I have often wondered what it is that attracts one to a particular place? Why one would feel such a deep connection to it but not feel the same connectedness to somewhere else, even though it is an equally beautiful spot. How and where do these sensual tastes generate themselves? Like one’s attraction to a particular woman, it is not easy to explain – and perhaps it is best it remains that way – although, in my case, I suspect it may have something to do with the farm where I grew up.

The farm, which my father was determined to bully into productiveness (it had sat, virtually unused, since the original Dutch settlers, who had been granted the land by Cecil Rhodes, had abandoned it many years before) was situated at the northern end of the Nyanga valley, just where the European-designated farmland gave way to Tribal Trust Land. The first few years on the farm were, accordingly, spent erecting fences, clearing bush, digging furrows, cultivating the land and erecting buildings. During my school holidays – when I was not being roped into helping with all of this – I set about familiarising myself with my surroundings.

Towering above our end of the valley, the great brooding presence of Mount Muozi rose sharply. Behind it lay the main Nyanga range which was connected to it by a saddle. Back then, no one lived in this mountain fastness. In my youth, I liked to explore these mountains (and the plains and kopjes below). I loved the sense of freedom and discovery that came with it, knowing I was alone in a place where hardly anyone had set foot in years. As you climbed upwards, the terrain and flora began to change, becoming less African, almost Alpine. There were springs, mountain pools, waterfalls and rocky cascades. Sometimes I stripped off my clothes and plunged into these or simply scooped my hands down in it to have a drink. It was cold, crisp, clear and tasted wonderful. Coming straight out of the mountain you did not run the risk of contracting bilharzia, the debilitating disease that required long and tiresome treatment and was – and still is – the scourge of so many rivers and dams in Africa.

Refreshed, I would continue my climb. Patches of forests and glades of trees clung to the more protected spots; eagles, hawks, kites, falcons and kestrels circled overhead. There were kudu, duiker and klipspringer that would stand outlined on the crest of the big boulders, regarding this odd, blond-haired, fair-skinned intruder with curious eyes before bounding away. Leopards still lived in the mountains. I never saw one but they did occasionally come down from their lofty lookout points to kill the odd calf (one actually mauled the elderly black caretaker on the next farm, Somershoek, He survived, thanks to the intervention, with an axe. of his equally elderly wife but he was never quite the same afterwards).

Shrouded in legend and mystery, no matter where you went on the farm, you could never quite escape Muozi’s magnetic pull. It always seemed to be there, hovering watchfully on the horizon, inviting attention to itself, like some ancient giant turned to stone. Shreds of cumulus cloud hung around its summit, as if they, too, had been summoned by its unseen inner denizens. It is little wonder that the mountain played such an important role in the local inhabitants’ religious and spiritual beliefs and was considered a powerful rain-making site.

There is only one stony track, which, after a hot climb, will bring you to the summit. On the flat plateau, atop the soaring rock, where the winds howl, the mists gather and lightning strikes, are the lichen-stained remains of many old clay pots and other detritus – reminders that this is hallowed ground where offerings to the spirits of the mountain in exchange for rain, were (and I suspect still are) made. The view from the top is breathtaking. Down below the country rolls away seemingly endless, patterned with shadows, shimmering with heat, until it eventually merges into the distant blue haze.

Our farm lay directly beneath Muozi. The northernmost section (Wheatlands and Barrydale) was covered mostly with treeless vleis and waving grassland that glowed gold in the late afternoon sun. Elsewhere it changed gradually to woodland out of which the odd baobab thrust itself, bulbous and ancient – who knows how much history they had witnessed? Many of them must have been fully grown when the area’s earlier inhabitants had arrived for, in many cases, they had been incorporated into their stone walls.

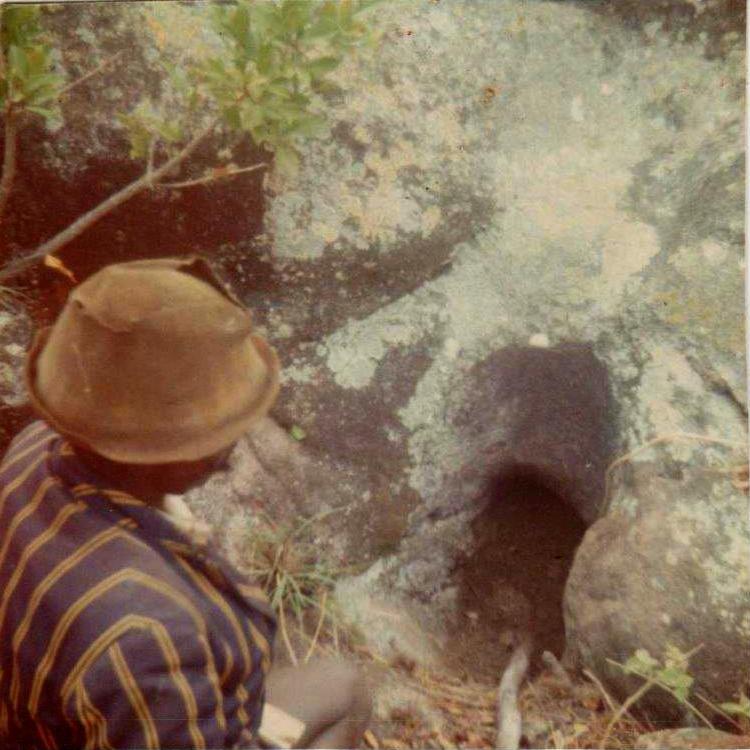

At the base of the mountain, we discovered a hole, with a large rock wedged into its entrance, bored into a solid slab of rock. What purpose it had served, how deep it went, when and how it had been made and by whom we had no idea. A hive of bees had now made it their home. This was but one of the mountain’s many enigmas.

There were also terraces along the entire mountain range, row after row after row, ascending upwards to the uppermost ramparts. Covering thousands and thousands of kilometres, these terraces are considered to be one of the largest and most impressive concentrations of stone structures in Africa. Further evidence of this vast agricultural complex – which dates from the 14th to early 19th century – can be found in the innumerable lined pit structures, hill-top fort settlements, stoned-wall enclosures and track-ways that dot the area. Although a fair amount of research had been conducted on the uplands sites and around the Ziwa/Nyahowe complex, the extensive ruins in our area had been scarcely touched by the archaeologists. I imagine that is probably still the case today.

The locals, we spoke to, seemed to know very little about their origins and so – in the absence of any other evidence (although my father did later obtain a copy of Roger Summers’s Inyanga, Prehistoric Settlements in Southern Rhodesia, considered a ground-breaking book on the subject at the time) – I had a lot of youthful, unscientific, fun trying to imagine who the vanished race was who had built them? My mind still uncluttered by the matter of reason, I would clamber along the fort walls, stare through the loopholes, and let my imagination run unhindered and free, picturing spear-waving armies sweeping across the veld while the anxious defenders huddled inside the walls.

I was not the only member of the family to be intrigued by the archaeology of the region. In my elder brother Paul’s case, it would become an all-consuming, lifelong passion which would see him travelling the length and breadth of modern-day Zimbabwe, searching for little-known ruins and other places of historical interest.

There was, indeed, something wonderfully mystical about the whole Nyanga North landscape. On the western side of the farm, the geology changed, the solid bank of the eastern mountain wall replaced by a mass of granite “dwalas” (of which Mt Nani, which lay between our farm and the Ruenya River, and Mt Dombo, on the other side of the Nyangombe River, are probably the most striking examples although there were many more), mountains, hills and kopjes that seemed to tumble haphazardly on forever. There were San paintings in some of them; for some reason, they occurred mostly on the west of the Nyangombe (or so Paul had deduced).

The rains usually arrived towards the end of October. Each day soaring thunderclouds would gather on the horizon and the wind would fling dead leaves and wild grasses at us as we scurried for shelter. The cattle would grow restless, sniffing the air in anxious anticipation. Often, the huge build-up would peter out into nothing but every now and again the malevolence of the heavy air would be shattered by a bolt of lightning, followed by a roll of thunder and huge drops of welcome rain would come pelting down on our corrugated iron roof. The din would often be so loud we could barely hear ourselves speak.

By the end of March, the rains had waned, and the grass become dry and dead. Wildfires scoured the countryside, leaving behind heavy plumes of smoke that half-obscured the valley. At night, their flickering flames created meandering, zigzag patterns on the mountainside and winked at you in in the dark.

Lying in my bed at night, reading, a small tongue of candlelight quivering quietly on the table next to me, the wind would, on weekends, bring a chant and the thump of drums from our worker’s huts across the other side of the main Nyanga to Katerere road (a sound, unfortunately, you seldom hear today). Schooled, from the earliest age, in the modes of European thought, the spirit world, which they were summoning up, was a place I could never really access but the rhythmic pounding of the drums still exerted a strange fascination over me. At times like this, I realised I would never fully understand Africa on the level they did.

The night was alive with other furtive calls and noises. Owls hooted from the trees, and from various points around the house, came the plaintive, quavering call (usually rendered as “good lord deliiiiiver us,,,”)of the Fiery-necked Nightjar, surely one of the most iconic sounds of the African night which touches a depth in me virtually no other bird call can. Concealed from sight, the crickets chirruped out their messages in stuttering cricket Morse code. From the reed-fringed edges of the weir below our house, a motley assortment of croaking frogs vibrated their nightly courtship serenades. In the moonlight, the horizon would occasionally be crossed by the cringing, bear-like silhouette of a hyena with its bone-chilling howl. It was easy to believe the widely held superstition that witches rode on their backs and sometimes even took their form.

Every now and again, the dogs would rush out barking in the dark at what they perceived to be the threatening noise of a potential intruder. On one occasion, this turned out to be a massive python which had slithered up from the reed-beds and had coiled itself around one of our geese and was proceeding to squeeze the life out of it. The rest of the flock had retreated into the corner of the run, cursing and cackling furiously at this unwanted intrusion into their private goose space.

This, then, was my boyhood domain, my fiefdom. Over time, the farm and its environs became more and more my refuge. Its wide open spaces and emptiness provided an escape, if only a temporary one, from the conventions, the restrictions and the monotonous routines of boarding school life. I think that is why I never invited any of my school friends to stay there. It would have felt like an invasion, an intrusion into my richly imagined, intensely private world.

It was – and, in a sense, still remains – a sacred place for me. I have never again felt such a connection with a landscape, even though it could be a little frightening at times. There was an otherness about it, a sense of mystery. Its beauty imprinted itself on my brain, became part of my psychic makeup, helped shape my personality and profoundly influenced the way I came to see the world. Equally important, it taught me about the redemptive power of nature.

Part of my father’s vision, when he bought the farm, had been that his sons would, one day. inherit and work the land but that was never to be. Like many other whites, we failed to read the writing on the wall. We didn’t fully appreciate we were living at the tail-end of an era. Just over a decade later, the whole country would become plunged into a vicious Bush War. With guerilla forces pouring over the Mozambique border, our isolated farm became an all too obvious target; we had little alternative but to abandon it to its fate or face the dire consequences. In the short-lived Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, it became part of a black resettlement scheme. We were amongst the fortunate few who received some compensation for our loss. When Robert Mugabe subsequently came to power he just seized the white-owned farms, under the pretext he was liberating them for the “povo” (people), but, in reality, he mostly parcelled them out amongst his corrupt senior cronies and cohorts, a reward for their participation in The Struggle.

In an eerie coincidence, my brother Pete happened to be on army patrol in the adjacent tribal lands when he received a report that our empty house had been attacked by a guerilla force, the night before, and reduced to a smouldering rubble.

Later, I would come to realise, that when those rockets exploded into the walls of our much-loved home where we had all spent so many happy times, the innocent world of my childhood had ended. I also knew that I would never live there again.

I often wonder if my subsequent restless quests and wanderings, searching for scenes and places that provoke a similar passion, the same intense love, do not form part of my grieving for this lost landscape of my youth?