupies her own special spot in history, for she was a passenger on the HMS Birkenhead, which was conveying troops of ten different regiments from Ireland to participate in the Border War when it struck a rock near Danger Point on the Cape Coast and sank with a loss of 450 lives.

The sinking of the HMS Birkenhead is, of course, famous in the annals of maritime history because it was here the order “Women and children first…” originated. Safe in a lifeboat, Elizabeth Anne “Annie” Nesbitt and her third child, the self-same Richard Athol, were two of the only 193 survivors.

Many of the places the various Nesbitts (and there were many of them) had lived in while in the East Cape I have visited myself so I feel I have both set and principal actors. What I now need to do is write a few scenes. For a moment I think of going to the military cemetery in King William’s Town where Alexander Nesbitt lies buried but my time is short and I am not even sure where it is, so, instead I elect to explore the Great Fish River basin from where it crosses the N3 and then take the dirt road that backtracks all the way to Fort Brown – a part of the world that had changed little over time.

With its turbulent, blood-stained, history, the Great Fish has always loomed large in my imagination. Like the Zambezi and Limpopo, it is one of those rivers which has acquired almost mythical status.

The first section of the journey takes you along the crest of a ridge with extensive views on both sides. Although you probably won’t see it mentioned in any tourist brochure, I think it is one of the best drives in all of South Africa because of its wildness, its freedom, it’s feeling of immensity, the land sweeping back in great folds all the way to the distant range of mountains on the one side and the deep blue of Indian Ocean on the other.

Not far from Fraser’s Camp, we turn left off the tar onto a gravel road that runs roughly parallel with the looping river. Many of the place names around here carry echoes of their frontier past. Dropping down into the valley, the first settlement to come into view is Trumpeter’s Drift, one of the many strategically sited forts the British built along the Great Fish in an effort to secure the land south of the river. Unlike most of the others, which stand crumbling and neglected, this solid, block-like structure still forms part of a working farm and is in relatively good nick.

We drive on. Alongside us, the river continues to follow the most circuitous of routes as it twists and turns its way through the landscape. Countless thorn trees swarm together along its banks creating a dense, impenetrable mass. Swollen by the recent unexpectedly good rains, its soup brown water gushes copiously along. Broken branches, old logs, chunks of floating vegetation, and mud sweep past. In places, driftwood is piled high along the banks.

Our next stop is Committees Drift, another military outpost established by the British during the Frontier war of 1819 (the name “committees” is pronounced by locals as “kommetjies” indicating that the origins may be Khoisan or Dutch).

A steel girder bridge, erected in 1887, spans the river at this point. On the other side of it lies former Ciskei, one of the Apartheid government’s grandiose, if ill-conceived, “homeland republics” where the National Party tried to entrench the principle of racial separation. Granted “independence” (but never internationally recognised as such) in 1980 after a rigged election, the idea that it could function as a separate state was, of course, a fantasy that could never work as the South African economy remained dependent on the black workers who lived in remote corners like this. Among the poorest and most neglected areas in South Africa, it was also too small and lacked the resources to ever manage its own affairs and govern itself. It would always be obliged to live in the pocket of its giant neighbour.

We drive on again, passing a group of smartly attired church-goers as we do. I am not particularly religious myself but I rather approve of the fact that there are people who are still prepared to dress up to please their God. A solitary donkey walks along the side of the road with an air of utmost purposefulness as if it has a fixed destination in mind. A herd of goats scurries off as we approach them and force their way through a farm fence. Because of its large size, the ram is unable to get through and is obliged to reverse out. Mustering all the regal dignity he can he strides off, acting like this was all part of the plan.

Ahead, more hills, more flatness while the sun spreads a dry ruddiness everywhere. Occasionally we pass the empty shells of deserted farmhouses, rotting from the top downwards. Eventually, there will be little left to remind you that somebody lived there. Once they stood for Hope in the Future. Now they stand neglected and forlorn, a lonely reminder of the essential sadness and transience of life.

Our plan is to lunch at Double Drift, in the Great Fish River Nature Reserve, another old fort that once housed British troops sent out to Africa to defend the Empire. Completed in 1837, it protected the important route to Fort Willshire and the interior. Although in a rather dilapidated state of repair it, once again, serves as a memorial to a particular moment in South African history.

At the entrance gate to the reserve, we change our mind when we hear how much it will cost us for such a short visit (a substantial increase from when I visited last) so we decide to strike it off our list of Historic Places to Visit and have a tailgate lunch on the side of the road that leads to Kwandwe Private Game Reserve instead.

I don’t need to remind myself what the fort looks like anyway because Sally has done a beautiful painting of it (for more examples of her work see Sally Scott)

Entering Kwandwe, a little later on, I get a glimpse of another challenge the English settlers had to face – elephant. Although long shot out in most parts of the East Cape, they have been reintroduced into some of the larger local reserves, such as Kwandwe. We haven’t gone too far when we see one browsing in the dense thicket, his back stained a dusty yellow ochre from the local soil. A few kilometres on we see another, similarly camouflaged.

Elephants are awesome creatures. There is a mystery, a sense of enchantment, behind their wrinkled grey visage and massive bulk. I can watch them for hours. As intriguing as they are, they do, however, make difficult neighbours to live with, showing scant regard for fences or planted crops or humans for that matter. It is not wise to antagonize them.

On the crest of another ridge, we stop for a final look over the Great Fish River Basin. Below us roll plains, speckled with bush, patterned with cloud shadows, receding into the blue haze of the far mountains, indifferent to man. Once again, I feel overawed by the age and might of this old continent. In such a primaeval wilderness, is very easy to believe here is where all life originated.

By sleuthing around in these backwaters, I also feel I am beginning to get somewhere in establishing a link with my past. My discoveries may not be earth-shattering but they are a start. They provide the building blocks upon which my own life had been constructed.

PHOTO LIBRARY

More pics of forts:

More Fish River Valley scenes:

Grahamstown scenes: