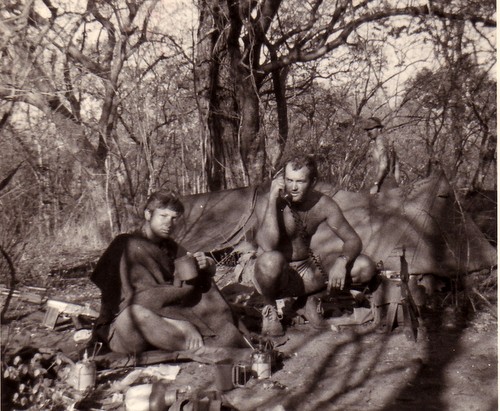

Ignoring warnings that a massive cold front was headed in the same direction I packed my backpack and, full of optimism for the journey ahead, headed south to join a group of equally intrepid hikers who were planning to hike the Mtentu section of South Africa’s iconic Wild Coast. Organised by local adventurers, Ian and Mandy Tyrer, it was a journey I had done the previous year (see Stidy’s Eye) but this time around we had decided to reverse the order – instead of walking from the Wild Coast Sun to Mtentu we would hire a local taxi to Mtentu and walk back from there.

We opted to use the small coastal resort of Trafalgar as our staging post because of its close proximity to our starting point. The next morning we all gathered in the Wild Coast Sun’s underground car park. It was an interesting mix of faces and personalities that milled around, most of them – like me – well past the first flush of youth. They seemed a mellow bunch – not given to postures, prepared to accept what lay ahead. Over the next few days I would get to know them better, the quiet and the talkative, the funny and the serious.

There were two bakkies into which we all squashed, like peas in a pod. Promptly, at seven, we were off, initially on tar and then down a rude dirt track. The road was in an awful state, made even worse by the recent April floods but at least the drivers were considerate edging their vehicles cautiously through the washed-out sections and all the ruts and bumps. It didn’t help. About halfway through the journey, the front vehicle ground to a stuttering halt, plumes of white smoke belching out of its cab. A fan belt had broken. The drivers remained completely unperturbed by this turn of events. Within fifteen minutes they had miraculously conjured up a replacement vehicle, seemingly out of nowhere, and leaving the broken truck parked in someone’s backyard we were off again to our destination, still several hours off.

Our accommodation for the next two nights at Mtentu was a prefab – the Fishin’ Shack – run by the friendly, effervescent Kelly Hein and set amidst a scattering of huts and brick and cement buildings, huddled together as if for mutual protection from the elements, their interiors smoky from cooking fire. On the other side of the sagging fence that marked off our bit of turf, a large hairy black pig snuffled around looking for edible items. An assortment of chickens, dogs, goats, cattle and even a solitary horse also milled about, using the walls and roof overhangs for shelter from the rigours of the climate. The resident old woman shuffled past off to perform her daily chores while a gaggle of kids giggled and chatted and played games with one another. On the top of the hill, alongside, stood the local shebeen from which the occasional burst of drunken hilarity emanated.

I was delighted to be back.

That afternoon, with the sky blackening and curdling around me, my hiking companion and I took a stroll down to the nearby Pebble Beach. Halfway down the hill, a grey cat decided to join us and then, a bit later, changed its mind and wandered back. A dog came bursting out of a yard, yapping its head off. Women with large bundles of wood on their heads strode through fields along slender paths. We carried on down the path to where a brown, brackish sea lapped against a beach littered with storm debris and driftwood and piles of multi-coloured stones scattered across the beach like an assortment of Smarties tossed aside by some rich giant’s spoilt, thoughtless kid.

I had promised my sister I would collect a few of these beautifully smooth pebbles to place on the grave of her much-loved dog who had recently died. I was certainly spoiled for choice. but made a selection, just glad that this time I wouldn’t have to carry them all back (we had arranged with the taxi owners to carry our gear for us).

With the sun – or what we could make out of it – about to go down we hurried back. Huge clouds were beginning to stack themselves in the south.

That night, the predicted rain duly arrived, sheeting down something awful on the corrugated roof under which I lay. There had been no bed available for me inside the shack and so I had made a little home for myself in the corner of the stoep. Sleep was out of the question as I stretched out in my sleeping bag on its cold hard floor with the wind periodically gusting fine sprays of rain onto my face.

Towards dawn, the storm gradually faded away but I could hear the steady pounding of the waves against the rocks on the seashore down below us. In my drowsy state, they sounded like a medieval army on the march. As my consciousness flickered between sleeping and waking, some lines from Matthew Arnold’s On Dover Beach slunk into my head.

Listen! You hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves suck back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence, slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

In this famous poem, the sea symbolises religious faith with the poet acknowledging the diminished standing of Christianity, unable to withstand the rising tide of scientific discovery. The cycle of belief and unbelief. More than that, the poem is about the battle against darkness, something which seemed to me as relevant now as it was back then.

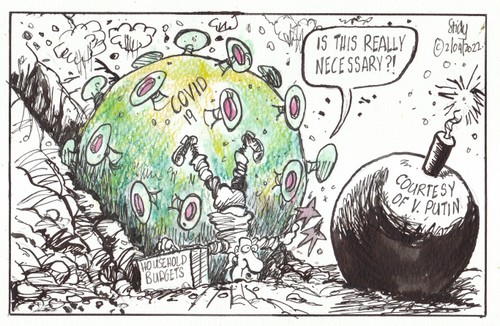

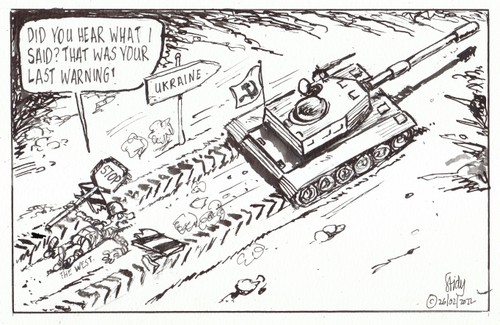

As I watched the rain dripping off the roof, I reworked the poem’s lines through my imagination, adjusting the sentiments to our present time. With war raging in Ukraine, there was little doubt about the nature of these modern demons. Like the poet himself, I was overcome by a sense of sadness at the pointlessness and mass stupidity of it all:

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

But there was no time to brood. It was time to get up. There were lots to explore. Our team leader decided he wanted to check the size of the river we would be crossing the next day so I volunteered to join him.

The sky was full of biliousness, the clouds unable to decide what shape they wanted to be. Out over the sea, wisps of mist were chasing one another. Every now and again the odd squall of rain would hit us but with nothing like the intensity of the night before.

We walked on. The land rolled and sloped away down to the sea with the occasional hunched tree sticking its head above the sun-burnished grass. Scattered over the hillsides were the odd settlements and small groves of Pondo palms. A flock of goats came striding purposefully by, off in search of the day’s grazing, studiously ignoring us as they went. Two black bulls nudged one another in mock combat, trampling the grass underfoot.

The sun was cutting through the cloud and sending golden bars dancing on the sea surface as we made our way down a grass embankment, that was oozing water from all the rain to the fat, curling river. Several cows were grazing along its banks.

With its treacherous currents, hidden reefs and unpredictable weather the Wild Coast has, over the centuries, provided a graveyard for countless ships – and, sure enough, lying on the beach, on the side of the estuary, were the skeletal remains of one such vessel. Some aspiring graffiti artist had painted a skull on its boiler. It seemed an oddly apt metaphor. Good artwork too.

Having satisfied ourselves that the river was fordable, we set off back.

In the afternoon I elected to walk to the viewpoint that provides a panoramic view over the Mtentu Gorge. With cliffs that tower above the river, it is a compelling sight. Just to the left of where we stood a beautifully clear side river tumbled over a series of steps and then fell down into the main river. At the base of the cliff and along the gorge slopes grew a dense mass of vegetation, the trees and bushes crowding together, pressing out over the water to gather the direct and reflected sunlight. In front of them, Mangrove trees stood in the saline shallows. I spotted a pair of Egyptian Geese having a domestic quarrel on a spit of sand way below and then several Trumpeter Hornbill came flapping heavily over the forest canopy, shattering the peace with their extraordinary calling. As if on cue, an Eastern Olive Sunbird piped in with its far more tuneful little melody.

Standing on the edge of the cliff, looking along the river and then out to the choppy sea gave me an extraordinary uplifting feeling, one that immediately banished from my mind the sense of impending doom I had felt earlier on. For me, God is the Great Outdoors and the view certainly made me feel like I had ascended to a loftier plane of being. Here, surely, was the real meaning of holiness?

Back at the Fishin’ Shack, I discovered we had been befriended by a dog. Because of her gentle, trusting, respectful nature, she was immediately dubbed Lady. The owner of the Fishin’Shack asked us if we would mind taking her back to her rightful home – our next stop along the way? Having all developed a deep fondness for the animal, we could hardly refuse.

Lady seemed excited at the prospect of joining us, slotting in happily behind us as we set off the next day. Hiking along a beach like this, you soon settle into a steady rhythm. Behind me, I could hear a steady stream of chatter but I was content to be alone with my own lonely, mystical thoughts. We walked, hour upon hour, along the shoreline with all its shifting moods and then up over roller-coaster hills which led us, eventually, through the strangest of apparitions – a Mars-like, small red desert. For a moment it made me wonder if our host had slipped something into my meal which was now causing me to hallucinate? A desert? Here?

The stark beauty of these dunes could prove their undoing. The reason the sand is so red is that it contains titanium. Loads of the stuff. And several rapacious, international, mining companies are keen to get their hands on it even if it means destroying this undeveloped slice of paradise in the process.

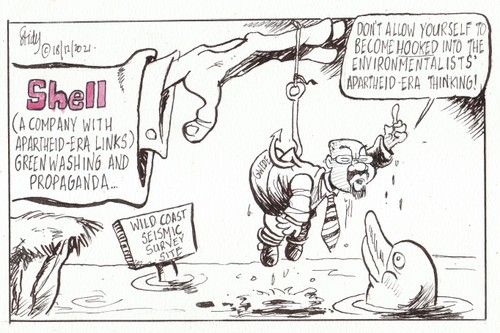

The Pondo, who have lived here for generations and see themselves as stewards of the land, have opposed any attempt to let them do so. Instead of siding with them, which would seem the morally right thing to do, the Government has, in the past, tended to back the mining corporations (just as it recently did with Shell’s plans to carry out seismic surveys off the Wild Coast). When it comes to the exploitation of natural resources and the possibility of making a massive profit, the noble principles on which the ruling party were founded and which were so well articulated by Nelson Mandela seem to have been quickly forgotten.

Once again my thoughts returned to On Dover Beach and the cold evil flooding every corner of the world. Greed.

We trudged on, Lady still trotting uncomplainingly behind us. Eventually, a raggle-taggle of brightly-coloured huts set up on a ridge dotted with strange rock formations and small ravines came into view. This was our final night’s accommodation. Just beyond it, lay the Mnyameni River gorge (with its stunning waterfall) where we would go for sundowners that evening.

We were a little disconcerted to discover, however, that there had been a misunderstanding. This was not Lady’s home. Nor was the owner in a position to adopt her. So a member of the group nobly offered to do just that. Lady, the rural Transkei hound, was now Hilton bound and about to discover a whole new level in healthcare and lifestyle.

My luck was running in the opposite direction. I had begun, by now, to realise I was seriously unwell. Somewhere along the way, I had picked up a chest infection. Feeling poorly, I retired to bed early that night. Unable to sleep, I lay in my tent and looked out into the star-smattered sky, as a bright, luminous moon rose out of the sea, looking like a large tangerine (Where the ebb meets the moon-blanch’d sand – Arnold again). The air smelt slightly wet and tainted with the faintest taste of wood smoke.

The next morning was warm and welcoming with not a cloud in sight as we set out on the final leg of the hike, taking Lady with us. She seemed pleased at the prospect. So did I. Energy levels can rise and flag on a strenuous journey like this but right now – wonky chest notwithstanding – I felt good. In the early morning glow, the countryside looked radiant, and the sea was as wild and dramatic as any romantic painter of scenes such as this could have hoped for. The waves were collapsing and wheezing along the shingle. I was excited to spot a Black Oystercatcher, ferreting around in the rock pools as the sea thundered behind it. Up until then, I had been a little disappointed by how few birds I had seen.

The whole scene was wonderfully free of the crass commercialisation that typifies so much of the South African coastline although there was plenty of that just to the north. I was happy to cling to the illusion there wasn’t.

With the sun growing increasingly hotter in a brilliant blue sky, some of my earlier enthusiasm began, as the waves alongside me, to flow away as we toiled on along the beach. By now my face was as pink as a prawn from my laboured breathing and the physical exertion. There was to be no easy let off. Because of all the rain, we were unable to ford the Mzamba river at its mouth as was the normal custom and were forced to make a long detour inland to another crossing point upstream.

The hike to the top was steep, hot and seemingly endless but eventually, we staggered to the edge of the gorge. Then we plunged down a track that looked like it had been designed by a committee of goats to the river below which we crossed via a suspension bridge. The last few kilometres back to the Wild Coast Sun were sheer hell. My feet ached and thanks to my infected chest, my breath came out in slow, asthmatic gasps. My throat felt like I had accidentally swallowed a roll of sandpaper and it had got stuck there. As I hobbled into the parking area I felt like some ancient pilgrim who had just been forced to pay penance for his sins.

The final stretch…

Judging by my fatigued state, I must have sinned a lot too. As I flopped down, exhausted, I reckoned I had purged the whole lot from my soul.

Inside the parking lot, it was a tender moment watching Lady driving off to her new home where we knew she would be well-loved and taken care of. Then it was our turn to drive out of the gate and I found myself shaken to be plunged back into a tumult of traffic headed north to Durban. After our three day hike, during which we had not encountered another soul on the beach, I found it quite unnerving. What could be more depressingly different than driving down a motorway? I drew comfort, though, that somewhere, far away from the shrieking commotion, lay the healing magic of waves crashing on a deserted shore…

GALLERY:

Seascapes

Village Life

More Village Life

The Passing Scene