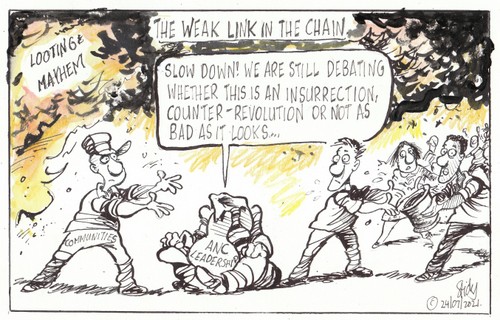

The insurrection or attempted coup or counter-revolution (the various ministers in the ANC defence cluster differed in their interpretation) began on a cool winter’s day in July. Spurred on by cynical ideologists, crowds of supposedly pro- Jacob Zuma loyalists went on the rampage, protesting his recent jailing. Supermarkets and warehouses across Kwa Zulu-Natal and parts of Gauteng were broken into, trashed and ransacked. Everything that could not be taken was destroyed, including the buildings themselves.

For several days after the looting, many shops were still closed, as was the main Jo’burg to Durban freeway. In the absence of effective policing, alarmed communities set up roadblocks in an attempt to protect themselves. Much to my consternation, I found myself having to go out on a night-time patrol, something I hadn’t done since the Rhodesian Bush War days.

It was something I had hoped I would never have to do again too…

From where I sat, on my hilltop home, it all seemed hideously unreal. I felt dazed, finding it hard to believe that almost thirty years after the ending of Apartheid something like this could still happen in South Africa. And yet I was not completely surprised either – given the rampant corruption and mismanagement in the country, as well as the grinding levels of poverty.

Worn out by the never-ending Zuma saga – as well as having our lives upended by the continuing Covid crisis – I found myself longing for an escape.

A chance to get away from it all duly came when my sister, in Mpumalanga, phoned to ask if I would be interested in joining them for a break in Kruger National Park. I said yes. I hoped such a journey would be redemptive. That it would remind me of why, in spite of everything, I still love living in Africa.

And so a week or so later I found myself passing through the Phalaborwa gate and into Kruger. It was good to be back. I suppose it is not surprising that I found the sights and sounds of this place so familiar and comforting since I have visited it countless times before both with my family and my regular birding companion, the sports journalist Ken Borland. I always revel in the sense of freedom and discovery the park gives me which even the occasional discomforts – it can get incredibly hot in summer, the mosquitoes can be a nuisance – cannot detract from.

Familiar and Comforting scenes – Baobab at Mopani…

…Oliphants river.

It is all part of the experience.

Besides its animals and small, biting insects, Kruger is famous for its birds. The variety is bewildering with over 500 species having been recorded, representing roughly 60 per cent of the total for South Africa.

Because it was winter, a time of the year I had never visited the park before, I wasn’t sure what to expect, however. I was immediately reassured. We had not got far into the park when we came across a strangely behaving Spotted Hyena, intently ploughing its way through a small, muddy pan, its nose skimming close to the water’s surface as it went like it was searching for something it had mislaid. I wasn’t sure what that was although, later, I was told that they do sometimes hide the remains of their kills and scavenged carrion underwater.

As we drove on I was rewarded with other happy reunions. I hadn’t anticipated seeing many swallows at this time of the year but as I scanned the sky, above the Letaba bridge, I spotted several beautiful Mosque Swallows – a bird confined mostly to the Kruger area – dipping and soaring over the river. Like the similar water-loving Wire-tailed swallow, they are one of the few swallows that overwinter in South Africa instead of heading north like the rest of their species.

We carried on. Overhead sailed vultures and Bateleur eagle, still relatively common in the park but hardly seen outside it now. In my head I had a sort of hit-list of birds I hoped to encounter and I found myself eyeing each bit of terrain we travelled through, trying to imagine what species might be lurking there. It is not as easy as it seems. Coming from the KZN mist-belt, it always takes me time to readjust to the harsh Bushveld but gradually I felt myself getting my eye and ear in and start to remember how things fit together and relate to one another.

White-backed Vulture

White-backed Vulture

Then I heard a party of Brown-headed parrots, shrieking overhead. Because of their relative rarity (and cheerful personalities), I was keen to locate them. The gaudy birds aren’t as easy to find as you might think, since they always seem to be flying away but these obligingly landed in a tree and started squawking away, giving us plenty of opportunities to study them as they clambered up and down the branches of the trees, playing their parrot games.

Resuming our journey we eventually joined the main tar road, that runs down the centre of Kruger, near the Mooiplaas picnic spot where we stopped for a short tea break. From here we headed north to our first stopover camp, Shingwedzi.

This is very much Mopani country. Stretching as far as the eye can see and farther they are the dominant tree of the northern part of Kruger.

Shingwedzi, itself, is associated first and foremost with elephants and we were to see plenty of these, the largest of mammals, over the next few days. Even when we didn’t see them their impact on the environment was everywhere evident – branches strewn across the roads, entire trees shoved over, paths hammered through the thickets, water holes dug in dry river beds. To the uninitiated eye, the amount of damage the elephant cause may seem shocking but it serves a very useful purpose, reshaping the natural environment for the benefit of other smaller creatures. In this sense, they are regarded as an umbrella species although they require vast tracts of land to maintain their populations.

Elephants on Shingwedzi river

Elephant enjoying a mud bath

Our lodge could hardly have had a more perfect setting. Whereas most of the chalets have, for some reason, been built at some distance from the river our accommodation overlooked it.

View from our lodge

That evening I sat on the river’s edge, sipping a beer and taking in my surroundings as our outside fire sent up its golden fountain of sparks. The light began to fade, the bushes and then the trees on the bank darkened and then got engulfed in the blackness. In the distance, the fiery-necked nightjar started calling. It is a heart-stealing sound, one that captures the very heart and soul of Africa.

Lying in my bed later, I could hear a restless lion roaring from the other side of the river, then, a bit later, the the spooky whooping of a hyena. Not to be upstaged, a convocation of baboons started barking and hurling obscenities from their sleeping positions in the treetops. I wondered what had got them so aroused? Maybe a leopard was on the prowl and they had scented it?

The next morning I woke with a new sense of wonder. The sun appeared. The pale golden tones it cast illuminated the animals drinking at the pool below the lodge, giving them a slightly ghostly appearance. The large troop of baboon that had kicked up such a row the night before now looked completely relaxed as they squatted on the dry river bed, peaceably grooming one other.

Waterbuck

Grooming time.

At moments like this, I felt I could live this sort of life forever.

After a quick cup of coffee to warm us up, my nephew, his wife and I set off along the Red Rocks loop which follows the Shingwedzi upstream to a point where it crosses a band of Gubyane sandstone which has been eroded into a series of potholes. Every birdwatcher enjoys coming across the unexpected so we were understandably delighted to see three Kori Bustard – the heaviest of all flying birds on earth – and then, a little further on, another pair. We also saw – again, the first of several sightings – a Red-crested Korhaan, a bird famous for its peculiar flight display in which the male flies straight upwards, then folds its wings and drops, kamikaze-style, towards the ground, pulling out just before impact.

Kori Bustard

With their big, binocular eyes, distinctive flight, cuddly size and softy, dumpy shape owls have acquired a special mystique and status, figuring in folklore, myths and legends. I love all owls but have a particular affection for the three tiny ones that occur in South Africa – the African Barred Owlet, the African Scops Owl and the Pearl-spotted Owlet. I was as instantly as happy as a lark when my nephew’s wife spotted one of the latter sitting on a deadwood stump, not far from where we had stopped. What makes this particular owl somewhat unusual is that it is often active during the day. Another curious characteristic is that it has a pair of false “eyes” on its nape, presumably to confuse friend and foe alike.

Pearl-spotted Owlet

Red-crested Korhaan

Seeing it immediately made it my Bird of the Day.

After lunch we headed up the tar road to the Babalala picnic site which marks the turn-off point to the Mphongolo River Route, to my mind, one of the best drives in the entire park, taking you through some exceptionally lovely riverine country. As we drove we were met by a dust-devil spinning a plume of red dust, burnt grass and ash. At the picnic site itself, I picked up a Bennet’s Woodpecker which is always nice to get. Plus the usual assortment of picnic site hangers-on: Greater Blue-eared Starlings, Red and Yellow-billed Hornbills and their cousin, the Grey Hornbill. Used to a steady flow of traffic they have become very tame here constantly filching for food.

Yellow-billed Hornbill

Greater Blue-eared Starling

Red-billed Hornbill

You invariably see elephants both here and along the loop. We hadn’t driven for too long when I heard the sombre crack of a branch being snapped and we rounded the bend to find our path barred by a small herd of them. They were feeding on both sides of the road and seemed in no hurry to depart so we had to sit and wait for them to move on. There are also several big herds of buffalo in this area, often carrying both Red and Yellow-billed Oxpeckers on their backs. They are said to be the most aggressive animal in Africa so it always pays to be wary around them.

Redbilled Oxpecker

Yellowbilled Oxpecker

We also saw several giraffes, their heads swaying gently above the trees. They are far less menacing creatures although a kick from one of them could land you in the next world.

The Mphongolo river

The next morning we set off for Mopani, taking the road that winds eastwards along Shingwedzi river to near the point where it cuts through the Lebombo mountains into Mozambique. Huge Jackalberry and Nyala trees lined its banks. Even though we were in the dry season there were still pools of water where wading birds were mirrored, crocodiles lay doggo in the sun and other animals came to slake their thirst. Game trails and hoof prints radiated out from each watering point. The deeper pools had pods of hippo blowing bubbles and snorting into the air.

The Shingwedzi river with impala

Water Dikkop (now Thick-knee)

Wooly-necked Stork

Crocodile lying doggo

The Shingwedzi

At the base of the Lebombo mountains, we said goodbye to the river and turned southwards. Apart from this long low ridge, which provides Kruger with its spine, the low, hot woods around here lack rises or landmarks. Looking across it, as we did from the Nyawutsi viewpoint, halfway up the Lebombo, was like scanning an ocean. On foot, it would be very easy to lose your bearings.

We halted for breakfast at the Nyawutsi hide, a beautiful little glade with a winking, crystal-clear pool, surrounded by Lala palms, Fever Trees and some magnificent old Leadwood and Apple leaf trees.

View from Nyawutsi Hide

Crested Francolin at hide

The scene that greeted us at our next stop, the Grootvlei dam, provided me with one of those spontaneous moments of happiness you only get when you loosen the bonds that tie you to civilisation and escape into the wilds. A small herd of elephants were swimming. Elephants form complex social bonds and language structures and there was ample evidence of this in their playful behaviour here. There was much good-natured jostling and sparring as they splashed around, spraying one another and rolling in the water.

As we watched them another, bigger, herd of elephants loomed through the trees on the other side of the dam, ears flapping, trunks waving, dwarfing the scrub and deadwood. A few minutes later, an even larger herd came lumbering out from a slightly different angle. It was a splendid sight. With all the comings and goings, I felt like I had been given a free front-row pass to some grandiloquent parade, a mesmerising piece of outdoor theatre.

Time was not on our side so having lingered as long as we could we pushed on south past small companies of zebra and wildebeest and even some tsessebe who took mute note of us. We continued to see elephants everywhere.

A g’nother, g’nother, g’nother gnu (wildebeest)

Wildebeest

At Mopani, I was pleased to find we had been allocated the same chalet as last time. The view from it, across the Pioneer dam, was just as beautiful as I remembered. At sunset, the air became completely still and the water turned to gold, perfectly reflecting the dead trees that studded its surface, as well as the surrounding greenery. White-faced Whistling Ducks whistled to one other as they flew off to their sleeping quarters, Great White Egret flapped across the water with thick wings and guttural protests. Huge flocks of Red-billed Quelea landed in the trees below us, weighing down the branches as they did so while chattering non-stop. All around us bats flitted off to meet the dark.

Sunset over Pioneer Dam

Egyptian Geese, Pioneer Dam

Elephant, Pioneer Dam

Great White Egret, Pioneer Dam

I scanned the darkening sky for signs of the elusive Bat Hawk but didn’t see any this time.

The next day we explored the S49 and S50 and the various loops along the Tsendze river, before driving down to the drift at the bottom of the Pioneer dam. In the past this has always proved a happy hunting ground for me and, sure enough, I quickly spotted a Green-backed (or Striated) Heron hunched up over a small pool, a study in single-minded focus and concentration. A few hippos rose and sank in the pool on the other side of the drift. On the far bank, a large crocodile sunned itself. Two Water Dikkop (now Thick-knee. I prefer the old name) stood just behind it, totally unconcerned by its ominous, cadaverous presence. Another large crocodile was swimming just beyond the hippo, with only its snout, eyes and a few ridges along its back visible.

Water Dikkop with croc

Hippo

Having exhausted the drifts possibilities we drove on towards the Staplekop dam. A few small kopjes inset with elephant-coloured boulders rose out of the flat mopane veld. The one, which has a huge baobab growing out of its side, I once did a painting of.

Apart from another Korhaan, skulking on an old airstrip, we saw few birds and not many animals either but that didn’t bother me too much. The fact you don’t have any surprising experiences doesn’t necessarily make the journey an unrewarding one. For my part, I was content just to soak up the sun, heat and stillness of the scene.

What it also means is that when you do finally come across something unexpected you get doubly excited. I was to get proof of that the next morning, on our way out of the park.

We had hit the road and driven south for about an hour when we came to a junction. There seemed to be some animal activity just to the left of it, so we left the tar and crunched down the dirt track for about fifty metres. I couldn’t see what was happening so I stuck my elbow out the window, gazed across the grass stubble and then gasped in amazement. Slinking towards us was a cheetah. Long-legged, streamlined and beautiful, they are an animal built for speed, the fastest in the world. Indifferent to our presence, this magnificent specimen strode disdainfully along, its small head hung low. I was worried I was not going to get any decent shots because it seemed intent on disappearing from view but, at the last moment, it changed its mind and instead of fleeing turned around and leapt up onto the large stone cairn, on the side of the road, that pointed the way to Tsendze Loop.

On top, it struck various poses, like a well-trained model on a ramp, and then – having marked its territory – leapt down and set off again, with its gaunt gait, across the tar road, still unafraid, still searching. It came to a stop at the opposing cairn on the other side of the road, peering around from behind it, as if inviting us to partake in a game of hide-and-seek. It sat there for a few more minutes and then, losing interest, strode off without looking back and got swallowed up by the encircling bush.

I am not normally given to religious flights of fancy but it was hard not to believe that the whole trip had been divinely arranged to lead up to this point. It was a moment of pure elation, one to savour and rejoice in. I may have not got any new ticks for my bird list but I had found a cheetah and, with it, salvation of sorts.

Nor was that the end of it. A little further on, as we were approaching Satara, we came across a pride of lions lazing in the long grass. Unlike the more solitary leopard, lions are social animals and this lot looked especially relaxed and happy in each other’s company although should a rival male appear I imagined the mood would swiftly change and there would be much snarling and gnashing of teeth. And maybe a rather brutal fight.

I would have been quite content for that to be my last big sighting but then, a few hundred metres on, we came upon a small group of those most lugubrious of birds, the Ground Hornbill, waddling across the veld in search of food while cautiously observing us through long eyelashes.

Here’s the funny thing though. I am convinced one of them winked at me, as if to say – see, miracles do happen, especially here in the Bushveld!

As we drove away, I found myself nodding in agreement…

GALLERY

More Kruger scenes:

Red Rocks, Shingwedzi River

Shingwedzi river with Swainson’s Spurfowl

Pioneer Dam, Mopani

Oliphants river from bridge

Oliphants River with hippo, from viewpoint

Countryside near Orpen

More birds:

Burchell’s Coucal

Swainson’s Spurfowl

White-fronted Bee-eater

White-browed Robin-chat

Green Wood Hoopoe (formerly Red-billed)

Green-winged Pytilia

Rattling Cisticola

Double-banded Sandgrouse

Giant Kingfisher with fish (tilapia)

Saddle-billed Stork and Egyptian Geese

Sabota Lark

Water Dikkop (now Thick-knee)

African Jacana

African Jacana

Red-capped Robin-chat

Hamerkop

Marabou Stork

African Hawk Eagle

Burchell’s Starling

More animals:

African Elephants

Sharp’s Grysbok

African Buffalo

Scrub Hare

Tree Squirrel

Hippopotamus

Black-backed Jackal

Wildebeest siesta time

African Elephants on the march

And a few butterflies:

Sulphur Orange Tip, Shingwedzi

African Migrant, Mopani

Sulphur Orange Tips, Shingwedzi

Queen Purple Tip, Shingwedzi

Yellow Pansy, Mopani