I sometimes think that when I travel what I am really looking for is proof that the world is at varied as I want it to be. That is certainly the case when I drive between my home in Kwa Zulu-Natal and Grahamstown, in the East Cape, where my sister, Sally, lives. It is a journey I have made many times and on each occasion I am struck by just how different the two provinces are even though they border on to one another.

Once you get past Queenstown and descend the Nico Malan Pass, near Seymour, an entirely new geography asserts itself.

You are now on the fringes of the Karoo, that immense, dry, sun-scorched, almost mythical, landscape that was once part of a vast, shallow lake. In ancient times all sorts of strange reptilian creatures and other odd-looking beasts roamed this area, thoughtfully leaving their bones behind, embedded in the rocks, for the scientists to study.

The air here is drier, the distances much clearer; the more you travel in to it, the more the sky asserts itself. I can think of nowhere else where it seems so big and blue and empty.

The weather can be extreme, the summers blazing hot, the winters freezing cold. The rainfall is patchy and unreliable and the vegetation has adapted to meet its capriciousness. There are lots of succulents and aloes and squat, low bushes with tiny, tough leaves. Here, almost no tree grows higher than a man’s head except in the mountain valleys and along the river lines.

There is a spirit too, a presence, an unseen power that is very old and has little to do with man. After a while the sheer breadth and weight of the land gets to you. You begin to forget the world you have just come from existed, you can’t help thinking that the whole country looks like this.

The Karoo has the capacity to inspire wonder in all who behold it.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many famous South African writers and artists haled from here. Olive Schreiner, author of the early South African classic, Story of an African Farm, grew up in Cradock. So, too, did the poet and writer Guy Butler.

Thomas Pringle, who came to the Cape as leader of the Scottish party of British settlers of 1820, was allocated land in the valley of the Baviaans River near present-day Bedford. It is still known locally as “Pringle Country”. Eve Palmer who wrote that other classic book about the Karoo, The Plains of Camdeboo, grew up on the farm, Cranemere, down the road from the Bruintjeshoogte and between the towns of Somerset East and Graaf-Reinet. The artist, Walter Battiss, also spent his childhood years in Somerset East (you can see his work in the local gallery dedicated to him).

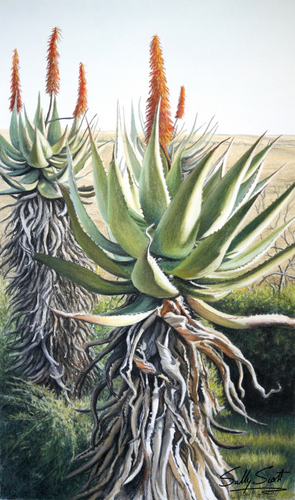

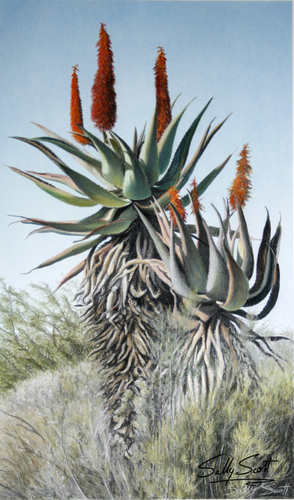

Even members of my own family have found themselves succumbing to the insistent blue skies and lyrical qualities of the Karoo. Sally, an art teacher, has built up a big following with her East Cape landscapes which often have, as their focal point, the aloes which are such a feature of this region. My other, Nicky, also an art teacher, who lived in Somerset East for a while, also felt the urge to record the unchanging strength of the countryside.

How strong this influence has proved can be seen in the examples of their work I have included in the gallery below.

The area around Grahamstown, to which I recently returned, used to be known as the Zuurveld, and later as the Albany district. It is also known as “Settler Country” for it was to this part of the Cape Colony that the early 1820 British settler party came.

To these early settlers this harsh, dry country also marked the beginning of the hinterland, that half-known, half-feared region that stretched endlessly onwards. The further west you travel the wider and emptier it seemed to get. In the far distance stretched ranges of mountains. What lay beyond them was just a rumour, a region of fancy and conjecture.

Even today the land still feels like frontier country, wild and sparsely populated. Far more than in Kwa-Zulu-Natal, where, I come from, you get a real feel of what it must have been like for those early settlers, struggling to eke out a living in these remote and isolated outposts.

In KZN development after development has blighted the province: holiday homes, retirement homes, bungalows, duplexes, massive walled complexes that stretch for miles. Factories belch out smoke, power lines criss-cross the countryside, an endless stream of traffic pours down its main arteries, the urban sprawl and shack-towns seems to grow bigger by the day.

Aside from its coastal areas, you don’t get that feel at all in the East Cape. You can travel for miles through the Karoo without seeing another vehicle. It is like you have the universe all to yourself.

Every time I pass through it, I find myself trying to imagine the feelings of those early arrivals. How alien the harsh landscape must have seemed after the soft green of England.

Many of them must have felt they had been hoodwinked. The pamphlets that had been dangled in front of their faces, back home, promised the prospect of great self-improvement, a land of milk and honey, an amazing opportunity. The reality was completely different with many of them finding themselves stuck in the middle of the no-man’s-land between the white settlers moving north from the Cape and black settlers moving southwards. The Fish River which winds its way through this area was often seen as the dividing line with the British authorities building a line of defensive forts along its banks. In places you can still see the remains of these.

Some settlers stayed on on these outlying farms, braving the dangers and determined to make a go of it; others found the country uninhabitable, packed up their belongings and headed off, blazing a trail of retreat that others would follow.

Every so often you come upon a solitary farmhouse, each one part of a narrow stream of civilization that wound itself through the wilderness. Sometimes there will be a steel wind pump and a circular water tank around which some cattle have listlessly gathered. Mostly, though, this is sheep country.

And goat country. There are lots of goats in the Karoo.

Angora Goats.

Boer Goats.

We did a day trip out of Grahamstown, taking the road, which leads past Table Farm with its wonderful old, double-story settler house and small stone church, and ends up in Riebeek East. Situated in some hilly country, the town – if such it can be called – was founded in 1842 and initially named Riebeek after Jan van Riebeek, one year after the local church was built. It was erected on part of the farm Mooimeisjesfontein that was subdivided and sold by the subsequent Voortrekker leader, Piet Retief. His old home is situated just east of the town and has been declared a national heritage site.

Old Settler home, Table Farm.

Old Church, Table Farm.

As in most small South African dorps, the church dominates the town. When we stopped outside it the only sign of a congregation was a herd of cattle grazing in its grounds. It was a very impressive structure, nevertheless, which seemed far too large and grand for such a sleepy little hamlet.

Church in Riebeek East.

Old settler home, Riebeek East.

Maybe it had once been different around here. Indeed, visiting many of these old Karoo towns, one gets the feeling that at one time they supported much larger populations, especially when the wool industry was in its heyday. With the boom years gone most of the young folk trekked off to the cities and towns.

From Riebeek East we followed the dirt road that eventually leads to the main Port Elizabeth highway although we planned to turn off before that.

To our left, ran a long, low range of hills where you could see how the exposed rock had been buckled and folded, like a carpet you have just shoved with your foot. In front of us the road rose in to crests and sank in to hollows.

Eventually we came to a junction where we branched off down another dirt road leading to the curiously named, Kommadagga. It was a place I was keen to see.

Kommadagga (the name is believed to be Khoekoen meaning “ox land” or “ox hill”) was a small, purpose-built, settlement constructed by the South African Railways, in the early 1950s, to house the workers involved in the construction of the nearby railway line. At the time it had over 1 000 residents, with an elementary school and a recreation hall. Once their work was finished, its population was uprooted and moved further north to the next section of the new railway line.

Now it is a ghost town, its reason for existence long since vanished. The houses are just shells. You can see right through them, the sunlit, empty rooms with their peeling walls; windowless, door-less, their roofs caved in. In places they had broke clean in half, the bricks scattered over the veld.

Old buildings, Kommadagga.

Across the road, a couple of hundred yards away, crowning a low hill is an old water tower and to the side of that some concrete pillars whose former purpose I could not fathom although I imagined it had something to do with the railway line..

We pulled up beside one of the wrecked houses and while Professor Goonie Marsh, our amiable driver, long-time Grateful Dead fan and expert on matters local, fired up his volcano for coffee on the side of the road, I set off to explore. I made my way through the remains of gardens, past rusting fences, auto parts, old cement water storage tanks and all the other scattered detritus that suggested a civilisation of sorts.

There was one house which was in better shape than the rest, an empty wine glass on the verandah wall suggesting it might still be occupied but by whom I had no idea. Near another house there was an outbuilding full of old shoes, in another a collection of goat skulls which got me wondering just how they had passed their time around here.

In such a place, one can imagine there was not much to do. They probably smoked, played cards, drank too much. On Sundays, the more God-fearing among them most likely trekked off to that fine-looking church in nearby Riebeek East.

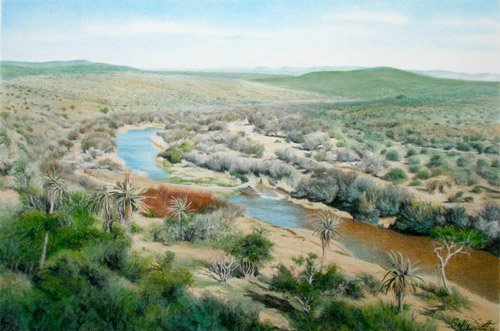

From Kommadagga, we followed the old rail bed until we reached the Kommadagga Station, some distance away, where the railway line and the road diverged. Cresting a rise we found ourselves looking over a vast basin through which the Fish River flowed, its presence marked by a line of trees.

Along its edge a large expanse of land had been cleared and bought under irrigation, the verdant green contrasting sharply with the surrounding dry bush. To the south and the west, glowing in the morning light, the thin, distant, blue outline of the Bosberg rose through the haze.

We drove on, stopping every now and again to take photos of the aloes which grow is such profusion around here. Their candelabra of flowers were aflutter with sunbirds (mostly Malachite and Greater Double-collared with a few Amethyst) – such a bright, fragile, flowering of plants and birds in this hot, dry, khaki and grey landscape.

Out here, one gets the feeling no one seems to be in a hurry. Flocks of lazing sheep gaze at you from underneath the shrubbery. Small groups of cattle pose amongst the aloes, nonchalantly chewing the cud. They give the feel of being completely cut off from the world and not minding a bit.

Sheep with Aloe striata in foreground.

Cow in Aloe ferox.

This, we discovered, was not altogether true. Crime – the curse of modern South Africa – has spread its tentacles even to out here in the boon-docks. When we stopped to take pictures of some sheep, grazing in a field, the local farmer came hurtling up in a cloud of dust with a bakkie full of security guards. He was worried we were rustlers!

Karoo rush hour traffic jam…

Having convinced the farmer we had no ill-intentions, we continued on our way. As we drove the views changed but not suddenly or sharply. Nearing the main Grahamstown to Bedford road more mountains hove in to view – the Winterberg, the Katberg, the Hogsback. Between them and us there was yet another huge, aloe-dotted, plain.

Aloe ferox next to Grahamstown to Bedford road.

Katie finds a view point.

Despite its timeless feel, some things are changing. In this harsh environment, many farmers have discovered that tourists pay better than sheep, cattle and crops. As a result they have started restocking their properties with many of the same game species their ancestors so casually shot out.

Back on the tar I continued to study the ground topology. To me it looked like the worst soil imaginable but the termites obviously liked it because the veld was littered with their pinkish-yellow, nipple-shaped mounds. In between their habitations were yet more flowering aloes full of twittering sunbirds.

Then we were driving back through the outskirts of Grahamstown, past the municipal dump out of which much of the rubbish had been blown and now lay piled up along the side of the road. Or had been left hanging on the fences like some sort of weird, welcome-to-town, decoration.

There had obviously been a big fire in the dump recently, too judging, by its burnt colouring and the pungent smell in the air.

At this point, I found myself wishing we could turn around and head back the way we had just come. Then I remembered I had an appointment at the local craft beer brewery, in the hills outside town, and changed my mind again…

GALLERY:

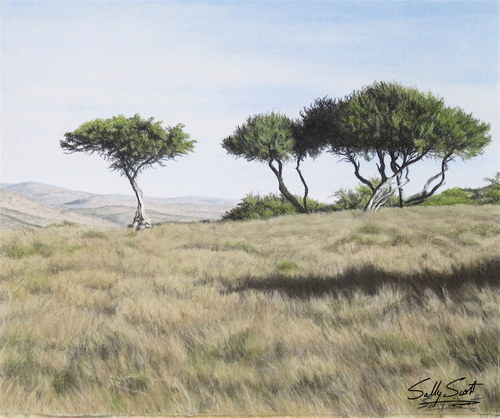

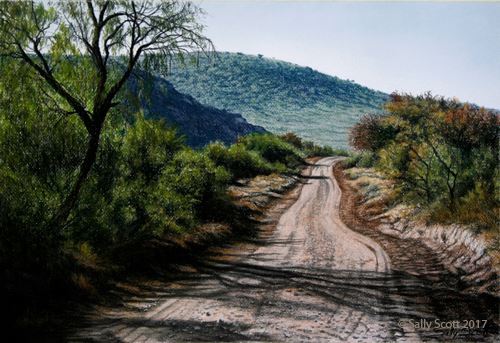

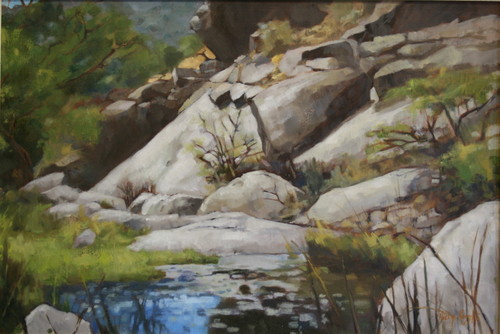

Here are some examples of Sally’s artwork:

Kommadagga.

Asante Sana.

Grasslands.

Ecca Pass.

Cradock Road.

Aloes 1

Aloes 2

Kaboega – Suurberg.

The Fish River.

Table Farm.

The road less travelled.

Viewpoint.

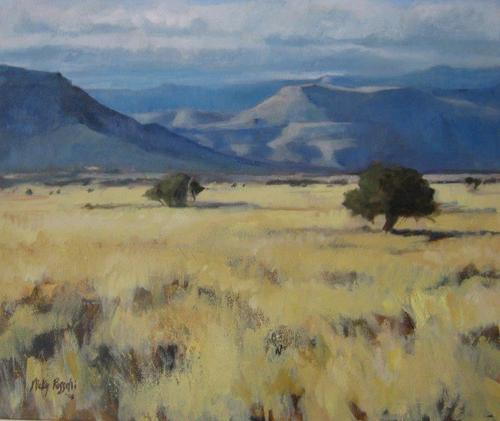

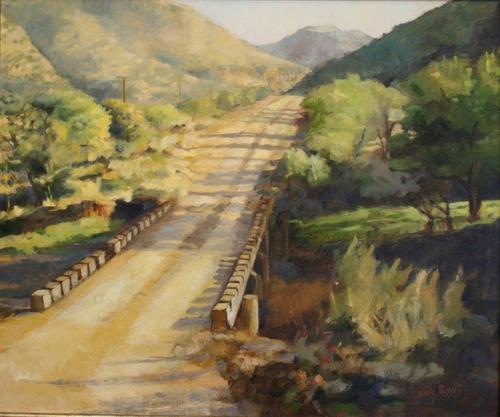

And here are some examples of Nicky’s work:

Dassiekloof – Witmos.

Camdeboo evening.

Bridge over Baviaans River.

Blue mountain – Coetzeeberg.

The Winterberg.

Dirt road, Swaershoek Pass (near Somerset East).

Dorper sheep.

Angora goat.

Brahman bull.

Aloes 1

Aloes 2.

Merino ram.

To see more examples of Sally’s work visit:

Website: www.sallyscott.co.za

Blog: http://sallyscottsart.wordpress.com/

To see more examples of Nicky’s work visit her website: http://www.rosselli.co.za

We were in PE, Cambdeboo, Great Reinet area last month and the the aloes were in full glorious bloom. You description of the wide open spaces and lack of people resonates.

It’s the feeling of leaving the peace and quiet of the midlands of Natal and then ‘ hitting’ the N3.

I managed to find the original Trappist Mission site (1880) , on the Dunbrody Unifrutti farm near Addo. There were remains of the missions church and cemetery at the junction of the White and Sundays river. These structures were built later by the Jesuits.

LikeLike

Thanks, Hugh. It is a great place to go if you want to get your mojo back! Interesting about the mission site – are you planning another book?

LikeLike

Hi Ant,

Working on something at the moment but still a lot of work to do.!!

Regards

H

LikeLike

Very evocative and a great read. So glad you captured in words what was a memorable outing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Nicky. The compnany made the whole experience even more rewarding!

LikeLike

great post Sid and love your sisters’ works

LikeLike

Thanks, Richard. I am a big fan of their work too…

LikeLike

As always Ant, I learn so much from your blogs and the latest one set in the E Cape doesn’t disappoint. Also love the images of Sal and Nicky’s amazing art. And your photos! What I particularly admire are your adventures off the beaten track, a lesson to us all.

LikeLike

Thanks, Gill. As I am sure you know I am always at my happiest when I am off exploring the back roads so it is good to know my descriptions of them are appreciated. It was also nice, in this case, to have an excuse to showcase Sal and Nicky’s art!

LikeLike