It is a dramatic view in every sense. Directly below the hilltop viewpoint (once an old army base), on which I now stand, the wide-banked, sand-filled Shashe river has its confluence with the legendary Limpopo River, immortalised by Rudyard Kipling in one of his Just So Stories, The Elephant’s Child. In making this union, the two rivers provide a meeting point for the three countries that have provided me with a home, ingrained themselves in my soul and helped shape my life – Zimbabwe, South Africa and Botswana. From there, the now enlarged river runs eastwards through a series of hills and plains, broadening out in places, and narrowing in others. Behind and to the south of me, the land stretches back into the blue haze of the distant ramparts of the Soutspanberg mountain range.

Having paid my nostalgic dues, I make my way back to the car. Overhead a Martial Eagle soars – a huge, unmistakable bird even to the naked eye. The leisure of its circles seems to express a total assurance in its power and domination of the amazing landscape below.

For we are in the heart of Africa.

I fell in love with Mapungubwe the first time I went there. I have always had an interest in archaeology and knew something about the region’s history. I knew that it was home to an important early Southern African kingdom whose trade links stretched to the shores of the Indian Ocean and beyond. I knew that one of South Africa’s most iconic archaeological artefacts – a gold rhino – had been found there. I knew that, for reasons that are still not entirely clear (climate change, exhaustion of resources?), it eventually fell into decline and was supplanted in importance by Great Zimbabwe.

Nothing, however, prepared me for reality.

Situated in the extreme north-west of the country Mapungubwe is a strange but fascinating place where everything seems for me infused with a mysterious significance. Each rock and feature and tree exudes its own peculiar energy. In this magnificent theatre of nature, you can still feel something of the ancient spirit of the continent.

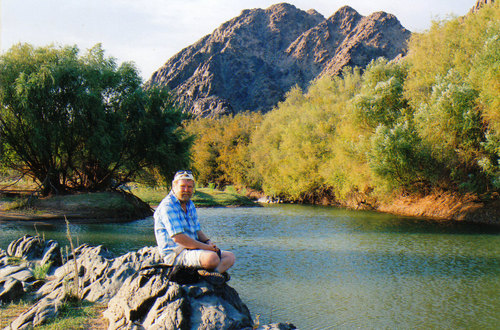

Each time I return – and I have now done so many times – I feel the same stirring of the soul and quickening of the senses. On this trip, I had an added reason for being glad to be back. My sister, who lives in Mpumalanga, had organised a reunion of the four siblings who live in South Africa. Given our mutual love of landscape (three of us are artists, the other a social anthropologist) – and in particular the bushveld – it was the perfect place for such a gathering of the clan.

Much of Mapungubwe’s magic stems from its convergence of habitats, geology and especially its dramatic red sandstone scenery – the rocks which glow like hot embers in the early morning and when the sun sets, only adding to its mythical, otherworldly feel. Stunted mopane dominates much of the landscape. From the Main Entrance Gate, the road passes through a tumbled landscape of heavily eroded and deeply gouged hills. Ghostly Large-Leafed Rock Figs (Ficus abutilfolia) curl around the rocks and send their enormous white roots shooting down through the fissures (hence their other name – rock-splitter figs). Further down, the scuffed and sparse terrain of the hillier parts gives way to rich and luxurious trees that grow along the Limpopo flood plain.

It was here, between 900 and 1300AD, that the kingdom of Mapungubwe was established by Bantu-speaking people who had moved down from the north. It is now widely accepted as being southern Africa’s first state. At its heart was a large sandstone hill, flat-topped and kidney-shaped, with steep cliffs on all sides. Its summit was the exclusive abode of royalty with the commoners living in the surrounding low-lying land. According to Mike Main and Tom Huffman, in their book Palaces of Stone, this separation marked a “dramatic change from traditional ways…now the elite was no longer part of the commoners but physically separated from them”

I had hoped to climb the hill but because I was still recovering from a bout of flu which had badly affected my breathing, I decided not to risk I because of the steep climb involved – although the others did.

Fortunately, my sister had also arranged for us to visit an archaeological dig at an old settlement, that was being supervised by one of her university colleagues, to the south of the Mapungubwe complex. We set off for it the next morning.

To get there, we drove down a rough dirt track crisscrossed with game and elephant tracks and surrounded by a sea of mopane trees out of which rose balancing rocks and oddly-shaped sandstone islands. I saw one that looked like a fossilised terrapin, another that resembled a crocodile and a third which looked like it had swallowed a large fish which now lay there, entombed until the very end of time. Even though it was still mid-winter I could feel a steady thickening of the heat. In front of us, the clouds were piling up like castles in the sky. A great baobab thrust itself up from the earth in front of us, dwarfing all the surrounding trees.

Nestled at the base of a long ridge of stone, entirely hidden from the world, lay the site where a now-vanished people had left their traces in the patches of dry stone walling, clay-lined huts, grain bins and shards of fired pottery. There was evidence of a more recent occupation. For want of decent clay, the swallows that nest under its arch had constructed their nests out of what appeared to be elephant dung.

Watching the team of students laboriously sifting through the sand while keeping an eye out for something which might reveal a tell-tale clue about the past, I got a real whiff of history, a tentative and somewhat blurry outline of how this area must once have been.

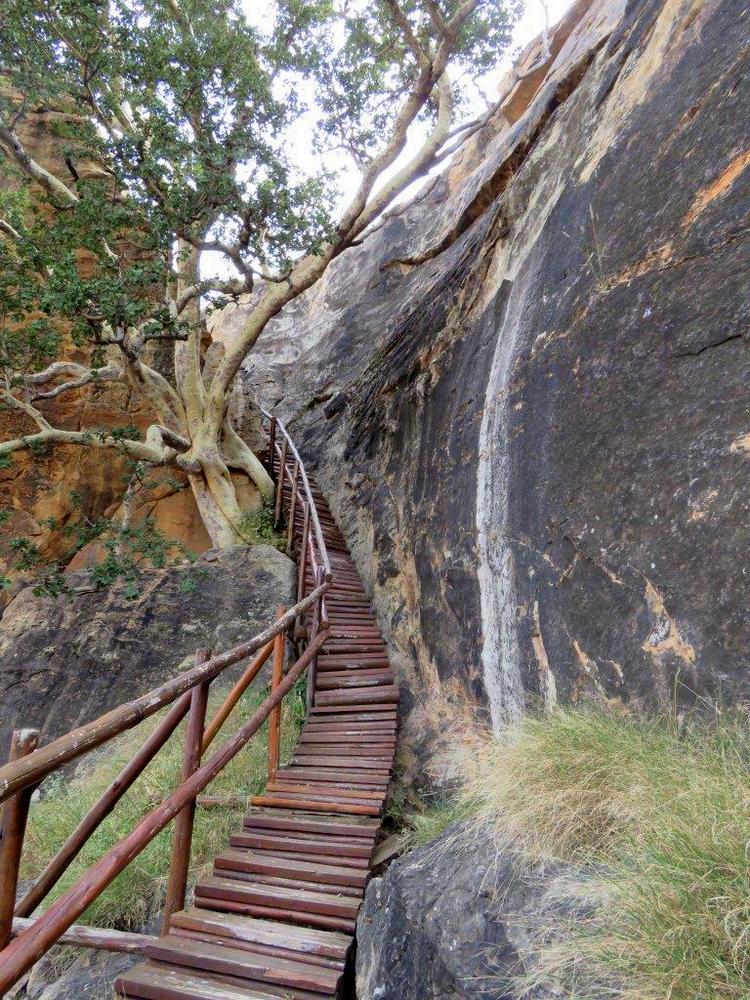

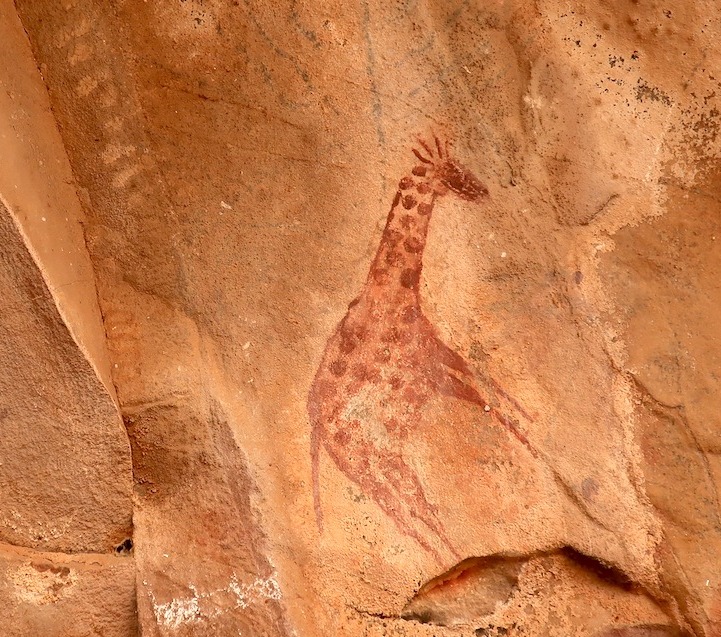

The original inhabitants of South Africa were, of course, the San who had travelled and hunted in this valley in small nomadic bands since time immemorial. Their cultural presence is conserved in the many cave paintings that lie scattered throughout southern Africa. Not far from the dig lies a boulder-strewn canyon which contains some wonderful samples of their rock art.

A hot climb bought us to the ledge under the overhang, also well hidden from the rest of the world, where the paintings are. We stood before them in a line, awed by the artistry. Painted mostly in red ochre, the site contains images of 16 species of animal among its roughly 200 images including rare depictions of locusts, mongoose, spring hare and a hippopotamus. Alive to the constant movements of nature, spirits and human moods, others show supernaturally potent animals and various ritual activities. Some of the paintings are believed to be thousands of years old.

It would be interesting to know how the San reacted to having to share their ancestral ground and what sort of dealings they had with the Bantu-speaking people, one of whose old settlements we had just visited. A fundamental continuity would, presumably, have been the hunting of wild animals although the introduction of cattle into this habitat might well have provided a point of friction, as they competed for valuable grazing. There is some evidence to suggest that the new settlers regarded the San as powerful rain-makers and made use of these skills. In a low rainfall area such as this, it must have been a useful talent to possess.

Hopefully, further archaeological investigation will reveal more about this

What is beyond doubt, however, is that when the first Europeans arrived in Africa they regarded the diminutive race in a very negative light The concept of private property lay outside the world of the San and this, alone, would be enough to condemn them in the eyes of the Europeans, with their clear notions of orderly land use and rational planning. Nor did their mobile lifestyle fit in with European ideas. There were inevitable clashes and confrontations while the “primitive” San’s apparently haphazard and wasteful ways provided justification to stereotype them as ‘savages’ and drive them out and, in other instances, exterminate them.

The treatment of the San provides one of the most shameful footnotes to South African history.

After visiting the cave, I clambered breathlessly up a large nearby boulder-topped kopje that provided a stunning view over the surrounding hills which included several other important archaeological sites – Leokwe Hill, K2, Little Muck – and tried to imagine the landscape as it must once have been when this was still a relatively well-inhabited area.

Then, I did what any sensible twitcher would do in such a situation. I went in search of birds – for Mapungubwe – situated at an environmental crossroad where any bird could turn up -is just as good a place for birding as it is for its cultural history. Although we arrived in winter when all the migrants were away there is still plenty to see. For a start, there are the dry-land specials you don’t get in my neck of the woods – Pied Babbler, Cut-throat Finch, Great Sparrow, White-browed Sparrow-Weaver, Red-billed Buffalo-Weaver, and Chestnut-backed and Grey-backed Sparrow-Lark. In the riverine forest and along the water line you get unusual species such as White-crowned Plover, Maeve’s Starling and – most eagerly sought after of all – the Pel’s Fishing Owl, as well as several predominantly Zimbabwean birds whose territory extends just across the river into South Africa (Tropical Boubou, Meyer’s Parrot, Senegal Coucal and Three-banded Courser – I have seen this relatively uncommon bird twice in the park). This is also great bunting country. Our lodge supported a huge flock of Golden-breasted Buntings who gathered at the swimming pool to drink each morning and evening along with an assortment of doves, Mocking Cliff Chat, Arrow-marked Babbler, Glossy Starling, Striped Kingfisher, Red-headed Weaver, Lesser-masked Weaver, Dark-capped Bulbul and a family of squirrels. Strangely enough, there was also a resident Klaas Cuckoo. It had obviously decided not to join the annual migration northwards (unlike other Cuckoos some Klaas Cuckoos do overwinter).

There was more to be discovered. The next day, I came across both a Red-crested Korhaan and a Kori Bustard, the largest flying bird in the world. In the Western section of the park (Mapungubwe is split into two) a solitary African Hawk Eagle sailed overhead, followed, a bit later, by a flock of White-backed Vultures looking for suitable thermals to take them up still higher into the heavens where it would be easier to spot recent kills. On the drive home, an African Hoopoe floated alongside us. I am always pleased to see them – they are considered to be good omens in some societies, messengers from the gods. I can believe that.

And then there are the animals. Because of its arid climate, Mapungubwe doesn’t support the density of population you get in wetter parks, like Kruger, but they are there to be found if you look for them. As you drive through the park, the heads of giraffes can be spotted. gently swaying above the tree tops, pausing every now and again to nibble on the leaves. A sudden cloud of dust might indicate the direction a herd of Zebra had taken after being spooked by some phantom in the shadows.

At the Maloutswa Hide, we watched a group of warthogs trotting in file down to the water’s edge, followed shortly afterwards by another family. Having checked to ensure there were no predators lurking around, a herd of Wildebeest joined them.

Heading from the hide towards the Mazhou campsite, which lies alongside the Limpopo, we were greeted by a great company of elephants coming out of the woodland. They paid not the slightest heed to our presence as we sat in the car watching their slow-stepping mass crossing the road in front of us, heading towards the denser bush that demarcated the course of the river. The largest cows were on the outer flanks and the bulls and young calves scattered in between. Closer to the river, impala, bright rust red in the falling light, frolicked and scampered over the roots of the massive Nyala Berry trees that are a common feature of the flood plain on which the nearby campsite has been built…

On our final night, my three sisters and I put some drinks in a cool box and drove to a viewpoint, on the crest of a stony ridge, to watch the sun go down over a labyrinth chaos of rock. Apart from the sudden trumpeting of an elephant, somewhere down in the valley below, the magnificent scene that greeted was intimate and peaceful. There seemed no limit to our vision. As it sank through the thin layer of cloud and over a line of jagged hills directly in front of us the dying sun put on a spectacular light show. Except for the birds and animals, it felt like we were all alone in this mythical kingdom. When the air grew cold we came down off the rocks. Although the sun had departed an enormous full moon was shining overhead lighting up the random boulders and ground around us.

I looked and listened, felt the air, and wondered if there is an evolutionary explanation for the deep sense of affinity I feel for this place. Our past is composed of images, experiences, and memories. I knew that someplace around here my ancestors (including my grandmother, then a very young child) crossed the Limpopo by ox wagon on their arduous trek * up to Gazaland in the old Rhodesia. Could this provide another connection?

I was still thinking about all this when we got back into our car and headed home through the dusk…

*Footnote: The wagon train was held up in Macloutsie, on the other side of the river, by foot and mouth disease and many of their cattle became so weak they were devoured alive by the hyaena that prowled around the camp. Thomas Moodie (or “Groot Tom” as he was known) the leader of the trek and brother of my great grandmother, died of blackwater fever within a year of reaching his Promised Land – Melsetter in the Eastern Highlands.

GALLERY:

More Mapungubwe scenery:

More San paintings:

More Mapungubwe birds (and a butterfly and some terrapin):

More Mapungubwe animals:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT:

Palaces of Stone: Uncovering ancient southern African kingdoms by Mike Main & Tom Huffman (Published by Struik Travel and Heritage)