If there is one thing lockdown has done it is to force us to redraw the parameters of our lives. Suddenly, everything has shifted, the familiar signposts have been removed, the old sense of continuity has gone. Instead, I am faced with the difficulty of navigating differences over such issues as the wearing of masks, social distancing, how much contact to have with others and whether I can risk eating out?

In short, every decision I make is weighted in moral ambiguity. Cast adrift from my usual moorings, I find myself torn between the need to stay safe and a desire to escape.

It is not the being alone that bothers me so much as having my freedom taken away from me. I have always been happy to embrace solitude provided it was on my terms. With lockdown that has all changed. Now it is being imposed by decree from above with the government taking increasing control over things and placing limits on our movements

While I can understand the need for some of them, being bogged down in this murky mire of regulations has bought out all my anti-authoritarian tendencies, as well as my fear of being trapped. Suddenly it is like I am back at boarding school where all the rules are designed with the naughty boys in mind. For example: because there are quite a few delinquent drinkers in south Africa, a blanket ban is imposed on alcohol sales which means all of us are collectively punished irrespective of own behaviour.

With the pandemic shrinking our horizons, my fear is finding myself confined to a cramped, parochial lifestyle. I worry about sliding in to passivity.

I have always lived a fairly nomadic life, ready to hit the road whenever I have felt that familiar build up of stress and anxiety, like a smoldering fire, inside me. I think this restlessness can be attributed, in part, to a childhood spent among the beautiful Nyanga mountains and a deep-rooted urge to retrieve that part of myself in a far-off place. Also, I like to feel I still have some control over my life. That I am able to exercise my skill in being free.

As lockdown progresses I have found myself fantasising about trips I want to make, as well as recalling some of the ones I have made in the past. I play them over and over again in my imagination, remembering bits I had forgotten.

I pour over my old AA maps planning possible new routes. I formulate plans which will probably never come to fruit. I look at photographs of trips I have made in the past. Because of the circumstance I now find myself in, their memory suddenly seems more precious than ever. There is a sadness too. In some cases the pristine places the photographs have captured are disappearing. Others I will never see again.

It is hard to pick a favourite journey but, if forced to do so, I would probably settle for the Great South African Traverse, I undertook in September, 2003, with my birding partner, Ken, just because of the sheer diversity of countryside we passed through.

Umhlanga Rocks, Indian Ocean. Pic courtesy of Mark Wing.

Alexander Bay, Atlantic Ocean. Note old diamond workings.

Wanting to do it by the book, we started off by dipping our feet in to the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, at Umhlanga Rocks, and then drove across the breadth of South Africa and did the same in the freezing Atlantic, at Alexander Bay. Along the way we stopped at Vaalbos National Park near Kimberley and also at the Augrabies Falls.

Augrabies Gorge.

Vaalbos (near Kimberly).

I had never been to the Northern Cape before but the first thing that struck me about it was how straight and long and empty the roads are. Much of the landscape between Kakamas and Springbok is flat and featureless too but the N17 does take you through Pofadder which is a place I have always wanted to visit because of its quintessential South African name. There is not much to the town apart from all the huge communal nests of Sociable Weavers on either sides of it but I did buy a lump of rose quartz, in the local café, just to prove I had been there. I still have it.

The further west we drove the drier the countryside became and the fewer trees there were until, finally, we entered a landscape that consisted mostly of stones. This was the Richtersveld, South Africa’s only true desert – or rather mountain desert.

Wedged right up in the north-western most corner of the country along the border with Namibia it is a wondrous place, a truly mystical landscape of moulded, multi-coloured, rock and drifting sand. The sky is a strange intense blue, limitless and criss-crossed with lazy scrawls of thin, vaporous, cloud.

Richtersveld scenes.

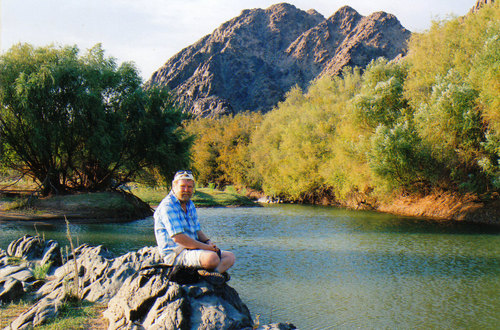

For our first few days we camped at Pokkiespram on the Orange River. It is an enchanting spot with the water idling languidly past while the mountains on either side rise up to naked peaks of rock.

Next on our itinerary was Kokerboomkloof. The road to it was marked on our map as 4X4 only but we decided to risk it in our small blue Ford sedan, heading up through the Helskloofpas – the name should have tipped us off as to what we could expect – in to Tatasberg mountains. We were probably foolish. It is not the sort of country you want to break down in because there is no water, no communications and you never know when the next traveller might chance along.

Also, our spare tyre had a puncture.

The road snaked its way between colossal boulders, around cliffs, ravines and barren gullies until, finally, on the other side, we found ourselves looking out across a vast, pale, plain, that appeared devoid of all vegetation. Along its horizon stretched another range, perhaps even higher that the one we had just crossed. Certainly the peaks seemed steeper and more pronounced and as desolate and devoid of life as anything we had seen. I was obviously not the only one to find them scary and intimidating. Consulting the map, I discovered some early cartographer had named them Mount Terror.

The road skirted the edge of the plain before winding its way up a rock-strewn kloof amongst which grew the strange-looking Kokerbooms – or Quiver Tree – that had given the place its name. Because of all the twists and turns and the numerous humps which, for some reason, had been put across the road our progress continued to be heartbreakingly slow. When we finally reached the top I felt a mixture of relief and exhilaration and was only too happy to stand there, absorbing the silence and sense of solitude.

With its dead, dry, moonscape setting, Kokerboomkloof is as about as far as you can get away from the cooped-up space of the cities. When the night closed in around us, I really did begin to comprehend my own insignificance in the vast scheme of things. Curled up in our sleeping bags under an enormous star-studded sky, you could hear no sound other than the occasional gust of wind blowing from nowhere to nowhere.

Kokerboomkloof, Richtersveld. Note Quiver Trees.

Kokerboomkloof, Richtersveld.

Another journey I would rank high in my hierarchy of ones to be remembered is the trip I made with my sisters and their kids, across the arid, thorny badlands of the Great Karoo and then down the West Coast to the mountain wilderness of the Cedarsberg.

Pakhuis Pass, Cedarberg.

Cedarberg.

Once a vast lake, the Karoo is now a place of extremes, hard and waterless. The early Trekboers who settled here – and those who followed – had of necessity to be tough for it is a harsh, unforgiving part of the world.

The white population has thinned out over the years, as the younger generations has drifted off to the cities. Many of the old farmhouses stand abandoned, there presence demarcated by a few ancient gumtrees, the skeletal remains of a windmill and the rusty wrecks of cars.

This particular trip was to have a spiritual dimension to it. My sister, who was then working on her Ph.D. in Social Anthropology, was keen to visit the Doring River, hoping to find out about the local belief systems, especially those pertaining to water. I volunteered to join her, driving on the dusty road that crosses the Pakhuis pass and then descends through ever drier country down to the river.

Strangely enough, there was a donkey dutifully waiting for us when we arrived on its banks, like he had been ordained as our designated guide. As soon as we got out the bakkie it turned, as if signaling us to follow, and proceeded to lead us down a hoof-pocked track, past fleeting pools that reflected the blue sky above until we came to one large, reed-lined one where it stopped. This, my sister decided, must be the spot.

Leaving her to make contact with the mythical giant snake and the mermaids that might inhabit its depths, I set off to explore the surrounding sun-blasted, cave- riddled cliffs.

On a knoll overlooking the river I came across one that had several faded San paintings on its wall.

Sitting in this ancient cave where, a few hundred-years ago, members of a vanished race of hunter-gatherers also hunched up I could feel the great stillness of this African landscape seeping in to me. A sense of place is often bound up with the history of the people who once lived there so it was saddening to think of the areas former occupants who had been hunted down or driven to even harsher climes.

In a continent the size of Africa you would have expected there would be space for all.

The Little (or Klein) Karoo, which falls mostly on the eastern side of the imposing Swartberg – and which I am much more familiar with – has a similar lonely, sparse, windswept feel. Like its larger neighbour, it is a haunting landscape of low trees, flat plains and ranges of lavender and purple mountains.

Red Hills near Swartberg.

Buffleshoek, Little Karoo.

Back in the times when the Karoo was mostly lake and swamp, millions of reptiles lived and died here leaving their fossilised remains behind in the shale to give the palaeontologists lots to argue about much later. The Karoo is manna to such scientists.

Although I am not from these parts I have always felt a strong connection with this parched and ancient land too. It fills some unarticulated need in my soul.

I get a similar feeing whenever I visit the Langeberg, in the Western Cape, although, in this case, it could be imprinted in my DNA since my Orkney Island ancestors settled here back in 1817 and their descendants still farm the land.

The Richtersveld, Boesmanland, the Hantam Karoo, the Plains of Camdeboo, the Valley of Desolation, the Suurveld, the Langeberg – all have lodged themselves inside me. There is one other place, though, that has prior claim to my heart – the Bushveld. Each time I go there it is like a nostalgic journey in to my past.

Opinions differ as to where it actually begins. Some say it is where you start seeing Marula trees. Others, a particular bird (in my case it’s the White-crested Helmet-shrike). Mostly, it is just an instinctive, gut thing.

Valley of Desolation.

Plains of Camdeboo.

Karoo scenes.

Langeberg, Western Cape.

Marakele, where I also went with my friend Ken, certainly feels like it is in it. The park falls in part of the Waterberg and is dominated by the pyramid-shaped Kransberg. An interesting fact about this mountain is that the architect Gerard Moerdijk, who had a farm nearby, is said to have based the Voortrekker Monument on it. There is also a butterfly that occurs only on this mountain.

You can actually drive to the summit via a narrow, twisting road, the views from which are superb. It is a road you need to go carefully on. We had the harrowing experience of being chased down it, in reverse gear, by an enraged elephant bull. How we didn’t end up, a crumpled wreck, at the bottom of the valley I shall never know.

View from top of Kransberg, Marakele.

Waterberg, Marakele.

When I go seeking the Bushveld, my favourite escape route is, however, the Great North Road although we usually skip the freeway and take the old main road. This way you don’t miss out on the old platteland towns.

If you branch off at Polokwane on to the R521 you follow roughly the same route the Pioneer Column took on its way up to what would become Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). When you reach Vivo, my advice is to take a left turn at the crossroad, taking the road that leads to one of South Africa’s hidden gems, the Blouberg Nature Reserve. If you love plants as well as birds this is the place to for not only do its step mountain slopes contain the biggest colony of nesting Cape Vultures in the country but also probably the widest variety of trees for a reserve of its comparative size.

Blouberg. Vulture colony cliffs. South side of mountain..

Blouberg from North side.

Here, as much as anywhere, you feel you are in the true heart of the Bushveld.

Rejoining the R521 we then usually head north through Alldays to Mapungubwe where an isolated stone-working community once lived amongst the red sandstone cliffs that border the Limpopo river. Their civilisation was linked to trade routes that stretched all the way to the Indian Ocean and beyond. Mapungubwe is now a game reserve but driving through the hot, dry, strangely eroded countryside you still get a fleeting sense of its former inhabitants ghostly presence.

There are many tall, beautifu,l trees along the Limpopo as well, but move a few hundred yards inland and they are replaced by miles and miles of scrubby mopani, that accompany you eastwards all the way to Pafuri and beyond.

But the Kruger, the rest of Limpopo province and Mpumalanga, where I also often go, are a story in themselves, a tale for another time…

Sentenced to no more travel for the duration, it often feels those journeys were undertaken by someone else; or perhaps it is my life in some parallel universe. Longing for beautiful scenery (not that there is anything wrong with the view from my balcony) but unable to take a holiday because of Covid-19, I am forced to do the next best thing. I delve in to my collection of travel books.

I gain a lot of comfort from them. The older I get, the more it occurs to me that I am not going to to be around forever. I no longer have the time to visit a fraction of the places on my bucket list. This is my way of short-circuiting that. Reading about other peoples travels and adventures, is a fun way to live vicariously through them by snooping on journeys you are probably never going to be able to make.

Plus it is a lot cheaper and you don’t have to worry about leaving any carbon footprint…

Thank you for sharing this nostalgic and very evocative essay which puts into words my own feelings and frustrations exactly, possibly because of a shared Melsetter legacy. Also great photos. Best wishes, Graeme

LikeLike

Thanks, Greame. I think it is that Moodie blood of ours!

LikeLike

Evocative and brilliant as always Ant. Oh the nostalgia for those open roads taking us to magical places

LikeLike

I know, Pen. Lets hope you and I can do it again – maybe following in the footsteps of the Moodies or popping in to Kruger!

LikeLike

Hi Ant,

You always nail it. Your intro rings true for so many of us. I think we had enough paternalism and authoritarianism at boarding school and army to last a lifetime. That’s why I enjoyed the joyful loneliness of canoeing some of our amazing rivers (Umkomaas) and road tripping very similar places to you.

Don’t despair, dip into that bucket as I think there is still a lot of steam left in your boiler.

Thanks for a great post.

Hugh

LikeLike

Thanks, Hugh. I think you and I are cut from a similar cloth…

LikeLike

Stidy, what a beautiful piece. You start with such home truths and then delve into the joys of discovering some amazing places, which I have been privileged to discover with you. Such great memories, thank you.

Interestingly, the next big expedition I have my eye on – to Etosha – could well take us back to some of those Northern Cape places on The Great Traverse …

I feel really blessed to have seen such wonderful places … and also an enormous itch to get back into the wilderness!

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Ken. I have also been feeling a bit itchy-footed!

LikeLike