A lone Bateleur, with its short stubby tail and stiffly-held wings, was spiralling lazily in the thermals, as we drove through the Phalaborwa Gate into Kruger National Park. My first bird. I took it as a good omen, a sign that the God, gods, deity, ancestral spirits, shade, cosmic guardian angel or whatever other natural or universal force it is that governs my destiny and gives my life a semblance of direction had given blessing to my latest expedition. Not that I required much convincing. I have yet to go into Kruger – and I have now been many times – and not have a good experience.

The day was overcast and wintry but I soon had several other raptor sightings to scribble down in my battered notebook. Within the space of two hours – the time it took for us to drive from the Gate to our night stop at Mopani – I had ticked off a Brown Snake Eagle, a Martial Eagle, a White-backed Vulture, a Tawny Eagle and an African Hawk Eagle.

The rains had petered out much earlier than usual that summer. It had been a long, dry winter, with higher-than-normal temperatures There was not much surface water and the landscape was bleached and parched, crying out for rain. The dryness didn’t put me off. I can think of nothing more satisfying than driving miles for no other reason than to take in an accumulation of trees, grasses, endless plains, rivers, rocks, animals, birds, ant-heaps, insects, reptiles, sunrises and sunsets. It is a powerful and fundamental experience.

More to the point, I was back in my beloved bushveld. I grew up in a country like this. It wormed into my consciousness when I was still a little boy, became part of my cultural identity, and imprinted on my personality. It is my myth country.

And now here I was once more in familiar territory. I had a pair of binoculars in one hand, and a camera in the other. It wasn’t just good to be back. It felt spectacular.

Once you have crossed the low-level bridge across the Letaba the road begins to veer south. The mixed woodland gives way to Mopani scrubland. It is by far the most dominant tree in the hot lowveld. Where there are mopani trees, you find elephants. Loads of them.

I guess the dominance of the tree provided the rather predictable name for the camp we had booked into for the night – Mopani. We checked in at the reception and then headed to our chalet. The camp was crowded with tourists. Since I consider myself a genuine Bushveld person, I assumed an air of lofty superiority. I wanted them to know I was not of their lowly rank. Keen to put some distance between myself and them, I jumped at my brother-in-law’s suggestion that we drive down to the causeway to watch the sun setting over the dam.

The sky was still grey and overcast when we set off the next morning but as we drove the clouds began to disentangle themselves from one other and slowly drift apart, By afternoon, it had cleared up completely,

Beyond Shingwedzi the mopane veld continued flat, brown and dusty. Many visitors find this section of the road boring because there is seldom much to see and the scenery is so repetitive. My main purpose for going to Kruger is not to record the “Big Five” (although I am happy if I do), I just go to immerse myself in nature. So, I don’t mind driving through this stuff. It is part of Kruger’s charm…

As it turned out, we did see a few interesting things, including a small group of Roan Antelope, at a watering hole. Because of their low numbers (there are only around 100 in the park), they are not often spotted.

We passed the turn-off to Punda Maria camp, built on the slopes of a low, dry hill with Pod Mahogany trees growing on it. Beyond it lie more hills, marking the eastern extreme of the Soutspanberg Mountains. The next landmark is the Klopperfontein Dam built by Stephanus Cecil Rutgart ‘Bvekenya” Barnard, a legendary elephant hunter and poacher who later turned conservationist, as an overnight stopping point and to provide water for the thirsty labourers trudging wearily towards the City of Gold (of which, more later).

The geography started transforming itself before our eyes, breaking up into a wild rocky country. The hills grew closer and larger, and beyond them rose other, steeper, hills. Then we dropped down into the hot Limpopo Valley. Here, the temperatures can hover, in summer, above forty degrees for days on end. Dominating the skyline on either side of the road are huge, ancient, baobabs. The most well-known of these is the one on Baobab Hill, a prominent landmark, just next to the road, rising above its surroundings like an outstretched hand, grasping at the sky. For centuries the hill has served as a prominent beacon and was the first outspan for the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association’s (WNLA but colloquially known as Wenela) route to the Soutspanberg, 1919 – 1937.

Turning off just before the bridge over the Luvuvhu Rives, the dirt road led along the edge of the same river. Its steep banks are multi-coloured and criss-crossed by game paths. Huge trees grow along its sides. Unlike many of Kruger’s other large rivers, the Luvuvhu flows all year around, making it a magnet for all the thirsty animals (and birds) at this time of the year.

In places it opened into glades where the grass, cropped short, was littered with elephant dung. A Ground Hornbill was making his way, methodically, through the piles, picking up balls of it and then tossing them as it went.

At our first pullover, a small herd of eland took mute note of us and carried on drinking. Around the next bend, a family of elephants was funnelling up gallons of water from the sluggish river below. As I stood watching, a bull elephant, perhaps angered by the sound of a rival, emitted an air-splitting scream of agitation and then went thundering through the water, trumpeting loudly as it stormed up the opposite bank.

We stopped at the beautifully shady Pafuri Picnic Site with its magnificent Nyala Berry and Jackalberry trees,

My sister suggested a cup of tea. She got no argument from me. Then, I went looking for birds. Birding is my passion. It is like gaining access to a world that exists parallel to ours, full of amazements and surprises and delights. In next to no time I had seen a Bearded Scrub-Robin, a Red-capped Robin-Chat, a Grey-backed Camaroptera, a Black-throated Wattle-Eye and several other furtive forest dwellers.

Beyond the Picnic Site lie more massive trees that have benefited from the heat, fertile soil and abundant water available to their roots. Some trees are hundreds of years old (the baobabs run to thousands). Every now and again, we pulled over under the leafy branches of these, to see what might be lurking below. When I first visited Pafuri, many years ago, the forest extended even further away from the river than it does now but severe flooding and elephants, with their tree-splitting propensities, have destroyed many of the tall acacia and fever trees that grew along its outer rim.

We reached another intersection and then, turning left, made the short drive to Crook’s Corner, the most northeastern section of the park. Although the Luvuvhu was still flowing, the much larger Limpopo was, at this point anyway, completely dry. Where the two met, a large hippo pod lay asleep on the sand. From their leathery backs, Oxpeckers gazed quizzically about. A pair of White-crowned Plovers – confined to large river systems like this one – kicked up a huge fuss as they swooped angrily over our heads. Maybe they had a nest nearby.

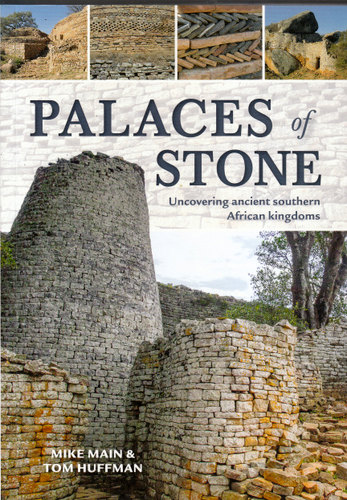

In this harsh country, you really do feel you are on the edge of the frontier, worlds away from anywhere, although, before becoming a park, the area had been traversed and occupied for thousands of years. In venturing deep into the interior, the early traders had followed the river systems, like the Limpopo, exchanging their goods for items such as ivory and gold which they would then take back to the Arab trading stations established along the African shoreline. In response to this burgeoning trade, several important mercantile centres sprung up in the region, of which the most prominent and famous was Mapungubwe, located several hundred kilometres to the west of the park, near the junction of the Shashe and Limpopo (which also happens to form the modern meeting point between South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe). Its capital city was centred around a distinctive, flat-topped hill, on the southern side of the Limpopo, on which lived the king and his more important followers.

For reasons which are still not completely clear the Mapungubwe civilisation collapsed around 1290. Many of its people moved north and east where they joined another iron-age centre that came to be known as Great Zimbabwe.

Between 1450 and 1550 another wealthy trading centre grew up at Thulamela Hill, which is on the right as you leave the main road and turn down towards Crooks Corner. Its inhabitants also established trading links with the Muslim traders at Sofala, in modern-day Mozambique, as well as indigenous settlements in southern and central Africa. You can see why they chose the hill. Strategically located right at the eastern edge of a long line of rocky hills (the direction from which the traders would come), from its summit it provides a miles-wide, panoramic view over the surrounding floodplain.

Later, with the arrival of the white settlers, Crooks Corner gained a more notorious reputation. A big signboard, erected under a large Ana tree, tells you all about it. A well-known stop on the infamous “Ivory Trail “, it became a natural refuge for poachers, illegal black labourer recruiters, gun runners and other scoundrels eager to evade the law. Because it was situated right at the point where three countries meet all they had to do was hop behind the conveniently located border beacon and they were safe from arrest.

On this particular trip the area’s long and, more recently, dubious history was not my main focus of interest. I was in hot pursuit of an unusual vagrant that had caused a bit of a stir in South African birding world circles – the sighting of a lone Collared Palm Thrush at this very location. This bird, with its distinctive black necklace, normally occurs much further to the north, especially along the Zambezi River.

We hunted high and low for it but no luck. Reluctantly concluding that it was not our day for Palm Thrushes, we headed south, out of the belt of riverine forest, to a small group of hills on the one side of which stood the Pafuri Border Post into Mozambique.

Although I had never been here before, I experienced a curious mixture of pleasure, surprise and familiarity when we got there, because the buildings and setting contained so many echoes from my youth.

Even in this Eden-like wilderness, though, one cannot escape South Africa’s fractured past, its old injustices and its history of exploitation.

Regarded, by the new administration, as a symbol of colonial oppression, the one-time Theba Recruitment Station, which was to be our base for the next few nights, had served as a gathering point for Mozambican workers making their way to the gold mines of the Witwatersrand, part of the Wenela labour route. Originally established in 1919 it was finally closed down in 1976, more or less when Frelimo came to power.

I have a connection with its now officially frowned-on history. My father, a professional pilot who, during his forty-odd-year career, had flown all over Africa, had ended up working for the company. He, however, had been based in Francistown in Botswana, flying in labour from the Okavango Delta region, Angola and Malawi – all very far from the spot where I now stood, but the old houses, with their period furniture and room layout, were very similar in design to the one he had lived in, next to the airport. Our residence – formerly “The Doctor’s Residence” – with its wide verandahs built for air, and sun and to help keep the house cool (no air-conditioning in those days) at the height of summer. As an additional protection, it was fully enclosed in gauze, a defence against the malaria-bearing mosquitoes and other undesirable guests who might be out there.

Standing amongst the familiar-looking buildings, I felt the ghosts of my own parents. I remembered our Wenela days, my father, with his lackadaisical stroll, heading home in his uniform, jacket slung over his shoulder, his pilot’s cap slightly cocked on his head, after a long day’s flying. My mother fussing away in the kitchen, preparing a meal for his return.

More fragments from my past. I remembered sitting high up in the air traffic control tower, on the hangar roof, watching the long queues of mine workers, snaking across the runway, heading to or returning from the mines. As exploitive as the system undoubtedly was, there were obvious material benefits for both the workers and the countries they lived in because they invariably returned laden with goods, decked out in fashionable, new clothes and with a lot more cash in their pockets than when they set off to the mines.

That evening I went for a walk. The ground with its covering of crusted leaves crackled underfoot. Outside the perimeter fence, this would, no doubt, make it more difficult for any hunter – man or animal – to stalk its prey. All around me stretched the bush, real bush, vast, unapproachable, moving to its own music, waiting for rain…

The sun, now a bloated orange disc, was sinking through a reddish-gold wash towards the horizon. The trees had still not shed all their summer finery and their water-starved leaves were a kaleidoscope of yellows, oranges and ochres. From our hilly vantage point, they glowed like ambers in the setting sun. All around me, the birds were making their farewell to the day calls.

With the sinking of the sun the bats came swirling out, followed, by a hunting Bat Hawk, burnt black against the western sun. Then, the sky started darkening, disclosing its first stars, and a cool, evening breeze sprang up and helped lift the heavy air.

The next day, we drove back down the same road as we had come in by, scanning the roadside for the Palm-Thrush. It was still playing hard to get.

At Crook’s Corner, the same hippo lay in the same position on the sand (although I was sure they had been active during the night). Not far from where they lay, a solitary Hamerkop stood, motionless, in the shallows, staring intently at its reflection in the water. In local African tradition, the Hamerkop is known as the “Lightning Bird” because it is seen as the herald of a thunderstorm. Maybe the hippo were aware of this association with the supernatural, its slightly sinister reputation in local myth and legend, as a few of them – having resolved to go for a morning dip -, were eyeing it warily, as if worried it might put a spell on them if they proceeded further. The crocodiles were of a less susceptible mind. Several drifted past the feathered narcissist, single-focused, completely unconcerned…

Our disappointment at not finding the Palm Thrush was partly offset, a little later on, by the sighting of a Peregrine Falcon, with its kill, on a stretch of open land on the edge of the forest. Back on the tar, we drove to the Luvuvhu bridge where I hopped out and scanned the river for Spinetail. I have never seen the Mottled Spinetail and this is, reputedly, a good place for them but – like the Palm Thrush and the creature at the heart of Lewis Carrol’s classic nonsense poem, The Hunting of the Snark (“Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice: That alone should encourage the crew.”) – it proved very elusive.

A Raquet-tailed Roller had also been spotted on the road to Pafuri Gate so, with Beaver-like determination, I next went off hunting for it – with an equal lack of success. Such is the nature of birding…

Recrossing the bridge (still no Spinetail) we turned right down the Nyala Loop, at the end of which stands Thulamela Hill. An archaeologist friend, currently working at the site, had offered to take us up (you can’t go unescorted) but unfortunately, his timings didn’t fit in with ours. Instead of exploring the wonders of this ancient kingdom, I had to make do with a troop of baboons, examining each other for fleas on the flat land below the hill.

On the way back home, we made the obligatory detour to Crook’s Corner but the Palm Thrush was still pulling a no-show although a young twitcher, we spoke to, had seen it earlier that day so there was good reason to persevere.

The next day we drove the exact same route, again with a detour to Crook’s Corner, again hoping the find the Palm Thrush. It was becoming a bit of an obsession on my part. I don’t know a great deal about the bird’s habits but they do seem to have a flair for the dramatic because finally, on our last attempt, we found it. It was feeding on the ground, in the company of a pair of Tambourine Doves. At first, all we could see was its back. Then it turned around and with a great flourish presented its chest, putting any doubts we might have had as to its correct identity beyond question! I had found the Snark of Crook’s Corner!

Mission complete, we headed homewards, the next day, through the same landscape, thinned by dryness and dimmed by smoke. Nearing Babalala Picnic Site, we found the responsible culprit – a huge bush fire, pushing up great columns of acrid, grey smoke, was billowing towards us. We had planned a slight detour via the Mphangolo Loop, usually a very rewarding drive with some attractive river scenery. Suspecting it might now be closed to traffic we stopped and asked a ranger. He gave us a thumbs up and flagged us on..

I am not sure who it was who gave them the all-clear sign, but we passed a small herd of elephants, seemingly unconcerned by all the action taking place around the picnic site, trudging towards the waterhole beyond which raged the fire. I love elephants. I love the way they inhabit their space, the relaxed rhythm of their walk, and the pattern and purpose with which they move through the bush. These were no different. They had used this track countless times before and saw no good reason to deviate from it now.

Or maybe they had greater confidence in the firefighter’s ability to contain the blaze than we had shown..

Because the area was so dry. with little water in the rivers. we saw fewer animals than I had on previous trips. In certain places, where it still lay close to the surface, the elephants had dug wells into the sand and were drinking from them. Once they had gone, other creatures would tentatively come down and drink from them too. Most animals are territorial and there appeared to be some sort of dispute going on, at the one well, between a crazy-tailed old Wildebeest and a family of warthogs about who had priority when it came to drinking from it.

When they are not seeing off indignant warthogs, the lone Wildebeest bulls like to station themselves under a shady tree, defending their territory against intruders in the hope of a chance to mate. I’m a Wildebeest fan too.

Driving through Kruger can be a bit like running an obstacle course. True to form, we hit a sudden roadblock – a herd of elephants had found a spot for a good browse and midday snooze and showed no signs of wanting to budge. Our exit route had been barred. It became a game of patience, an old-fashioned stare-down, a test to see who would blink first. We did. After about half an hour of waiting for them to move off the road, we turned the car around and headed back the way we had come until we found a side road leading us back to the tar. Unlike the elephant, we were on a tight schedule.

Back at Mopani. we had booked a chalet with a view over the dam. Instead of going for an evening drive, we chose to sit on its verandah (in my case, beer in hand) and watch the sunset from there. As it sank in the west, it turned the water’s surface a burnished gold. Right on schedule, several waves of Red-billed Quelea swept past, darkening the sky as they went, heading for their nightly roosting sites. On a previous visit, I had actually seen a Bat Hawk swoop into one such flock, seizing the one unlucky bird among the many thousands available to be seized.

As sometimes happens in Kruger, we got our best predator sightings when we thought it was probably too late. ‘On the way out, the next day, we saw, first, a hyena, lying alongside the road. It appeared completely unafraid of us, briefly opening one eye to give us a look over and then going back to sleep. Some people think hyenas are foul creatures, ugly beyond redemption. I am not one of them. I find them quite likeable, almost handsome with their odd, bear-like lope even though, in local belief, these fearsome beasts of the night are often associated with evil. Nature is not a democracy. It operates according to its own rules and as objectionable as some of the hyena’s manners and feeding habits may be to our more refined sensibilities they are just fulfilling their allotted role in the natural order of things.

Then, a bit further on, by the side of a river, we came across a pride of lions who had just finished feasting on a buffalo kill and were now lying sprawled out, belly to the sun. As we sat, the one male rose to his feet and sniffed his female partner’s hindquarters. Then, he raised his shaggy head, flared his teeth and let out an aroused triumphant roar.

One of Africa’s most primordial sounds, it was a fitting finale to our trip…

GALLERY:

Birds:

Animals: